The following is excerpted from “Changing the World: Clark University’s Pioneering People, 1887–2000” (Chandler House Press, 2005), by former Clark president Richard P. Traina.

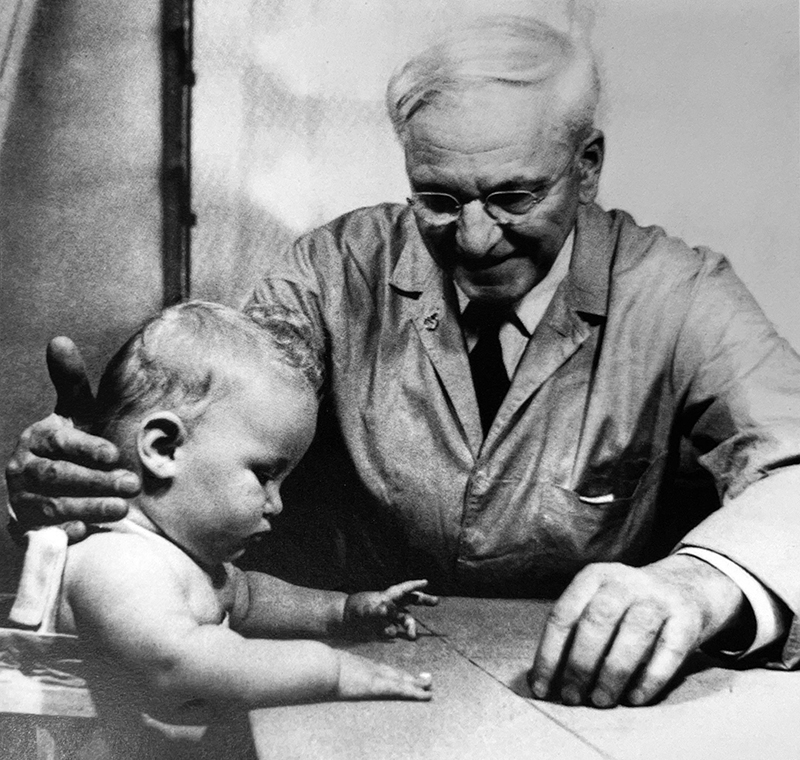

Writing for the American Psychological Association’s centennial series, Esther Thelen and Karen Adolph, two noted psychologists, described Arnold Gesell “as a giant in the field of developmental psychology.” Perhaps even a more accurate descriptor than that already highly laudatory one, is that Gesell was a giant and a pioneer in the broader field of human development—a highly integrated, interdisciplinary field of study.

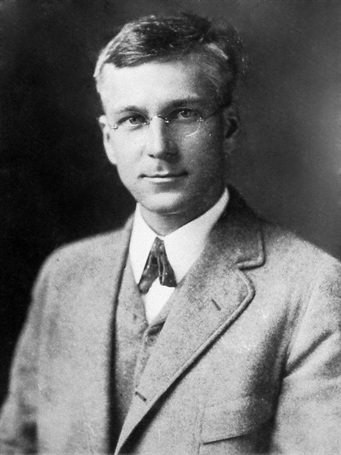

Born in 1880, Gesell was raised in Alma, Wisconsin, on the banks of the upper Mississippi—a town Gesell described as “a picturesque, two street village.” He later wrote, “the very absence of radio, motion pictures, and comics made experiences more vivid, more configured, more eventful.” The eldest of five children in a family that valued education, he very early seemed destined to teach. “The principal of the local high school, in our eyes,” he subsequently explained, “stood at the top of the cultural hierarchy.” In 1899, he graduated from Stevens Point Normal School, where he took a psychology course from Professor Edgar James Swift, a Clark University product who ultimately connected Gesell with his alma mater. Gesell entered the doctoral program in psychology at Clark in 1904, following some high-school teaching and a couple of years studying at the University of Wisconsin.

Years later, Gesell recalled his Clark experience as very powerful and specifically acknowledged his indebtedness to a string of Clark faculty members, including Edmund Sanford, Alexander Chamberlain and the psychiatrist Edward Cowles. He later recognized G. Stanley Hall, “the acknowledged genius of the group.” Hall, Gesell said, “lifted psychology above the sterilities of excessive analysis and pedantry… and I still find in his writings a catalytic quality.” In 1906, Gesell left Clark with his doctoral degree in hand and a dissertation on the subject of jealousy.

Like so many of the early Clark Ph.D.’s in psychology, Gesell immediately went into the trenches, becoming an elementary-school teacher and a settlement worker in New York City, before joining his friend Lewis Terman on the faculty of the Los Angeles State Normal School. There, he met and married Beatrice Chandler, with whom he not only had two children, but also published a book, presciently titled as it turned out, “The Normal Child and Primary Education.” While Gesell was to have a lifelong professional and compassionate interest in who were then known as “backward and defective” children, his major contributions ultimately concerned the development of “normal” young children.

Early in his 30s, Arnold Gesell determined that he “lacked a realistic familiarity with the physical basis and physiological processes of life and growth,” and to “make good this deficit” he “would have to study medicine.” It was a watershed life decision, leading to an appointment in Yale University’s education department, while he earned a degree at Yale Medical School. Gesell made his career in New Haven, where he founded almost immediately the Yale Psycho-Clinic, which evolved into the Yale Clinic of Child Development and later the Gesell Institute of Human Development.

Early in his 30s, Arnold Gesell determined that he “lacked a realistic familiarity with the physical basis and physiological processes of life and growth,” and to “make good this deficit” he “would have to study medicine.” It was a watershed life decision, leading to an appointment in Yale University’s education department, while he earned a degree at Yale Medical School. Gesell made his career in New Haven, where he founded almost immediately the Yale Psycho-Clinic, which evolved into the Yale Clinic of Child Development and later the Gesell Institute of Human Development.

For another four decades, Gesell had a profound impact on shaping the field of child development, introducing radically different and effective research methods, understanding and elucidating the development of children, influencing public policy with respect to “special education,” reforming the whole approach of medical pediatrics and helping to pioneer the larger field of human development. Along the way, he popularized his insightful findings and theories, which influenced generations of parents in their raising of children. His work was translated into 20 languages. But as is usual with pioneers, his achievements would subsequently be accompanied by some controversy.

From 1915 to 1919, while teaching at Yale, Gesell also served as director of child hygiene for the Connecticut State Board of Education. In that capacity, Gesell “formalized what would become the first position titled school psychologist’ in the United States.” Then, working with another talented psychologist, Norma Cutts in New Haven, “his efforts led to the creation of special education classrooms” and an interestingly titled Division for Educationally Exceptional Children under the auspices of the State Board of Education.

Not surprisingly, Gesell faced the challenge of understanding what “normal” development was in order to understand what departs from it. For that reason, he embarked on elaborate research into young children’s growth and development. Gesell was the first to use film, in extensive and influential ways, to study children’s behavior. This allowed researchers to observe behaviors repeatedly and to subject their observations to the scrutiny of one another and against other filmed “tests.” He also pioneered what is called “the co-twin” technique, to study the impact of learning, or environment, and heredity on twins who had matured in separate households.

Out of their elaborate studies, Gesell and his research team established norms for infant and child development, resulting in standards for evaluating both normal and abnormal development. Gesell identified 34 stages of development between birth and age 10, which led to the field of developmental testing to determine if a particular child was with, ahead, or behind growth norms. The impact of these studies and findings was of enormous consequence. One example may be seen by what resulted from Gesell’s persuasive argument that pediatricians needed to monitor development as well as treat disease. In 1935, the American Board of Pediatrics established the field of growth and development as a basic requirement for certification, “acknowledging the importance of developmental principles for preventive medicine” —this at a time when the notion of preventive medicine was barely conceived.

Gesell set out to achieve a goal rarely aspired to by serious scientists: He wanted to have a beneficial impact on the way children are raised by their families, and on children’s nursery school, kindergarten and elementary school experiences. With the assistance of other members of his research team, he wrote popularized versions of his findings on child development. It may be argued whether he liberated parents from undue concern about their children’s behaviors at different stages of growth, or caused them additional worry when their children appeared “out of the norm,” but there is no doubt of the impact he had on decades of parenting or of the path he paved for other popularizers like Benjamin Spock.

There were complications in Gesell’s thought that were never resolved in the minds of some of his critics. And Gesell seems not to have been terribly interested in responding directly to his doubters. To some critics, by stressing “normal stages of development,” he seemed not to value a child’s individuality. In fact, he most earnestly did. What the critics appeared not to understand was that, for Gesell, the particular child’s individuality was rooted in heredity and something he called “constitution.” Gesell did much of his research and writing during a period when psychologists were emphasizing environmental influences far more than hereditary factors as conditioners of a child’s development. Gesell advanced what he called a “theory of maturation,” in which heredity and environment were an inextricably interactive bundle. Environment, or learning, was crucial to him because true “maturation” meant the highest fulfillment of each individual child’s, inherited, innate and varied capacities. To help a child toward maturation, there needed to be an openness to each child’s distinctiveness. (It is worth noting that Gesell never came close to succumbing to eugenics, as his friend Lewis Terman did.) There was also, in Gesell, as there was in numbers of his Clark graduate student peers from the Hall years, a concept of the teacher-researcher and the parent-researcher-adults self-consciously attempting to understand, and then to respond to and cultivate, the distinctive capacities of each child.

It might even be said that Gesell’s interest in being a popularizer diminished him over time in the community of “pure scholars.” That certainly was the case at Yale University itself. This may be seen as an issue endemic to Clark pioneers, who persistently sought to join research with practice. Yet, the fact remains that Gesell made ground-breaking contributions to the general field of human development—bringing together anthropology, evolutionary studies, linguistics, biology, comparative psychology, embryology, neurophysiology and medical science. It remains a towering achievement.