IDCE, Geography, Becker School to partner on NSF-funded research

Xochimilco, a municipality in southern Mexico City, contains the last vestiges of indigenous Aztec floating gardens — or chinampas — a farming and transport system. Still producing food today, the centuries-old canal system is shrinking due to climate change and population-induced water scarcity, and has become polluted due to tourism. (Mexico photos courtesy of Ravi Hanumantha)

Researchers from Clark University are embarking on a three-year project in Central Mexico that, for the first time, will meld GIS mapping, system dynamics modeling, extended reality (XR) technology, and new educational experiences, to help policymakers and the public collectively understand how much is at stake under climate change.

“As scientists and educators, we need to work creatively and collectively to help the public and policymakers understand,” says Tim Downs, associate professor in Clark’s Department of International Development, Community, and Environment (IDCE) and the grant’s principal investigator.

Through the project’s co-creation model — where academic researchers collaborate with government and community stakeholders, including indigenous populations — “we have the ability to explore alternative climate and development scenarios of the future,” Downs explains. “As our baseline, we can explore what a business-as-usual trajectory would look like — one where we keep using fossil fuels at the same rate, and we have an incremental approach to climate adaptation.”

Funded by a $1.5 million grant from the National Science Foundation’s Partnerships for International Research and Education (PIRE) Program, the project, “Co-Creating Research and Education Capacities to Understand, Visualize, and Mitigate Climate-Change Impact Cascades and Inequities in Central Mexico,” will involve nine faculty and 19 graduate students from Clark’s IDCE department, Graduate School of Geography, and Becker School of Design & Technology.

They will collaborate with their peers at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), one of the top public research universities in Latin America with nearly 370,000 students. Joining the project will be UNAM’s Marisa Mazari-Hiriart, a senior researcher in the National Laboratory of Sustainability Sciences (LANCIS); Paola García-Meneses (LANCIS); Francisco Estrada-Porrua of the Climate Change Research Program (PINCC); and Julián Velasco-Vinasco at the Institute of Atmospheric Science and Climate Change (ICAyCC). Downs and Mazari-Hiriart are both doctoral alumni of the Environmental Science & Engineering Program at the University of California, Los Angeles, and began working together 25 years ago on water sustainability solutions for Mexico City.

Mexico City’s water crisis: a barometer for climate change

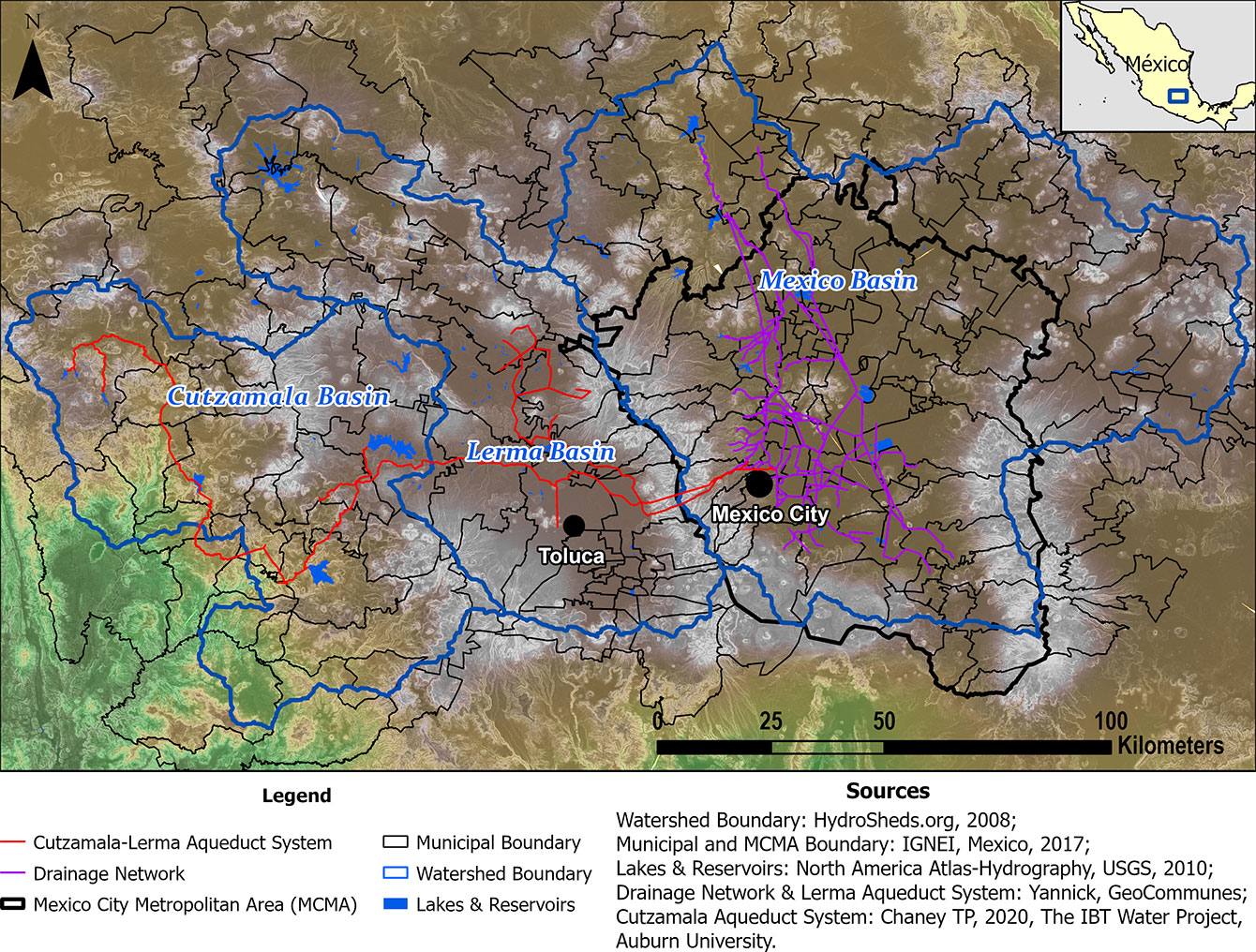

The project focuses on the Mexico-Lerma-Cutzamala Hydrological Region (MLCHR), which provides water to 26.8 million people, across 200 metropolitan communities, from urban to rural areas (see map). With a longstanding water crisis and drought conditions, Mexico City — the fifth most-populous city in the world — has become a barometer for the impacts of climate change.

“In our research, we’re entering this complex world of climate impacts through the gateway of water, and what’s happening to water, because water is life. Water is fundamental to everything,” Downs says. “This region is emblematic of the types of hypercomplex challenges that the world is beginning to face more and more.”

According to Downs, impacts to water affect many areas: agriculture and food; aquatic ecosystems; and human health and livelihoods. These “impact cascades” are unevenly distributed across landscapes and populations, resulting in inequities. The combination of GIS/geospatial analysis with system dynamics modeling — done in collaboration with partners — will enable the researchers to illuminate this complexity and create a shared understanding, he says.

By drilling deeper for water underground, Mexico City has destabilized the ground, and the city itself is sinking into the compressible lake beds of the volcanic basin. Even with a vast aqueduct snaking through the region to supplement supply (see map), the local groundwater is drying up; the city is pumping more and more water from neighboring watersheds in the far west, with plans to triple such transfers by 2050. This practice raises major environmental and water-justice questions in an unstable, climate-changing world, Downs says. The project seeks to understand these implications — both now and under different future development and climate scenarios — to anticipate and mitigate them, and to promote sustainable, climate-resilient, socially just alternatives.

Map of the Mexico-Lerma-Cutzamala Hydrological Region

“We’re studying this region because it’s an example of what’s wrong with ‘business-as-usual’ development. The Mexico City basin has been overexploited for 50 years,” says Downs, an environmental scientist and engineer with expertise in aquifers and watershed stewardship. “There are all of these pressing environmental and social justice questions – and it all gets even more urgent under climate change. However, unless we do the work, we don’t really know what is at stake or how to act.”

Water scarcity in a climate-changing, rapidly urbanizing world is burgeoning. By 2050, two-thirds of the world’s population is projected to live in urban areas like Mexico City. That will include millions of climate refugees, many of them indigenous, from rural regions left uninhabitable by water and food insecurity, and other conspiring factors like heatwaves, forest fires, and flash-flooding.

In an Applied Geography article, IDCE-UNAM researchers describe how urban land cover has grown by 82 percent in the MLCHR over 25 years. In a chapter of the recent book, Handbook of Human and Planetary Health, the researchers use the project to illustrate the need for a new approach to understanding and addressing complex intersections among climate, water, food, livelihoods, social justice, and health — by designing and deploying integrative, co-creative projects.

Using technology to visualize, inhabit alternative futures

The researchers will work closely with local communities and policy makers — including the Mexico City government — to create a shared understanding of existing and historical climate, environmental, and social conditions. Yelena Ogneva-Himmelberger in IDCE and Abby Frazier, Karen Frey, and Rinku Roy Chowdhury in Geography, and graduate students will collaborate with partners in Mexico to develop a web-based regional climate-change atlas.

Cynthia Caron, associate professor in IDCE, will contribute her expertise in natural resource governance and gender inequity, and Morgan Ruelle, assistant professor in IDCE, brings a background in working with indigenous communities and place-based knowledge to confront climate change. A Ph.D. student, Ravi Hanumantha, has worked with the team to conduct preliminary research for the project, and will continue for another year.

The Becker School of Design & Technology’s involvement in the project adds another dimension — literally. When Downs learned about the BSDT faculty’s renowned expertise in extended reality (XR), “it was a lightbulb moment: Wouldn’t it be cool to use XR for exploring and virtually inhabiting alternative futures to help people anticipate what things might look like under different scenarios, in a way that, up to now, has not been possible? It could transform the way we make decisions as a society.”

When presented with two-dimensional maps, BSDT Professor Terrasa Ulm and Dean Paul Cotnoir immediately imagined other ways to share information with “people who aren’t in the numbers game of climate and global change,” Ulm says. “The idea is, how do we make that more immersive? Extended reality cuts you off from everything else. You’re fully embodied in the experience.”

The regional climate change atlas and system dynamics modeling will work together to provide inputs to the XR simulations. “It’s not like we’re going to provide the data,” Cotnoir adds. “We’re going to take them and put them in a format that is much more impactful to a larger group of people.”

The XR experience would be built for government officials and community members in Mexico to visualize alternative futures based on the policy decisions they might make, Ulm emphasizes.

“This is really key to us. We don’t always want this to be a negative outcome that is happening; you also need to be convinced of a positive outcome if you make changes,” she says. “It’s about trying to adjust some of the data that would be changed by policy and seeing the positive and negative potentials.”

As part of the project’s focus on innovative education, a planned interdisciplinary course would allow a team of graduate students in BSDT, IDCE, and Geography to apply the full range of skills — artistic, audio, technical, research, community development, and GIS — required to create an XR application. Undergraduate students in the Interactive Media Program’s Game Studio and Serious Game Project course also would be involved along the way.

For Ulm, the project could be a testing ground for how interactive media designers might work closely with researchers, communities, and policymakers to make accessible the huge amounts of data that have been generated over the years.

“Tons of data are being collected in all areas, across all disciplines, and they need new ways to be visualized to make them more accessible to audiences outside the expert areas or even in those expert areas,” she says. “How do you make that meaningful and interact with the data on a human level?”

Graduate students living and studying in Mexico

Three cohorts of graduate students from BSDT, IDCE, and Geography will play a fundamental, enabling role in the project, working with community members, government officials, and their peers and researchers at UNAM. The project will fund 19 graduate students at Clark over three years.

Over the past few years, IDCE graduate students have collaborated with Downs, Ruelle and Ogneva-Himmelberger to lay the groundwork for the project. Ruelle credits these students — many of whom served in the Peace Corps and received Clark’s Paul D. Coverdell Fellowship — “for urging us to allow students to develop deep relationships with the community.”

In spring and summer 2024, the first of three cohorts of seven Clark graduate students will live in communities in Central Mexico, study, and conduct research with their UNAM peers. In the spring semester, the Clark field cohort and their UNAM peers will be joined by other Clark students remotely in two hybrid courses taught by Downs, who will be based at UNAM.

“The emphasis is on collaborative research-based learning, so we want Clark and UNAM peers to work together and take courses together taught by Clark and UNAM faculty. Education and learning innovations, in synergy with research and practice, are a major component of the project,” Downs says.

“We are also going to be working with local middle and high school students, and their teachers, using 3D-printers to make climate monitoring stations, deploying them, gathering data, then making sense of them — energizing their learning,” he adds. “Youth, after all, have the biggest stake in the future.”

Typically, when researchers arrive in a community, they first reach out to other academics and government experts, Ruelle acknowledges.

“You then find that there are other people who live close to the environment and on the land,” says Ruelle, who has worked with indigenous groups as part of his study of agroecological systems. “In a lot of these communities, there is a history of extractive research, where knowledge is accumulated and filed away in a report. We’re working against that history.”

Downs is especially excited by the interdisciplinary, integrative, co-creative approach to the research and education, which he and others plan to continue beyond the three-year grant.

“This is my dream project,” he says. “I remember coming to Clark [in 2001] and joining IDCE in the early days and seeing the potential to do this kind of work.”

Clark’s Graduate School of Geography is hosting a special celebration of its 100 years as a transformational force in geography, April 13–15. Learn more about the centennial event and how to register for the luncheon, dinner, and receptions.

Project seeks graduate students for funded positions

Clark University’s climate change project with the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) in Central Mexico will fund 19 graduate students at Clark over three years.

Faculty are seeking fluent — preferably native — Spanish speakers to apply to six degree programs, including the:

- M.S. in Environmental Science and Policy

- M.S. in Geographic Information Science

- M.A. in International Development

- M.A. in Community Development and Planning

- Master of Fine Arts in Interactive Media

- Ph.D. in Geography

Professors Yelena Ogneva-Himmelberger, Tim Downs, and Morgan Ruelle stroll in front of the Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral, which had been sinking and in danger of collapse until it was saved by major remedial engineering. Like many structures in Mexico City, the sinking was caused by the over-exploitation of the aquifer, leading to the differential settlement of the cathedral’s foundation.

IDCE researchers at UNAM’s famous Central University City Campus, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, which features murals by Juan O’Gorman, Diego Rivera, and other artists.