The following is a chapter from “Changing the World: Clark University’s Pioneering People, 1887–2000” (Chandler House Press, 2005), by former Clark president Richard P. Traina.

Clark professor Robert W. Kates’ research career moves from natural and then technological hazards, to changes in Earth’s climate, to world hunger, to global environmental sustainability. The pervasive, even transcendent, themes in his work are: How does humankind use the earth, and how ought humankind use the earth? With remarkable commitment and intensity, Kates combines an insistence on an encompassing vision with a readiness to engage the most vexing practical complexity. Sherburne Abbott, a widely recognized leader in the field of sustainable development, calls Kates “a major figure for restructuring thinking about the interaction of humankind and the environment.” Gilbert White, for decades a leading intellectual in the world of geographical and environmental research and Kates’ early mentor at the University of Chicago, wrote:

“Bob has made a number of original contributions to thinking about geographical problems, but his part in exploring the meaning and implications of sustainability science have been the most recent and probably the most significant.”

Kates’ route to such achievement and prominence was hardly straight or intentional. Born in 1929 into a modest Brooklyn family impacted by the Great Depression, he attended New York University in the late 1940s. He left after two years, when he and Eleanor Claire Hackman decided to marry. “Ellie” quickly became Bob’s special confidante and “gyrostat.” During the 1950s, they were settled with their three children in northern Indiana, where Kates worked at a Gary steel mill. In 1957, Bob made an innocent but defining decision. He had understood that there were elementary-school teachers who worked in national parks, and he and his family very much enjoyed the outdoors. He decided to pursue teacher certification. Using a union benefit to attend evening classes at an Indiana University extension, he took a course in resource management taught by Martha Church, then a graduate student in geography at the University of Chicago. Church, later the president of Hood College, reflected on the experience: “Bob already had the spark; all I did was fan it a little.” She was so vividly impressed by Kates’ brilliance that she introduced him to Gilbert White. White’s immediate impression was clear: “If anything, Martha had underestimated him. … His analytical power was evident.” White then arranged to admit Kates to graduate study, despite his lack of a bachelor’s degree. Making the point that his graduate study would have to be a team effort, Kates had brought his family with him to the initial interview. This collaborative attitude toward family, subsequently extended to professional colleagues, has marked his life.

At first, Kates struggled with his dual demands of working at the steel mill and pursuing graduate studies at Chicago. Then, as a full-time doctoral student (probably to the relief of both the mill and the union), he was encouraged by White to study agricultural flood plains and flood damage. Here was early evidence of the freshness and angularity of Kates’ intellect: he did not stop with understanding the physical challenges of floods, he moved on to the affected people’s attitudes about and behaviors toward floods and the flood-threatened areas in which they lived. He was, as it turned out, moving in a direction consonant with that of a young, creative psychologist at Clark University, Seymour Wapner — that is, toward what was labeled, at first perhaps humorously, “psychogeography.” When later both Kates and Wapner were on the Clark faculty, the University would become the primary residence of a developing and now expanding field of environmental psychology.

Kates arrived at Clark University in 1962, with his Chicago doctoral degree in hand, having made the close acquaintance of yet another notable Clark figure, Roger Kasperson. Kasperson is a Clark undergraduate alumnus and Chicago graduate school alumnus who returned to his Worcester alma mater as a faculty member to achieve international distinction in the fields of geography and environment, particularly in the area of hazards research. With this core, the University began to attract in geography and in other fields a cadre of world-class scholars interested in various issues involving humankind’s relationship with nature. The list of people working to challenge convention, related to one another through what has since become the George Perkins Marsh Institute at Clark, includes such individuals as: Billie Lee Turner II, Christoph Hohenemser, Robert Goble, Halina Brown and Kasperson. Kates was clearly the fulcrum, the quintessential emanator.

Five years after his arrival at Clark and the publication of several works on natural resources, Kates, accompanied by his family, was sent on a three-year tour of duty to Tanzania by the Rockefeller Foundation. It was another defining experience, for his concern for natural resources and hazards, and humankind’s relationship to them, began to take on a global character. Evidence of this is found in the widening series of international assignments he took on with a variety of United States, United Nations and other international agencies experiences that only heightened his orientation toward global considerations. Over time, working most closely with his Clark colleagues, Kates moved increasingly in the direction of man-made, or technological hazards, with fresh perspectives analogous to those he had brought to natural hazards. Kates was progressively help-ing to break down the institutional and even linguistic barriers between the sciences and social sciences, and also the humanities, that characterized the academic world and perforce the way human kind and planet earth are viewed and valued.

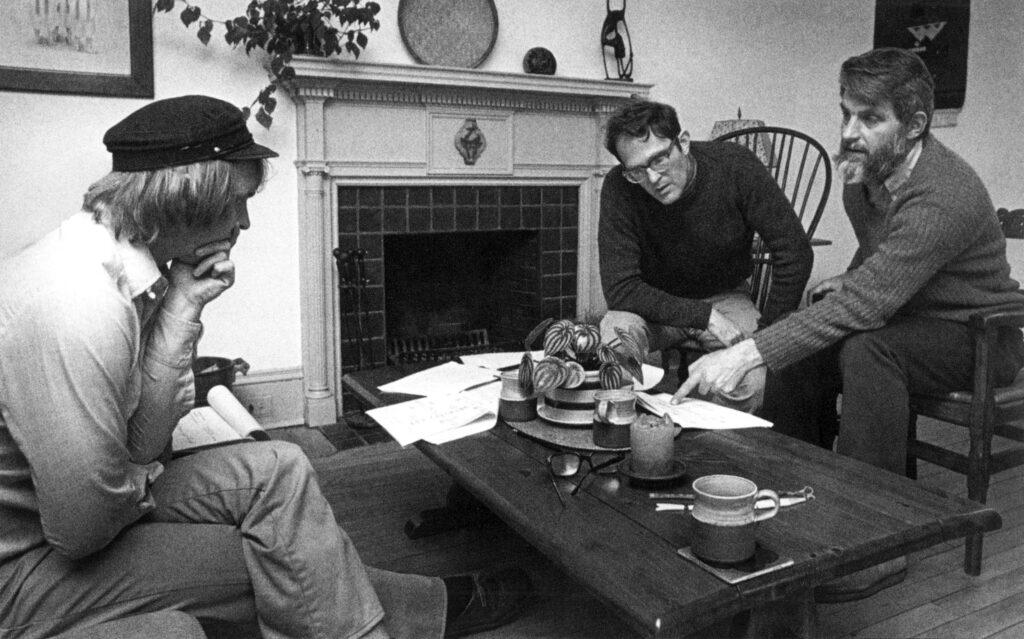

“Earth Transformed by Human Action,” a historic international conference sponsored by Clark University in 1987, was expertly organized and led by Turner, along with William C. Clark of Harvard and Kates. But, it was inspired and made possible first by Kates’ genius. The conference was followed by a massive volume with the same title, with expert contributors from around the world — and it bears the marks of Kates influence on recent approaches to understanding and contending with the relationship between nature and society, including regional and global climate changes.

The range and the brilliance of Kates’ achievements had already caused him to be named a MacArthur Foundation Fellow in 1981. And five years later, Kates was attracted to Brown University to lead the Alan Shawn Feinstein Program in World Hunger, where he and his colleagues worked on the question: What would a comprehensive program to end half of the world’s hunger look like? They made significant progress in analytical terms, but the major obstacle to real progress is something that plagues much of what Kates would have humankind accomplish: It is not enough to be conscious that a problem needs solving, or even to know what must be done to solve it or mitigate it; leadership and will must both be present. Kates carries with him the conviction that we must have that knowledge and judgment ready for the day when both governmental leadership and social will are sufficient to attack such challenging and long-term problems. Human communities are typically too distracted by near-term priorities.

One key question relating to world hunger also relates to the most recent stage of Kates’ career: How do we feed the world with benign effect on the environment? The even more encompassing issue has to do with environmental sustainability generally, and, for Kates, that concerns how we transition to a sustainable world. He asks, put simply here: Can we achieve, through calculated action, a sustainable harmony between humankind and the environment? Kates has been a leader in bringing together a community of scholars and other environment/development leaders from around the globe to tackle this issue on regional and global levels. He co-chaired with the talented Bill Clark, with whom he has long worked closely, the National Research Council’s study that produced the influential publication, “Our Common Journey: A Transition Toward Sustainability” (1999). And, through the National Academy of Science, Kates has successfully defined a science agenda in the United States and internationally — including continuous encouragement of the Third World Academy of Science through a sustainability initiative.

His ever-growing reputation is marked by a powerful combination of character-istics, as acknowledged by other environmental leaders. There is his conviction that humankind needs scholars dedicated to real-world problems, always thinking ahead and thinking big, while understanding that every step in the right direction is a step in the right direction. Accompanying that is his commitment to the idea that the interaction of humankind and the environment must be viewed holistically-that is, that humans are integral to the environment, not something set apart from or against the environment. A third characteristic, both subtle and consequential, is that human welfare and dignity are at the center of his concerns: one protects an animal or a plant species, for example, because caring about animals and plants is part of being fully human.

Through all his accomplishment, Kates has been recognized as one who gains significant cooperation among people across many categories by: sharing, not forcing, ideas; encouraging collaboration and assuming that consequential agreement can be reached; not aggrandizing credit to himself; believing that “synthetic science” (produced collaboratively by people from a variety of fields) can indeed provide solutions to our most pressing problems; and attempting, however possible, to include stakeholders in the processes of analysis and action.

Henry Adams once wrote in his classic autobiography that the truly educated person reflects the highest forces of the times, meaning both intellectual and moral forces. Certainly, that description fits Robert W. Kates.

Robert W. Kates passed away on April 21, 2018.