‘I was impressed by Clark’s mission, and I connected with it’

Like George O. Poinar Jr., the famous paleobiologist who inspired Michael Crichton’s novel Jurassic Park, Jennifer Hanselman has studied past life on earth to better understand the present.

Hanselman joined Clark University as associate provost and dean of research in August, having worked for several years in administrative roles at Fitchburg and Westfield state universities and as a regional manager for the Pioneer Valley STEM Network, one of nine networks designated by the Massachusetts STEM Advisory Council, and 14 years as a biology faculty member at Westfield State.

But two decades ago, you could find her leading an expedition to 35 high Andean lakes in Peru and Bolivia as part of her doctoral research in ecology and conservation biology at the Florida Institute of Technology — several years and many miles from her first career as a high school biology teacher.

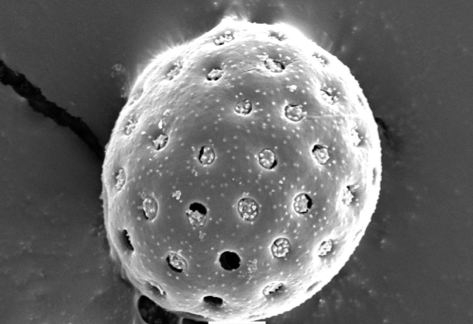

A paleoecologist hunting for prehistoric clues in tropical environments, Hanselman conducted National Science Foundation-funded research, overseeing limnological studies of each Andean lake and extracting surface sediments to analyze pollen and charcoal from thousands of years ago.

“Paleoecology is about past relationships between organisms and their environment. We look at these past relationships and environmental changes to see how these communities may have responded,” she says. “We’re able to take that information and look at what’s going on now to help us predict or mitigate the future.”

While Poinar studied amber-encapsulated plants from millions of years ago in the dinosaur age, Hanselman analyzed a 137-meter core taken from Lake Titicaca, which yielded 370,000 years of data — including microfossils of pollen and spores, as well as charcoal fragments — providing a record of vegetation and fire history spanning multiple glacial cycles.

“These microfossils serve as proxies for climate,” she explains. “You can put timestamps on them, dating them with radioactive isotopes, and identify what’s going on in that time period” in terms of ecosystems and climate, “and what those (plant) communities looked like.”

The pollen she identified provided “a signal for temperature and precipitation,” she says, uncovering climate shifts. Cactus pollen, for instance, would indicate an interglacial time of a hot and dry climate. Or the lack of any type of pollen would indicate a glacial period, or “ice age,” because no plants were growing.

To obtain a fuller picture of how tropical plants and ecosystems have responded to climate shifts throughout the Holocene (the human era), from thousands of years ago until today, Hanselman led an expedition to 35 Andean lakes sitting along an elevational gradient from about 2,800 to 4,700 meters above sea level.

In her dissertation research, Hanselman examined microfossils found in the samples she and other researchers had brought back from the Andes. She also studied miniscule pieces of a sediment core housed in a repository at the University of Minnesota. The core was taken from Lake Titicaca, spanning the border of Bolivia and Peru in the Andes.

“The lake is over 200 meters in water depth, and the core is about 137 meters long,” she says. “It was drilled by a modified oil drilling rig that could float on the lake. It was a fantastic record, over approximately 370,000 years.”

As she and her collaborators examined the samples, “we could document four full glacial cycles, including the distinctive transition times. We could see these shifts in global climate.”

They compared the dynamics of these naturally occurring warming periods with the earth’s current heat-prone scenarios, this time influenced also by humans.

“If we look back at the most recent warming in the mid-Holocene, we see that Lake Titicaca was drying up, and the water level decreased by 80 meters,” Hanselman says. “Going back farther in time to the last interglacial, we saw a lot of salt-tolerant species that were present,” but during the wetter transition periods the Polylepis tree represented more than a third of the fossilized pollen, which might grow abundantly in the Andes today but has been clear-cut.

The large-scale project “was a great example of interdisciplinarity and collaboration. It wasn’t just me or my lab. It was collaboration with researchers across the globe to really understand this complex system. This location in the southern hemisphere is just one piece of the puzzle about global climate, and it was so exciting to be part of that.”

Later in her academic career as a biologist, Hanselman continued to investigate ecosystem dynamics, co-authoring an article, “Modern pollen assemblages of the Neotropics,” published in Journal of Biogeography in 2020.

“I love the idea of thinking about these past relationships and how climate affected them so we can learn for our future, especially with tropical systems being so vulnerable,” Hanselman says. “It’s really something that connected deeply with me.”

She also became deeply invested in STEM literacy, education, and access, including working tirelessly to promote the success of K-12 and university students in Massachusetts. Her work included working with teachers on integration of K-12 science curricula, and addressing ELL needs in the classroom.

Among her many accomplishments as dean of both the School of Business and Technology and the School of Health and Natural Sciences at Fitchburg State, Hanselman oversaw the development of articulation agreements for high school and community college pathways to the four-year institution, as well as the development of graduate school articulation agreements in biology, health, and engineering technology. Under her leadership, the schools secured about $3 million in grant funds to address department needs, enhance faculty development, and promote student engagement in research and other high-impact practices.

“I view my role as an advocate, as a facilitator, and as someone who can work collaboratively to advance Clark forward as we face this changing world.”

— Jennifer hanselman

Hanselman similarly was attracted to Clark because she knew of its stellar research reputation, a commitment to equity in STEM education, and community of engaged scholars, whom she’s found “are deeply committed to collaboration and working together to move things forward.”

Clark’s mission of “challenging convention and changing the world connects the importance of scholarly work to global problems and solutions, and to contributing to society,” Hanselman says. “No matter what their field is, Clark’s scholars contribute to their discipline and educate the next generation of scholars who will solve the world’s problems. I was impressed by that mission, and I connected with it.”

In her first semester here, Hanselman has concentrated on a listening tour, meeting with dozens of faculties, students, staff, and administrators.

Going forward, she sees her role as “helping foster collaboration and inquiry and working with brilliant people who are passionate about their fields.”

That involves, among other goals, supporting faculty researchers and celebrating their accomplishments, identifying and diversifying sources of grant funding, engaging students in research, connecting scholars to collaborate on projects, and raising the visibility of Clark’s research profile.

To that end, Hanselman was integrally involved in planning and celebrating the launch of the Gustaf H. Carlson School of Chemistry and Biochemistry’s new research laboratory, led by Professor Don Spratt — the first in a long line of faculty and grant-funded projects she hopes to promote and support.

The launch drew media coverage and representatives from the Massachusetts Life Sciences Center, which awarded a $750,000 Workforce Development Capital Grant to transform the lab; state legislators; Worcester city, K-12 school, and business officials; and representatives from biotech companies, as well as Clark faculty, staff, and students.

“I view my role as an advocate, as a facilitator,” Hanselman says, “and as someone who can work collaboratively to advance Clark forward as we face this changing world.”