Professor Rudolph Nunnemacher emerged from his office carrying the lens of a whale’s eye. The electricity to the biology building was temporarily out of service, and he had just the remedy to brighten the darkness.

He said to me, ‘Come watch this,’ remembers Michael Rosenzweig ’85, who followed obediently to the door of the professor’s unlit biology classroom filled with students.

“‘May I have your attention, please!’” shouted Nunnemacher. “‘Arctic peoples longed for the sunshine after their cold, dark winters, and they had a chant they would do, just like our Clark University motto Fiat Lux, which means, of course, let there be light.’”

“Then Nunni proceeded to raise the object into the air,” continues Rosenzweig, “and says to his class, ‘If you repeat after me, maybe we can get the electricity to come back on. Let there be light! Let there be light! Finally, the whole class was chanting ‘Let there be light!’ And whoosh, the power comes on. Nunni walked out the door, looked at me, and said, ‘Pretty good, huh?’”

“He was one of the reasons I came to Clark, one of the reasons I enjoyed being at Clark, and one of the reasons I remember Clark so well.”

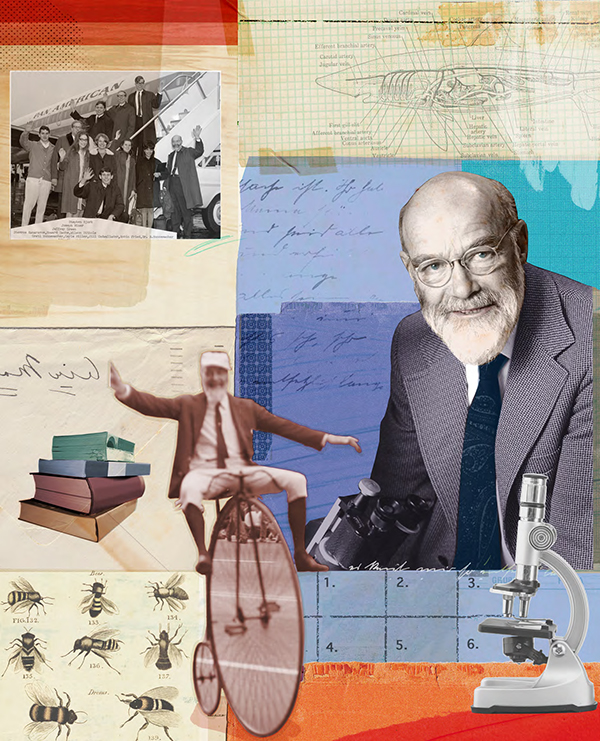

From 1938 to 1983, through the course of his remarkable Clark career, Rudolph Nunnemacher always brought the light to his classroom. Small in stature, with a neatly trimmed beard that faded over time from red to white, his was a formidable presence that made him alternately feared and revered by his students. The Harvard-trained biologist from a well-to-do Milwaukee family dressed formally in coat and tie, his only concession to summer’s heat being the Bermuda shorts that replaced long pants. Says David Hawkins ’83, “When Nunni walked into the room, everyone noticed.”

A stickler for proper behavior and with a reputation for intellectual brilliance, he nevertheless displayed an impish, and occasionally outrageous, sense of humor. Nunnemacher was, for example, rumored to have demonstrated the power of peristalsis — the swallowing reflex — by drinking a glass of water while standing on his head. Perhaps this is why former students so comfortably and affectionately refer to him as “Nunni.”

“He was a great lecturer,” recalls Dr. Herbert Hoffner ’55. “He had a unique way of presenting the material so that you got a chuckle out of the whole thing. But he didn’t forget the important parts.”

Hawkins recounts how, toward the end of a lecture on hymenoptera — the order that includes ants, bees and wasps — Nunnemacher, then in his 70s, inexplicably disappeared behind the desk at the front of the classroom. He emerged wearing a yellow- and black-striped rugby shirt with two antennae stuck on his head to deliver a lecture — in verse, no less — about the sex life of bees.

“It was quite graphic, but with bee anatomy,” Hawkins says. “Everyone in the room was just cracking up. Then they applauded, and he bowed and left.”

Nunnemacher also was famous for owning a succession of boa constrictors — Humphrey, Ophelia, Franz and Monty — that he kept in a glass cage in the biology building.

Tom Dolan ’62, M.A.Ed. ’63, retains vivid memories of the boas at feeding time.

“That was a big show,” he says. “I think he fed them every three weeks or so. They were his pets. He would pick them up and the rest of us would run out of the room.”

Nunnemacher, a devoted member of The Wheelmen, an organization for cycling enthusiasts, enjoyed riding his high-wheeled penny farthing in local parades. On at least one occasion he sported a live boa draped around his neck as he pedaled.

Professor Nunnemacher’s implementation of the Socratic method was a technique he might spring upon an unwary student anytime, anywhere. Hawkins describes the professor handing him a lump of unidentified material, then asking a series of questions to guide him toward the correct answer. “Eventually, I said that it’s something regurgitated by a whale,” he recalls.

“Nunni said, ‘That’s right, Mr. Hawkins! It’s whale vomit!’ “Every time you talked to the man, you’d learn something,” says Hawkins. “But mostly what you’d learn is how to figure things out. And he walked you through the process in a way that was truly magical.”

“Every time you talked to the man, you’d learn something. But mostly what you’d learn is how to figure things out.”

Nunnemacher was famous for the one-on-one oral examinations he gave at the end of his Comparative Anatomy course, grillings that induced significant anxiety in his students. The misery was compounded by Nunnemacher’s expectation that his students would present themselves suitably attired, which for men meant suit and tie. They were also required to bring along the smelly, formalin-saturated, 2-foot-long dogfish shark they had been dissecting during the semester.

“I went into Nunni’s office wearing my suit and tie and put my shark down,” Hawkins remembers. “I sat down, and it was really intimidating. When he looked into your eyes, it was like he saw right down to your soul.”

In Hawkins’ exam, Nunnemacher told a story from “Alice in Wonderland” involving a walrus, a carpenter and oysters, which not only put his student at ease but expertly folded into the subject of shark anatomy.

“He well knew what his students had been doing on their sharks, and what they might have challenges with,” Hawkins says. “The challenge for me was being so nervous that I would freeze.”

Tom Leonard ’62 had a similar response to the dreaded oral exam.

“I couldn’t eat all day,” he recalls. “But Nunni would ease you into the hard questions, and when he saw you fumbling, he’d move on to another question. So he was very kind in that way, because he could flatten you.”

Nunnemacher so unnerved his students that before class field trips they would sometimes flip a coin to determine who would have to sit next to him on the bus. Inevitably, the experience was far more pleasant than anticipated.

“When you got to know him, he was wonderful. Like an uncle,” Leonard says. “He wasn’t a guy who just walked up and put his arm around you. You didn’t small-talk Nunnemacher. But he was just so warm and so nice to me. He was probably that way with all students who broke the ice.”

Leonard describes returning home to Worcester from Indiana, where he was completing his Ph.D., and realizing he didn’t have enough money for the return trip.

“Nunnemacher asked me, ‘How much do you want?’ I think he gave me $500. He said, ‘That’s for travel and food for the next month.’ I was broke all the time, and he took good care of me.”

Leonard returned to teach at Clark (1994-2007), and would follow in his professor’s footsteps as chair of the Biology Department. Rosenzweig is now senior instructor and biological sciences outreach coordinator in the Department of Biological Sciences at Virginia Tech, and Hawkins teaches geology at Wellesley College. They incorporate aspects of Nunnemacher’s teaching style into their own approaches as educators.

“In every way a teacher could have an attribute, he was superb,” Leonard says. “When I became a professor, I had clearly in mind the things I learned from him.”

Rosenzweig learned from his mentor that “you had to both teach and entertain if you’re going to be successful.”

Susan Cormier, Ph.D. ’82, a senior scientist with the Environmental Protection Agency, recalls Nunnemacher’s insistence that students explain the reasoning behind their answers. “He was always teaching people how to figure something out from the basic science, the basic observations that were available to you,” she says. “I think as a result, there are a lot of doctors out there who are much better than they would have been otherwise.”

Nunnemacher’s office at Clark was legendary — a sort of “cabinet of curiosities,” full of biological specimens. Daughter Gretl Nunnemacher ’70 characterizes her father’s space as “an extension of the home I grew up in.” She recalls among the collection a narwhal tusk, an old ophthalmoscope (a device for showing the workings of the muscles of the eye), and a stuffed pheasant that had been shot by Clark’s first president G. Stanley Hall on a tour through Europe.

A retired electron microscopist and the only one of Nunnemacher’s four children to pursue a scientific career, Gretl says her father had “the soul of an artist.”

Indeed, Nunnemacher was an enthusiastic watercolorist who introduced a number of his students to the pleasures and challenges of painting. One of them was Dr. Carl Rosengart ’55, who traveled by van with his classmates on several Saturday mornings to various locations around Princeton, Mass., where they practiced basic watercolor techniques by painting fields and barns. Later, during class time, they would put their newly acquired skills to use by painting images of the tissues they viewed under the microscope.

“I still paint,” says Rosengart, whose work hangs in Tilton Hall. “Clark was undoubtedly the best four years of my life. It was just an extraordinary experience, and Nunnemacher was part of it.”

The professor’s strong presence was felt in other areas as well.

In 1957, Nunnemacher began his long affiliation with the Bermuda Biological Station (now the Bermuda Institute of Ocean Sciences), first doing research there on the eyes and nervous systems of crustaceans. Beginning in the 1960s, he led week-long research trips for Clark students to Bermuda, sometimes referring to his students as nudibranchs — a reference to a brilliantly colored mollusk for which he harbored a special fondness. Clark biology students continue to travel to Bermuda to this day, the research trips partly funded through the Nunnemacher Award, which he endowed. The Nunnemacher Nature Reserve in Bermuda was dedicated in his honor in 1996.

In waters closer to home, he developed and was the coach of the first Clark women’s crew team, celebrating its 75th anniversary this fall. The “Nunni” was added to the crew’s three-scull fleet in 1963, and a shell named in his honor has been part of the program ever since.

“The current rendition bearing his full name is an 11-year-old Vespoli that has been the chariot for most every Clark female oarsman over that time,” says Coach Michael McDonald. “And it has seen a lot of miles.”

Professor Nunnemacher died from cancer in 1988. Before he passed, Michael Rosenzweig paid him a visit.

“I think he knew he was sick, but he didn’t tell me, of course,” Rosenzweig says. “He was older, frailer than I had expected. It was a very emotional meeting — it seemed a big deal to him that I cared to come back and give him my reflections on being an undergrad at Clark.

“He was one of the reasons I came to Clark, one of the reasons I enjoyed being at Clark, and one of the reasons I remember Clark so well.”

Heteropsyllus Nunni, a minute crustacean inhabiting estuaries along the East Coast of North America, was named in honor of Rudolph Nunnemacher. It is a humble namesake for a humble man, yet doesn’t quite capture the force of nature that he was. Of course, Nunni’s true legacy rests in the University’s labs and classrooms, where he lit countless intellectual fires before sending all those Clark nudibranchs out into the world.