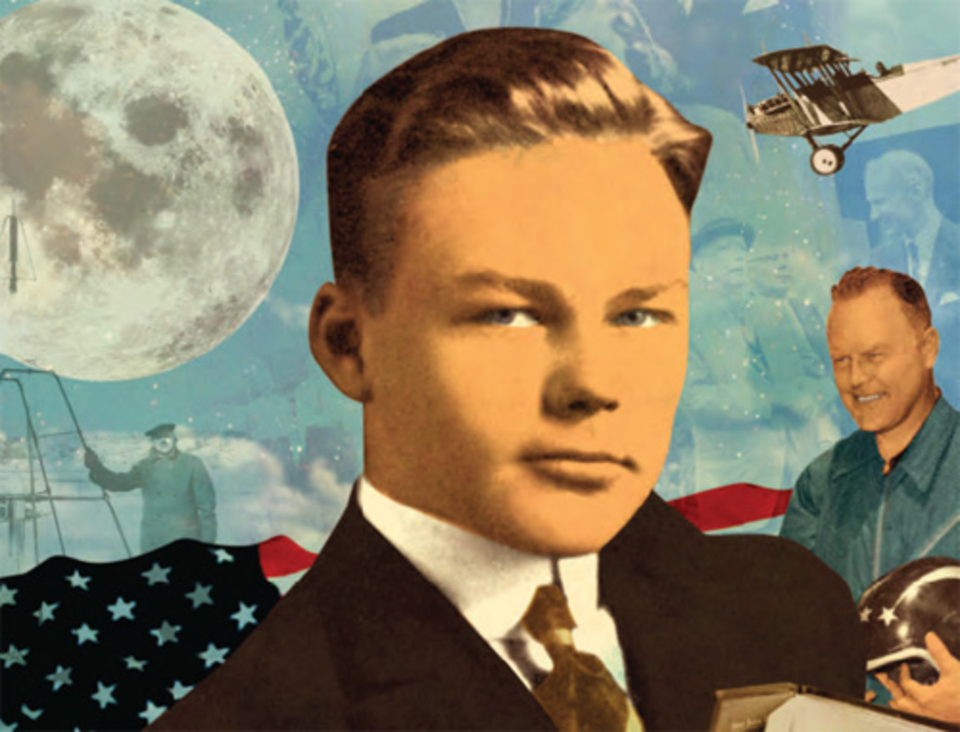

From Clark to the Moon

“Can you hear me all right? There’s a little bit of street noise here.”

Buzz Aldrin — moonwalker, author, dancer with the stars — is talking on his cell phone outside a busy Los Angeles restaurant, battling the drone of cars whipping by him. But his voice is clear and strong, and besides, he’s in the mood to talk. His media representative had allotted fifteen minutes of conversation with the 81-year-old former astronaut; Aldrin will give forty-five.

What’s intrigued him this day is the topic: his father, Edwin Eugene Aldrin Sr., Clark University Class of 1915. While Buzz Aldrin earned a headline in history as the second man to walk on the moon, Aldrin Sr. was himself an aviation pioneer who crisscrossed the country by air and broke bread with some of American history’s most galvanizing figures of flight. He studied physics under Clark Professor Robert Goddard, the Father of Modern Rocketry, and drank with Howard Hughes at The Wings Club in Manhattan when the billionaire industrialist was building cutting-edge aircraft and making fighter-pilot movies.

Astronaut Buzz Aldrin is interviewed by phone from Los Angeles about his father, Edwin Aldrin, Sr.

Edwin Aldrin counted among his friends airplane inventor Orville Wright, and Jimmy Doolittle, whose squadron of B-25s conducted the bombing of Tokyo in 1942, known forever as Doolittle’s Raid.

His son also contends that Edwin arranged a fateful meeting involving another acquaintance, Charles Lindbergh, that helped usher in the very Space Age that would turn Buzz into an American icon.

The history books recount that Goddard, who taught physics at Clark for 29 years, was scrounging for the money needed to continue his revolutionary rocket experiments. News of his plight reached Lindbergh, who visited Goddard in Worcester. Convinced of the scientist’s vision that a rocket could one day travel to the moon, Lindbergh prevailed upon the Guggenheim family to finance Goddard’s experiments through the Guggenheim Foundation for the Promotion of Aeronautics. With funding finally in hand, Goddard in 1930 was able to take an extended leave from his Clark post and head for the open desert of Roswell, New Mexico, to work on his test rockets.

Buzz Aldrin offers an expanded version of the story.

“Dad was aware in the mid-1920s that Goddard needed funding for his rocket work,” Aldrin says. “He knew Guggenheim had a lot of money, but it was obvious that Guggenheim wouldn’t know who Eddie Aldrin was. So Eddie went to Charles Lindbergh and asked him to put in a good word with Harry Guggenheim. He did, and Goddard got his funding. Everyone thinks it was Lindbergh who did all that, but it was really Dad who saw the need.”

“Dad was aware in the mid-1920s that Goddard needed funding for his rocket work,” Aldrin says. “He knew Guggenheim had a lot of money, but it was obvious that Guggenheim wouldn’t know who Eddie Aldrin was. So Eddie went to Charles Lindbergh and asked him to put in a good word with Harry Guggenheim. He did, and Goddard got his funding. Everyone thinks it was Lindbergh who did all that, but it was really Dad who saw the need.”

Understandably, Edwin Eugene Aldrin’s Clark senior yearbook profile offers no clues that he would seek a life largely spent in the skies. The Wright brothers had made the first powered airplane flight at Kitty Hawk only 12 years earlier, and aside from the World War I exploits of ace fighter pilots, the notion of being airborne still seemed an outlandish prospect.

The Worcester native, who was nicknamed “Shrimp” for his diminutive size, majored in German as an undergraduate, was a member of the Kappa Phi fraternity, performed in the play “The Enemy of the People” and pulled the trigger for the Senior Rifle Team. His profile describes a young man teeming with “good humor and optimism” who never seemed ill at ease, and it takes a good-natured poke at his study habits: “He has never become thin with overstudy or worn away his expansive smile with too much strenuous work.” Aldrin played along. “Life is too short and art is too long,” he wrote in the yearbook, “for the over-consumption of my grey matter.”

The truth is that Edwin Aldrin was driven. Following graduation he studied math and physics — Goddard was his professor in 1915/16 — at Clark and Worcester Polytechnic Institute before earning his doctorate in aeronautical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Decades later, Buzz would also enroll at MIT, becoming the first astronaut to hold a doctorate. (Buzz Aldrin notes his own advanced education did not endear him to the other astronauts, and he consistently earned low scores in NASA’s peer-rating system. “Here was this egghead from MIT without test-pilot training working with the instructors who were teaching these hot-shots. Clearly, my group did not put me at the top of their list,” he says.)

In 1917, Edwin Aldrin was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Coast Artillery, but transferred to the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps — where, Buzz says, “he bootstrapped his way into learning how to fly.” The Aviation Section was later designated as the Army Air Service, then the Air Corps, and finally the U.S. Air Force.

One of his early assignments was chief of the School Section of the Engineering Division at McCook Field in Dayton, Ohio, where he met Orville Wright. Aldrin served as commandant at the Air Force Engineering School, which became the Air Force Institute of Technology.

Throughout the 1920s and ’30s, Edwin Aldrin earned a reputation as a skilled aviator at a time when flying an airplane was such a rare pursuit that it was considered by many as the sole province of daredevils and barnstormers. Aldrin was a judge at the Cleveland National Air Races that attracted the best pilots in the U.S. to compete in a variety of airborne competitions, including a cross-country race. In 1929, he set a U.S. cross-country record, flying from Glendale, Calif., to Newark, N.J., in 15 hours and 45 minutes, surpassing the old mark by three hours. He later flew to Germany aboard the Hindenburg, and as young Buzz would delight in telling his friends, his father predicted that the famous zeppelin would one day crash, which it did in spectacular fashion in 1937 in Lakehurst, N.J.

The elder Aldrin’s reputation spanned continents. A story in the Worcester Sunday Telegram tells of an incident in 1930 in which two French aviators, on a goodwill flight to Cleveland, dropped a silk American flag over the WPI campus. The flag was wrapped in paper, which was inscribed, “Felicitations to Worcester – Hometown of Maj. Aldrin.”

That same year, 1930, Edwin Eugene Aldrin Jr. was born, the third child and only boy of Edwin Sr. and his wife Marion. (He was nicknamed Buzz when one of his sisters kept pronouncing the word “brother” as “buzzer.” Edwin Jr. would later officially change his name to Buzz.)

Edwin had met Marion Moon, the daughter of an Army chaplain, in the Philippines when he was working as an aide to Gen. Billy Mitchell. The cosmic coincidence of her maiden name would only be realized four decades later.

In 1928, Aldrin had accepted a job with Standard Oil, heading up the company’s fledgling aviation division. Though based at 30 Rockefeller Plaza in New York, he flew all over the U.S. and Europe preaching the virtues of commercial air travel and was widely acknowledged as one of the country’s first flying executives. In Europe he flew a 6,000-mile tour of 12 European capitals, setting several city-to-city speed records.

Home base was New Jersey, where the Aldrins settled at the urging of another Clark graduate.

“Harold Ferguson was dad’s fraternity brother at Clark,” Buzz Aldrin recalls. “Ferguson moved to New Jersey and became principal of the high school in Montclair. Dad was living in East Orange and commuting to New York. Harold said, ‘Eddie, why don’t you move to Montclair, it’s a really nice community.’ So Dad cashed in some of his stock in Standard Oil in October 1929 before the Crash, and he moved to upper Montclair on the same street as Harold Ferguson.”

Edwin Aldrin Sr. was a fixture in Buzz’s life, but like many a father-son relationship theirs was complicated. In his memoirs “Return to Earth” and “Magnificent Desolation,” Buzz Aldrin writes that his father demanded excellence from his son in every endeavor from academics to athletics, and, backed by a powerful personality, the senior Aldrin often held sway. But the two also clashed, notably over Buzz’s decision to attend West Point in defiance of Edwin’s wish that Buzz enter the Naval Academy. Edwin also objected to his son becoming a fighter pilot during the Korean War, preferring that Buzz fly stateside as part of the national air defense.

Though he could be stern and difficult to please, Edwin also would rally around Buzz. Aldrin recounts the times his parents would drive to West Point from Montclair with bags of forbidden candy for Buzz and his roommate to smuggle into the dorm.

In “Return to Earth,” Aldrin writes of his father:

“Even when he was away during World War II, his influence on our household, especially on me, was strong. He planted his own goals and aspirations in me. When I set a goal he encouraged me. When I conquered a goal he expressed the importance of still another, bigger one. I, in turn, strove mightily for his approval.”

Edwin left little doubt that his son would share his passion for flight. He took Buzz on his first plane ride when he was two years old, flying his son and the family housekeeper to Florida in Standard Oil’s Lockheed Vega. One can imagine the boy’s wonder as he soared in an aircraft painted to look like a flying eagle with outspread wings and claw-like wheels. So distinguished was the plane that a model of it was mounted in the Smithsonian Institution.

Despite his own connection to Goddard’s rocketry research, Edwin was skeptical about the astronaut program and instead had envisioned a military career for Buzz.

“Dad was well connected, and one time I asked him what my chances looked like for being selected as an astronaut,” Aldrin recalls on the phone from L.A. “He asked a few questions around Washington, and told me, ‘Well, I checked around and it doesn’t look like you’re still in the running. But that’s okay because you didn’t want to do that anyway.’ I said, ‘No Dad, you’re wrong.’ I really did want to get into the astronaut business.

“As he began to look into the program, he picked up on what he felt was a significant shortcoming as far as his son was concerned, and that was that NASA didn’t have a rescue capability. In an interview, my father talked about that, without realizing there was no way we could have a second Saturn 5 [rocket] with a crew standing by to launch and rescue the first crew if we ran into trouble. We had the best redundancy we could possibly have, but there was no rescuing someone stranded on the moon.”

Faded newspaper clippings and Google searches hardly do justice to the white-hot frenzy that accompanied the July 20, 1969, lunar landing and the difficulty the astronauts experienced dealing with its aftermath. The Aldrins had first been thrust into the national spotlight when Buzz went into orbit in 1966 aboard Gemini 12, the last mission featuring a two-man spacecraft. The notoriety was a mild precursor to the national obsession that would greet the moon launch. To this day, Aldrin blames his mother’s 1968 suicide on the relentless public scrutiny leveled at his family following the Gemini mission and prior to the moon shot.

In his memoirs, Buzz Aldrin writes unsparingly about his battles with alcoholism and depression in the years following the moon landing. His father’s reaction — “He was nearly apoplectic,” Buzz remembers — when he learned Buzz wanted to publicly reveal his personal demons reflected his own desire to protect his son from criticism and preserve Buzz’s image. But it was also a characteristic response from someone who would never experience the public-confessional ethos shaped by Oprah, Dr. Phil, and others who turned therapy into a pop-culture phenomenon.

The retired Air Force colonel was ever reluctant to admit that his son’s depression could stem from internal struggles and instead suggested that his walk on the moon may have played a part in altering Buzz’s behavior. As he told a reporter, “Who is all-seeing to know what effect the moon might have on people? If the moon can affect tides, why couldn’t it influence someone’s judgment? We may be afraid of the answers, and Buzz deserves credit to come out and face that situation.”

That Edwin Aldrin remained fiercely protective of his son’s legacy is indisputable. In an April 16, 1969, letter to Goddard Library Assistant Director Arnold Bailey, one month before Buzz Aldrin would cut the ribbon on the new library, Aldrin Sr. lamented that NASA had failed to provide Clark with an updated photograph of Buzz to accompany his biography in the program.

“This has been delayed, even though I have complained,” he wrote. “Maybe your strong request would bring action. Don’t ask Buzz. Ask topside. This is disgraceful. ($25 billion spent [on the space program] and no pic!).”

Edwin also objected to the idea that Neil Armstrong would precede his son down the ladder from the lunar module and onto the moon’s surface.

“He didn’t quite understand the pecking order of seniority that dictated the commander would be the first person to go out,” Buzz Aldrin says. “It almost would have been an embarrassment for Neil to sit up in the cabin looking out the window while his junior person went down the ladder and said …” He hesitates, then chuckles. “Well, I don’t know what I would have said.”

The sense that his son had been slighted never left Edwin Aldrin. Buzz recalls that when the U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp with Neil Armstrong’s image accompanied by the caption, “First Man on the Moon,” his father was so outraged that he picketed the White House holding a placard bearing the message, “My Son Was First, Too.”

The public’s mania for all things space-related was in full flower on May 19, 1969, a mere two months before the historic Apollo 11 launch. On that day, Buzz Aldrin helped cut the ribbon on Clark University’s new Robert Hutchings Goddard Library, whose then-radical design and educational mission honored the scientist’s legacy. Among the luminaries present were Sen. Edward Kennedy, who chose the occasion to propose a reduction in NASA spending, and Wernher von Braun, the German rocket scientist who was a leading architect of the U.S. space program. (The trip to Clark was a pilgrimage of sorts for von Braun, who proclaimed Goddard one of his childhood heroes.)

Photos from the event reveal a crowd of more than 3,000 onlookers and a media army staked out on the Clark greensward, with print, radio and TV reporters recording every uttered word, every smile and backslap, and the awarding of every honorary degree, including one to Aldrin.

Also pictured rubbing elbows is Edwin Eugene Aldrin ’15, whose presence at the event was, outside that of Robert Goddard’s widow, Esther, perhaps the most appropriate of all. Here, after all, was the man who saw a future in flight; who perceived the value of Goddard’s rocket experiments enough to recruit Charles Lindbergh to the cause; whose son would become the living embodiment of Goddard’s quest to put a man on the moon.

Buzz Aldrin says his father, who suffered a fatal heart attack in 1974, lived with a certain measure of ambivalence about remaining on the fringes of history while others took center stage.

“Dad never felt he got his due for his efforts in the Air Force. He just didn’t feel like he was ever fully recognized,” says Aldrin as the cars continue to zoom by on this Los Angeles morning.

But what were his father’s feelings toward that boy of his, who escaped Earth’s atmosphere and left footprints on the moon?

“Oh, he was proud,” the astronaut says. “Absolutely.”

This story was originally published in CLARK Magazine, fall 2011.