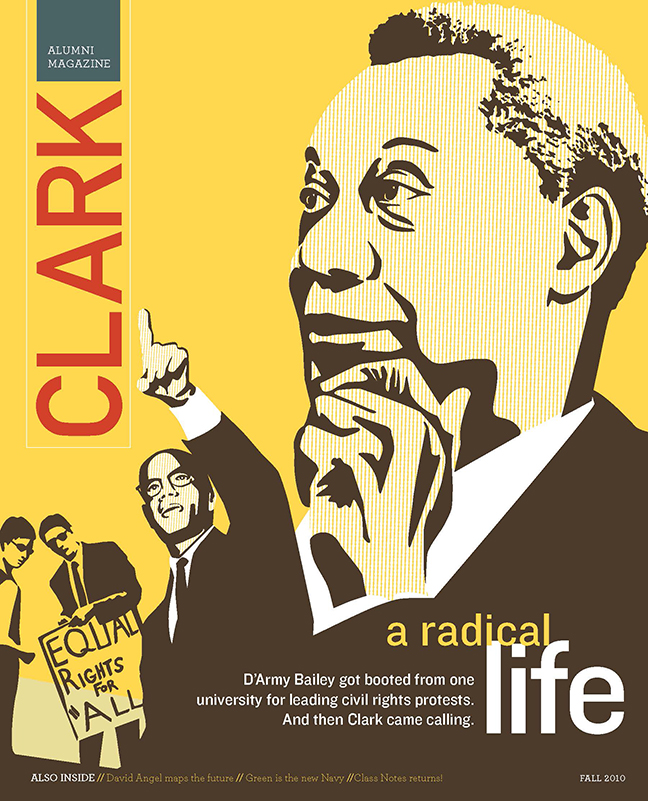

D’Army Bailey ’65: A Radical Life

D’Army Bailey was not born with an apostrophe in his name.

That came later. In the summer between eleventh and twelfth grades, he decided the way most folks pronounced his birth name of “Darmy” was too pedestrian — Didn’t they realize there was supposed to be a slight pause between the “D” and the “A”? — and that the collection of letters by which he’d be known throughout his life needed something to distinguish itself. So he adopted the apostrophe.

The sideways wink of punctuation may have set him apart early in life, but D’Army Bailey wouldn’t need it to get noticed later on. His name found its way into newspaper headlines and police reports, into movie credits and legal decisions, and onto the cover page of a thick FBI file that labeled him a “subversive.”

The civil rights movement found him at Southern University in Louisiana, the largest all-black university in the country, where he discovered a streak of discontent among his fellow students that turned him from dispassionate observer to hesitant participant, and finally to a key leader of protests that spilled off the campus and onto the streets of Baton Rouge.

The civil rights movement followed Bailey two years later to Clark University, where students raised scholarship money to bring him to campus after he was expelled from Southern for his inability to adjust, a gentle euphemism for “making trouble.” In Worcester, Clark’s newest undergraduate, class of ’65, found a different kind of racism — less overtly hostile, quietly institutional, but no less insidious. He took to the streets there, too, enlisting University students to protest the hiring practices of some of the city’s best-known companies while forging connections with everyone from Malcolm X to Abbie Hoffman.

The civil rights movement ensured that D’Army Bailey would make a permanent impression no matter how his name was spelled. In retrospect, inserting that apostrophe was simply the first subversive act of many.

◊◊◊◊

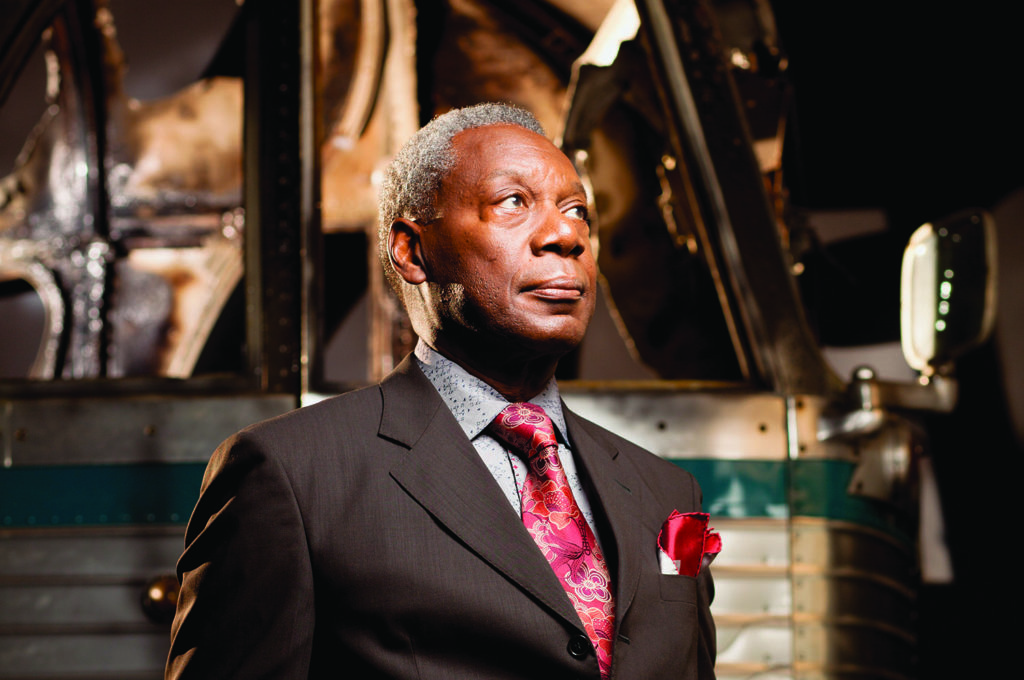

It’s post-ceremony on Commencement Day 2010, and D’Army Bailey is a couple of hours removed from receiving an honorary degree from President John Bassett. He strides across the quad toward a waiting photographer, his charcoal-gray pinstriped jacket slung casually over his shoulder, revealing a blazing white shirt with a pink-patterned tie — his ensemble is surprisingly unwrinkled and crisply creased, despite the steamy temperatures. The crowd has dissolved into small groups of family and friends trading hugs, but mothers and grandfathers and uncles peel away to stop the distinguished man who passes by. They offer their congratulations for the honor he’s just received and for the life he’s led. He treats each interruption with grace, thanking each well-wisher with a handshake and a wide smile.

“I remember walking these same paths more than 40 years ago, engaged in conversations with other students,” he reflects. “The students who brought me to Clark meant well, but they thought that the important gesture of bringing me up here was their way of showing empathy. My job was to take them a stage further. Yes, they made a gesture, but now they had to do more. Otherwise, I would not have felt true to my own beliefs. I felt I was put here for a reason: carry the message up north.”

When he embarked on his college career in the fall of 1959, Bailey carried nothing more than a suitcase, a box of his mother’s fried chicken, and a stern warning from his parents not to get off the train in any of the small towns along the route from his hometown of Memphis to Southern University. “There’s no sense looking for trouble,” his mother cautioned.

There hadn’t been much trouble in Memphis. Like most other southern cities, Memphis was segregated by race in just about every essential area — from schools to buses, housing to restaurants — but the black neighborhoods were tightly knit enclaves with their own social and commercial structures. In the nurturing neighborhoods of his youth, children “were able to endure and grow and not feel emotionally distressed or debilitated from an apartheid system.”

Bailey kept himself informed about the racial struggles occurring throughout the South by sitting in the local pharmacy and reading black newspapers and magazines, which taught him about Emmett Till, the black teenager who was lynched for whistling at a white woman. On the small black-and-white television in his house he watched the reports detailing the court-ordered integration of Central High School in 1957, the National Guard escorting nine African-American children through the angry taunting mobs to reach the doorway.

“As a young black kid, seeing this, you instantly realize you are no longer a kid. You’re an adult, in an adult world, facing adult issues and adult biases and prejudices and adult oppression,” he says. “You also see that these kids at Central High School summoned up the courage of adults.”

His father, a huge baseball fan, had brought D’Army and his brother Walter to St. Louis to see the Dodgers’ Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella play against the Cardinals. African-Americans also were making inroads in other sports like boxing.

Young D’Army was no athlete, but he was a gifted wordsmith who wrote a column for his high school and college newspapers.

“I always felt that you had to take advantage of every opportunity to propagandize, to communicate, to carry forth the message. My Remington typewriter was my basketball — it was a powerful weapon, more powerful than being able to dribble. I still can’t dribble a basketball, but I could get on my typewriter and I could write and express ideas and get those into the black newspapers.”

At Southern, Bailey was studious and resolute about getting himself a good education. He was elected president of his freshman class, wrote his column, played ping-pong in the student union and flirted with pretty girls. Life was good.

Then, on February 8, 1960, four black college students sat down at the whites-only lunch counter of a Woolworth’s store in Greensboro, N.C., where they refused to leave after they were denied service. This action of quiet rebellion ignited similar student movements across the country, including in Baton Rouge, just beyond the gates of Southern University.

Bailey traces his personal evolution from student to student-activist to a time when he saw his campus leave behind its reputation as “a safe, paternal plantation.” It had become a place where the students decried not just racial injustice, but also their betrayal by the school administration who, under pressure from the state of Louisiana, brought police onto campus and expelled protest leaders — anything to quell Southern’s increasingly stormy seas.

By December of his junior year, Bailey was restless and impatient at the sluggish progress of the movement. “It reminds me of a quote: Would you ask a mother whose baby was caught in a raging fire to gradually remove her child from the flames? Radical action is about agitation, agitation, agitation, which is required to bring about change.”

So Bailey agitated — at sit-ins and rallies, and in meetings with stubborn school administrators. On Dec. 15, 1961, he helped lead 2,000 students to the Baton Rouge jail to protest the arrests of Southern students at downtown whites-only lunch counters. They were greeted by the city’s police force, armed with tear gas canisters and snarling German shepherds straining at their leashes.

In his memoir, The Education of a Black Radical, Bailey describes the ensuing confrontation:

“We shall overcome. I fought an overwhelming desire to hit them, slap them, or scream them into realizing we were all the same.

We shall overcome. I fought a deep, gut-wrenching need to run.

Deep in my heart… I breathed deeply.

I do believe… We will stand peacefully. We will stand here peacefully until they let us go forward.

We shall…

They began shooting tear gas. When I turned, the group behind us had already started running.”

Some of the students were arrested during the melee, and were later expelled by Southern University President Felton G. Clark. An enraged Bailey and other student leaders organized a boycott of classes that forced the school to shut its doors ahead of the scheduled Christmas break.

When he returned after the holidays, Bailey was summoned to the dean of students’ office. He was handed a letter informing him he’d been expelled under a vague statute that was normally cited for the expulsion of homosexuals, but which in its three simple words gave the administration vast discretion: Failure to adjust.

Bailey writes in his memoir:

“Perfect. I hadn’t broken any university law, but I hadn’t adjusted to the system. Evidently, the unwritten laws — the ones they don’t mention at freshman orientation — said my thinking was supposed to adjust to the university, along with my politics and my outlook on the world. Since I remained an individual, mine didn’t. As a result, the system threw me out in an act of self-preservation.”

◊◊◊◊

Bailey is accustomed to having his photo taken. His posture, his facial expressions, his lack of inhibition in the middle of a crowd all speak to an instinctual comfort around a camera. When asked to pass through Clark’s gates during a photo session and pose on Main Street, he does so gladly, leaning casually on an iron railing as hip-hop music booms from passing cars.

He tells the story about the time he played a judge in the film “The People vs. Larry Flynt,” one of several acting roles on his résumé. Director Milos Forman had advised Bailey to conduct the courtroom just as he would in real life. So when actor Woody Harrelson, playing the eccentric pornographer, was wheeled onto the set wearing a football helmet, Bailey objected.

“I said, ‘You’re going to have to take that off your head. You can’t wear any hats or helmets in a courtroom.’ He turned his head and started pulling on the helmet strap, but he couldn’t get it loose. So then he finally looked around at the crew with this sheepish expression on his face and said, ‘Props!’”

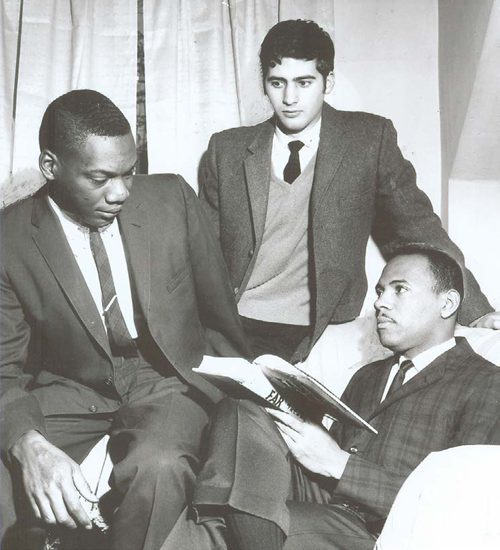

Bailey’s personal situation was hardly unique. In 1962, hundreds of student leaders were being expelled from southern black colleges at the urging of white legislators intent on squashing the protests. At Clark University, a group of sympathetic students launched a scholarship fund campaign, holding car washes, bake sales and other benefit events to raise $2,500 — with a matching sum from Clark — to bring one of these ousted students to campus.

Initially, a student from Jackson State University was offered the scholarship, but he opted to join the military and recommended that his friend D’Army instead be the beneficiary. When he learned of the offer, Bailey was unsure how to respond. The Northeast was like a foreign country to the life-long southerner, and he couldn’t even pronounce the name of the city he’d be heading to (“I thought it was ‘Wor-kester,’ he laughs).

Clark University was an even bigger mystery. He’d never heard of it.

“The catalog did nothing to allay my fears,” Bailey recalls. “How could it? It wasn’t written for me. It was full of pictures of smiling white kids lounging under trees, playing in the snow, and holding beakers and test tubes.”

Despite his reservations, he filled out the required paperwork and sent it off. Within days, the exiled D’Army Bailey was officially a Clarkie.

Upon his arrival in September of 1962, the locals regarded him as something of an oddity, an exotic creature to be scrutinized. A story in the Worcester Evening Gazette began: “D’Army Bailey, 20, should be able to get an A on any examination which asks: How to stage a sit-in demonstration, form a picket line, set up a mass rally — or how to get expelled from college for doing so.”

Still, the University was welcoming, and the weather was less harsh than Bailey had anticipated (he’d bought cleats at an Army surplus store to help negotiate the snow and ice). His first semester coincided with the momentous event of a black man, James Meredith, enrolling at all-white University of Mississippi, which set off riots on that campus. Clark students soon sought out Bailey for his insights on all things racial, southern, and the intersection of the two. (Agreement was hardly universal. When Bailey helped arrange a student bus trip to a University of Massachusetts-Amherst rally in support of Meredith, other students lay down in front of the bus in protest.)

Bailey was happy to answer the questions, but he grew impatient. He felt the students’ compassion veered perilously toward condescension.

“They wanted to hear about all the bigots in the South so they could congratulate themselves on being different,” he says.

“I went along with it all, and I was friendly because they were friendly. Consequently, for a long time, I never felt like me. I was a composite, a representative, a living newsreel — not a person. To these students — most of them from upper-middle-class white communities — I was ‘Negro America,’ a curiosity, and therefore conveniently interesting.”

Yes, the events occurring in the South were important, but what of the racism in Clark’s own back yard of Worcester? Bailey looked around his new city and saw old ways: blacks were largely relegated to service jobs and manual labor; few were elevated to management positions.

Bailey knew that for Clark students to really appreciate the churn of the civil rights movement, they could no longer take notes on the sidelines. They had to join the fray.

He formed the Worcester Student Movement and brought James Meredith and Malcolm X onto the Clark campus to speak. He led student pickets of two venerable Worcester companies — Denholm & McKay, the city’s oldest department store, and Wyman-Gordon Company, a manufacturing giant and defense contractor — to demand that they hire and promote more blacks to managerial positions. When the owner of Wyman-Gordon spoke at a Worcester Area Council of Churches gathering, they picketed that, too. Among those joining the Clark contingent was Abbie Hoffman, whose anti-government activism with the Yippie movement of the late ‘60s — not to mention his wild mane of hair, his American flag shirt, and an aggressive media savvy — would turn him into a counter-culture icon.

“If you had taken the white kids at Clark and put them in Baton Rouge, they would have been in the front lines, perhaps not as ready for the vehemence of the southern reaction, but with the same spirit,” Bailey says. “We all were one in having within us a deep anger at injustice.”

◊◊◊◊

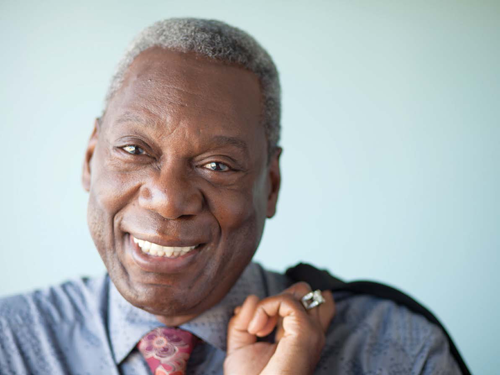

The photo shoot completed, Bailey makes his way back across campus to John Bassett’s house, where his family is waiting. The subject of his FBI file is brought up, and it’s clearly a topic he relishes.

The file was launched during his freshman year at Southern and was added to during his time at Clark and right up through 1973 after he’d gone on to a law career. He learned of the file’s existence a couple of years later from his nephew who worked in Washington, D.C.

“I wrote to the FBI under the Freedom of Information Act in about 1976 or ’77; it took a year to get the file. There were two volumes, each over an inch thick. … They actually began an investigation on me when Lyndon Johnson came to Worcester to speak. I did a radio interview with Huey Newton and the entire transcript was in my files.

“They had two labels for me. The first was ‘D’Army Bailey: Subversive.’ Later they changed it to ‘D’Army Bailey: Black Nationalist Militant.’”

Even after graduating from Clark, D’Army Bailey never stopped agitating. He earned his law degree at Yale, practiced law in San Francisco and was elected to the City Council in 1971. He was later recalled in a special election after pushing hard — too hard, his detractors argued — for affirmative action policies because of the low level of employment for blacks in Berkeley.

Bailey returned to Memphis to practice law and eventually served 19 years as an elected judge on the Tennessee trial court bench. For nine years he spearheaded the successful effort to transform the Lorraine Motel in Memphis — the site of Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination — into the National Civil Rights Museum.

He now practices law in Memphis for Wilkes and McHugh, a private firm that specializes in civil ligation against nursing homes accused of negligent care. Ending his career on the bench, he says, wasn’t an option.

“The notion of being a permanent civil servant going into retirement didn’t suit me well,” Bailey says. “I wanted something a little more challenging.”

To this day he’ll gladly answer to any of the labels he was tagged with during the years he fought for racial justice all the way from Baton Rouge to Worcester. Radical. Subversive. Rabble-rouser. They all fit.

D’Army is just fine, too, so long as it’s pronounced correctly.

Editor’s note: D’Army Bailey passed away on July 12, 2015. Clark University created the D’Army Bailey ’65 Diversity Fund in his honor in 2017, to support initiatives and academic endeavors that advance and help sustain an inclusive, engaged campus.