Robert Tobin, Henry J. Leir Chair in Language, Literature and Culture at Clark University, recently returned from several weeks in Berlin, where he started a new book project, researching the connection between human rights and sexuality. He also met two Clark students traveling to Europe as part of their undergraduate research, and he connected with fellow academics, laying the groundwork for additional publications and presentations.

Tobin’s trip could not have been better timed for someone who has traveled to Berlin and witnessed political change in Germany since before the fall of the Berlin Wall.

On June 23, “I arrived the day that Britain voted to leave the European Union (Brexit),” he says. “In my humble opinion, I think the EU will survive this, and Germany will actually have a stronger role to play within the EU. …

“I was also interested to see the effects of the influx of a million refugees into Germany (80,000 into Berlin) alone. Despite the adjustment problems and inevitable backlash, I think Chancelor Angela Merkel is right when she says, “Wir schaffen das” (We can do this!).”

Below, in a blog post, Tobin writes about his experience conducting research in Berlin this summer.

Delving into the origins of human rights and sexuality

Having just completed a book on the emergence of modern vocabularies of sexuality in German-speaking central Europe (“Peripheral Desires: The German Discovery of Sex”), I am embarking on a new project researching the connection between human rights and sexuality. Whereas many people assume that human rights have only recently focused on sexuality, I believe that sexual rights have been central to discussions of human rights since the origins of both concepts in the 18th century.

Uncovering a journal of human rights

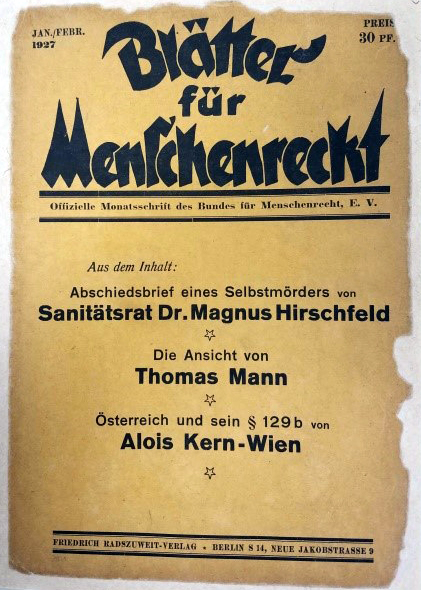

A central chapter in my next book will focus on the Blätter für Menschenrecht(Journal of Human Rights), which appeared monthly in Berlin from 1923 until the Nazis shut it down in 1933. The title of the journal sounds general and all-encompassing, but in fact the journal deals exclusively with the rights of what it calls “homosexual human beings,” whose behavior was criminalized by laws against lewd behavior.

My central question is why did homosexual activists alight upon the vocabulary of “human rights” to argue for their rights?

As Harvard’s Samuel Moyn (who spoke on human rights and the Holocaust at Clark last fall) has pointed out, the term was not all that frequently used prior to the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948.

So why would a popular journal focused on homosexual rights from Germany’s Weimar Republic be called “the journal of human rights”?

The journal had a remarkably large circulation — the editor, Friedrich Radszuweit, claimed that some of his issues sold over 50,000 copies. According to Radszuweit, the Blätter, along with sibling publications, Die Insel (The Island) and Freundschaftsblatt (Journal of Friendship), had a total circulation of over 5 million copies in 1926. Despite their wide circulation, these journals are now extraordinarily rare and available only in a handful of archives. They were not collected by libraries at the time because of their focus on homosexuality. Ephemeral in any case, they suffered especially drastically due to the Nazi persecution of homosexuals.

The German national library, called the Staatsbibliothek, owns only the issues of the Blätter from 1927. But these issues have been gloriously restored.

This story is part of our 7 Continents, 1 Summer series, which highlights the interesting work that Clark students, faculty, alumni and staff are doing all over the world. Have a great story of your own to share? Let us know and we’ll be in touch.

Discovering personal stories from the past

I was thrilled to see the topics on the front page of the first issue. The famous sexologist and activist Magnus Hirschfeld gave an account of a homosexual man’s suicide. The man had actually met Hirschfeld 20 years earlier. His father, a progressive man, had taken him to Hirschfeld when he came out. After receiving counseling from Hirschfeld, the father had blessed the young man’s relationship.

The man went into the army during World War I, serving as a nurse, as many homosexual men did. But after the war, things started to fall apart. The relationship ended. He entered into a new one, but societal attitudes meant that the two constantly faced discrimination and persecution. His father, who had been so supportive, passed away, and the rest of the family rejected him because of his sexuality. The article provided evidence for the deleterious consequences of the denial of rights to homosexual human beings.

I was delighted to see an article in the journal about the Nobel-Prize-winning author Thomas Mann, specifically about an essay he had written in 1925 called “Über die Ehe” (On Marriage).

Thomas Mann himself had homosexual inclinations, but was married and had six children with his wife. In the essay, he argues that, while male-male relationships may indeed be beautiful, the responsible thing to do is get married and have children.

The author of this essay in the Blätter argues that male-male relationships are not based on beauty alone, but also on a sense of responsibility to each other and society. He points out, moreover, that the rights of heterosexual couples are fully recognized, even when they do not have children. One of the interesting discoveries that I’ve made is how early many of these activists understood marriage as a matter of equal rights.

These articles were exciting. However, I’m still looking for a direct statement explaining the movement’s use of the terminology of human rights. How did these men and women in the 1920s understand the concept of “human rights” in such a way that it also included sexual rights, specifically the right to be gay or lesbian?

I’m also still looking for more issues of the journal. The library of the Humboldt University in Berlin supposedly has more issues of the journal. However, when I requested them, the library was unable to find the copies that they own. An example of the frustrations of archival research!

Berlin’s gay scene: then and now

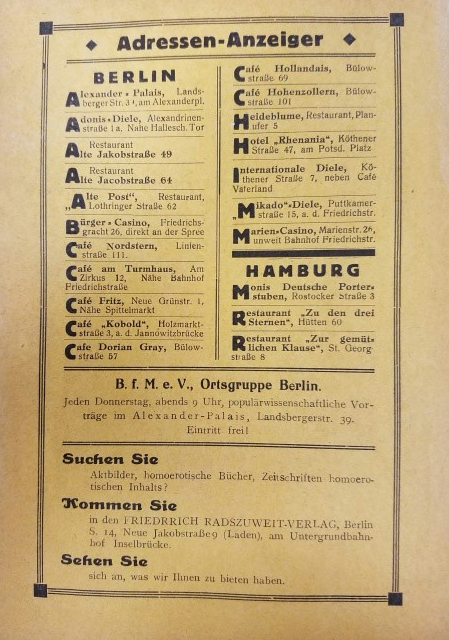

On the reverse side of one of the issues of the Blätter was a fun discovery: a list of addresses of bars, restaurants and cafés that would interest the readers of the journal, essentially a list of places where gay men and women could meet and socialize. Many had charming names that hinted at their nature: “Adonis-Diele,” “Café Fritz” or “Café Dorian Gray.” Many of them are in neighborhoods that are still gay. It’s remarkable to think, for instance, that the Nollendorfplatz area, where Christopher Isherwood lived when he was writing the stories that would become the musical “Cabaret,” was gay over a century ago.

Nowadays, Berlin has one of the most highly developed LGBTQ communities in the world, with an extensive network of cafés, restaurants, bars and dance venues, as well as gay publications, bookstores clubs and political organizations. It also has an elaborate set of gay and lesbian academic institutions, such as the Bundesstiftung Magnus Hirschfeld (the Magnus Hirschfeld National Endowment), which supports gay and lesbian projects; the Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft (the Magnus Hirschfeld Society), which supports research on the history of sexuality; and the Forschungsstelle Kulturgeschichte der Homosexualität, the research center on the cultural history of sexuality at the Humboldt University.

Connecting with colleagues

At a release party for a new scholarly yearbook devoted to sexuality, Jahrbuch Sexualitäten, I ran into Jan Feddersen, an old friend who is a prominent journalist at the leftist German newspaper, die taz, and one of the one of the founding board members of the new yearbook. Later we met to discuss possibilities to contribute to the new publication, possibly with a contribution related to my research on sexuality and human rights.

I also spoke with representatives from Berlin’s extraordinary gay museum, called the Schwules Museum. Afterward, I met with them at the museum and made preliminary plans for a talk, possibly in connection with an upcoming exhibition about the founder of art history, Johann Joachim Winckelmann. While there, I got a tour of their fantastic archives, where I definitely intend to do some research in the future.

I went to the release party with the journalist and academic Peter Rehberg (who spoke at Clark on Bruce LaBruce’s film, “Raspberry Reich,” in the spring of 2015). We discussed the possibility of working together on Rashid Al-Daif’s and Joachim Helfer’s “What Makes a Man? Sex Talk in Beirut and Berlin,” which explores attitudes toward homosexuality in Germany and the Middle East.

While in Berlin, I got the chance to meet with several other people, including the incomparable Rosa von Praunheim, whose controversial film, “Nicht der Homosexuelle ist pervers, sondern die Situation, in der er lebt” (It’s not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, but the Situation in Which He Lives) helped kick off the modern German gay rights movement in 1971. Rosa is finalizing a proposal for a new film, Männerfreundschaften: Homoerotik in der deutschen Klassik (Male Friendship: Homoeroticism in German Classicism), which is in part based on the findings in my book, “Warm Brothers: Queer Theory and the Age of Goethe” (2000).

MEETING Clark students in Berlin

Meghan Paradis, left, and Aviv Hilbig-Bokaer. Both

conducted research in Europe this summer.

In addition to the established scholars and academics with whom I met in Berlin, I also had the chance to connect with two of my students who were conducting independent research there.

Meghan Paradis has been working on topics closely related to my own since she took my class, “The German Discovery of Sex,” in spring 2015. In that class, she wrote a paper, “Shifting Understandings of Lesbianism in Imperial and Weimar Germany,” which appeared in Clark’s Scholarly Undergraduate Research Journal (SURJ). With the help of Clark’s Steinbrecher Fellowship, she’s now continuing her work reading Die Freundin, a 1920s periodical for lesbians published by Friedrich Radszuweit, the same man who published the Blätter für Menschenrecht, which I’m studying.

I also got to meet with Aviv Hilbig-Bokaer, whose essay, “Inhabiting the Discourses of Belonging: Franz Kafka and Yoko Tawada,” came out of my class, “Germans, Jews and Turks,” and also appeared in SURJ. He had just completed a trip to Russia, where he had traveled with the help of a LEEP (Liberal Education and Effective Practice) grant. Through his research, he sought to understand the great classics of Russian literature more deeply.

Speaking of students, I also got a chance during this trip to visit the campus of our study abroad program, CIEE Berlin. Both Meghan and Aviv had been studying there in the spring, along with a large number of other Clark students.

I also had an interesting opportunity to sit in on and observe a class at the Freie Universität, taught by my colleague, Professor Dr. Claudia Albert. It’s always interesting to see the similarities and differences between students in Germany and in the United States.

A ‘deeply moving’ trip

Overall, this was a productive trip that was also deeply moving. I’ve been going to Berlin since 1982, before the Berlin Wall fell. It has been breathtaking to see how this city has grown in the last quarter century. Historic buildings have been restored, stunning new ones have been erected. The gay community has thrived and the city as a whole has become more diverse and exciting than ever before.