Clarkives

Lindbergh’s visit, memorable rope pulls, and a must-read newspaper

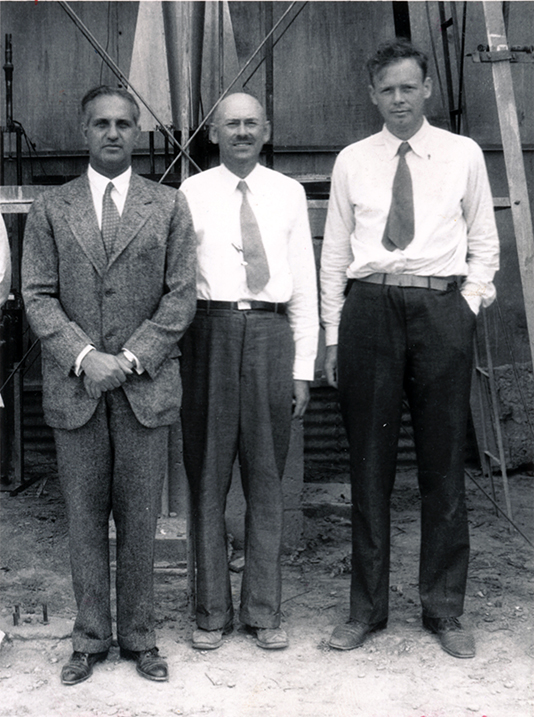

With Thanksgiving less than a week away, the campus was quiet on the late afternoon of Saturday, November 23, 1929. Only three students were working in the science building’s chemistry lab when a lanky, fair-haired young man walked in and inquired after Dr. Robert Goddard.

All three escorted him to Goddard’s office, for the visitor was none other than Charles Lindbergh, whose nonstop solo flight across the Atlantic two years before had vaulted him to international renown. “LINDY SURPRISES CLARK” screamed the above-the-fold headline in the Clark News, the undergraduate weekly paper. Specifics of their subsequent two-hour meeting remained unknown but the reporter opined that it undoubtedly “had some connection with the recent experiments of Prof. Goddard with high altitude rockets.”

I have been fortunate enough to open a time capsule of Clark from Fall 1928 to Spring 1932 thanks to my eagle-eyed brother, who at a flea market in Maine noticed a stack of Clark News and bought the lot on the spot. The 100+ issues accumulated by Archie Biron (see story below) provide a chronology of collegiate life during the early years of the Great Depression. Occasionally, national events merited coverage, like a straw poll on the eve of Herbert Hoover’s landslide election in November 1928 when he won 137 votes to Democratic candidate Al Smith’s 77. Most astoundingly, socialist Norman Thomas received 37 votes. “There is a need for a third party, it is time to overthrow the hold that these two major political parties have on the American people,” read a prescient op-ed in Clark News.

••••

This cache of papers illuminates the era’s society and culture, with small display ads offering a flavor of local retail options like Biondi-Curran Co. (“correct clothing for young men and their elders”), Buffington’s (“the real drug store of Worcester”), and Downing Spa. But these small businesses are dwarfed by three-quarter and full-page advertisements for tobacco products, with three competitors touting Lucky Strike, Camel, and Chesterfield, which provided free cigarettes at a fraternity smoker featuring a chemistry professor’s talk: “The cigarettes donated by the Chesterfield Man were passed among the 23 present, and a general feeling that all’s well with the world was prevalent.” An innocent time, an insidious practice.

Some activities and events were unique to Clark, chief among them Spree Day and the rope pull. In May 1929, for the first time, Spring Spree was announced in advance, promising “jest and jollity, relief from classes and quizzes for the day.” Besides a picnic and dance, sports reigned with assorted inter-class races and a baseball game won handily by the faculty. The following year they walloped the students even worse, 18-3, but for some the fun and games were wearing thin. “Many students who are busy with studies or outside work feel that holidays are too valuable to be spent romping around the campus … in the pursuits of their boyhood days,” read an editorial. Thankfully, frivolity prevailed.

Clark’s oldest athletic tradition, the annual sophomore-freshman rope pull, produced four straight wins for the sophomores from 1928 to 1931. “Determined Sophomores Pulled Dazed Frosh Thru Cold Waters of University Pond,” reported the paper in 1928. The next year produced “one of the most bitterly contested rope pulls in years” with nearly an hour of “heaving and hauling [with] hands numbed by the cold and blistered from pulling” until the freshmen got their dunking. Crowds swelled to some 5,000 fans, cheering as the winners hauled the rope back to the gym for a reward of doughnuts and hot coffee. In 1931, the day ended with the first dance of the season, then called a boheme, in the auditorium of Jonas Clark Hall to the sounds of an 11-piece orchestra.

Dances were integral to school life, and none more so than the spring prom — truly the bee’s knees for “social lions and their lady guests from far and near.” Festivities began with the formal Junior-Freshman Prom on Friday night and continued with weekend-long receptions, breakfasts, suppers, tea dances, and house parties.

••••

While these annual events enjoyed spotlight status, most activities ran throughout the school year. This age was the heyday of glee clubs, and Clark’s robust lineup competed continuously and was often heard on the radio (WORC). The winter of 1929 reflected a typically busy season. At Framingham Normal School the club and Clark’s orchestra gave a spirited performance that elicited “a visible response from an audience comprised largely of the opposite sex.” Afterward, they serenaded their hostesses with an impromptu “Good Night Ladies” under a dormitory window. At the New England Intercollegiate Glee Club Contest at Boston’s Symphony Hall a week later they sang “Now is the Month of Maying,” “Sons of Clark,” and “Songs My Mother Taught Me.” Later they teamed with clubs from Worcester Tech and Holy Cross for concerts at the Bancroft Hotel and Mechanics Hall.

Other popular clubs included the Debating Society, which argued such weighty issues as whether the United States should recognize the government of the Soviet Union. CUPS staged many performances, including Sir James Barrie’s “Dear Brutus.” A camera club formed in 1931. Collegiate and intramural sports abounded, with extensive weekly coverage of baseball, basketball, soccer, tennis, track, and more.

Clark hosted an array of guest performers. A sampling included Spanish guitarist Andres Segovia, Russian violinist Mischa Elman, composer/pianist Percy Grainger, sculptor Lorado Taft, writers Thornton Wilder and Christopher Morley, German dancers Harald Kreutzberg and Yvonne Georgi, and dancer/choreographer Mary Wigman. Some received rocky receptions: “[Wigman’s] mode of the dance was altogether a new one and was calculated to inspire either disgust or pleasure.” Others won praise, like Wilder, still a few years away from his Pulitzer Prize-winners “Our Town” and “The Skin of Our Teeth”: “Executed by a master in a masterly way, he held the audience motionless throughout the too-brief hour.”

Their performances came in the “enlightening and educating” Fine Arts series spearheaded by English professor Loring Dodd, one of many prominent folks who strode the campus to much acclaim (the Ruth Dodd Residence Hall is named for his wife). President Wallace Atwood’s duties never seemed to preclude extensive travel. At a Royal Geographical Society conference in London he hobnobbed with British royalty including H.R.H. Prince of Wales, later King Edward VIII, who would abdicate the throne in 1938 after less than a year to marry American divorcee Wallis Simpson. Dean Homer Little’s travel talk, “A Ramble About the Mediterranean,” featured slides from historic ruins in Egypt, Greece and the Holy Land. A few months after meeting Lindbergh, Goddard decamped to Roswell, New Mexico, to continue his groundbreaking experiments in rocketry.

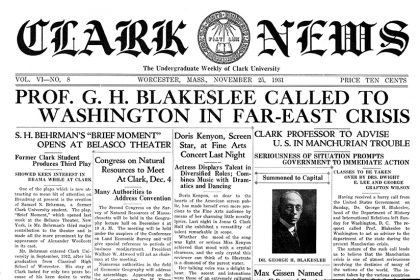

Ominous drumbeats of war were sounding. The State Department summoned History Department chair George Blakeslee, a Far East expert, to Washington to advise on Japan’s invasion of Manchuria. In February 1932 he sailed for Peiping (Beijing) to assist the U.S. ambassador. An op-ed lauded his selection and supported an economic boycott of Japan: “If this plan does not accomplish its planned effect there is always time to use crude but effective armed intervention.” The next month an op-ed warned that the victory of aging Paul von Hindenburg over Adolf Hitler in Germany’s presidential election did not “assure for any considerable time that Fascism is a dead issue.”

Many Clark students and alumni, including Archie Biron, would answer the call to serve less than a decade later when the attack on Pearl Harbor brought the U.S. into World War II.

The long legacy of Archie Biron

Pittsfield, Mass., native Archie Henry Biron (1911-1995) graduated from Clark in 1932. His Pasticcio profile described his major interest as romance languages and his future plans as teaching. He nailed them both. Biron subsequently earned a diploma from the Institut de Phonétique at the University of Paris and a master’s degree from Middlebury College. He married Dorothy Gay of Westfield, N.J., and returned to France during World War II as a soldier in the U.S. Army. After the war, he taught at Riverdale Country School in New York City, and later at Rutgers University. In 1950 he joined the staff of Colby College where he taught for nearly 30 years and was instrumental in developing its foreign language programs abroad. While the Birons traveled extensively in Europe, North Africa, and Canada, he never relinquished his collection of Clark News, allowing for this serendipitous rediscovery a quarter century after his passing.

Pittsfield, Mass., native Archie Henry Biron (1911-1995) graduated from Clark in 1932. His Pasticcio profile described his major interest as romance languages and his future plans as teaching. He nailed them both. Biron subsequently earned a diploma from the Institut de Phonétique at the University of Paris and a master’s degree from Middlebury College. He married Dorothy Gay of Westfield, N.J., and returned to France during World War II as a soldier in the U.S. Army. After the war, he taught at Riverdale Country School in New York City, and later at Rutgers University. In 1950 he joined the staff of Colby College where he taught for nearly 30 years and was instrumental in developing its foreign language programs abroad. While the Birons traveled extensively in Europe, North Africa, and Canada, he never relinquished his collection of Clark News, allowing for this serendipitous rediscovery a quarter century after his passing.

The most recent book by Washington, D.C.-based writer Harvey Solomon ’74 is “Such Splendid Prisons: Diplomatic Detainment in America during World War II” (Potomac Books, 2020). “With sharp characterization, crackling prose and an eye for humorous detail, Solomon takes us on a wild Technicolor ride … His prodigious research has cracked the code of silence surrounding the secretive detention of Axis diplomats and their families.” (Max Paul Friedman, American University)