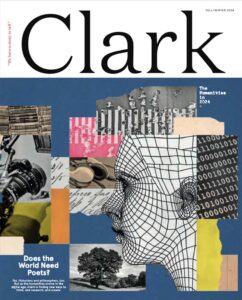

Amid technological advances like ChatGPT and other artificial intelligence tools, Clark’s faculty are examining how to prepare students for a fast-changing world while empowering them to move about in that same world with confidence, with empathy, and as critical thinkers. As humanists.

“It’s an exciting time. As someone who is interested in technology and sci-fi, I think, ‘Well, here comes the future.’ And it’s coming at us really quick,” says JOHN MAGEE, dean of the college and professor of computer science.

Yet some remain anxious, he acknowledges. “The concerns are, are we going to delegate some of what it means to be human over to AI and to computers? And if we do that, are we going to lose out both individually and societally?”

The world has faced technological disruptions before that have reshaped society, Magee points out, from the printing press to the personal computer to the internet.

Around 2012, Magee’s area of research—computer vision, AI, and machine learning—began to dominate the computer science field.

It then took more than a decade—and the release of ChatGPT to the public—for most educational institutions to wake up and realize the potential impacts of large language learning models on the curriculum. The notion of artificial intelligence “writing” fully formed books, articles, and, yes, college papers, has sent a chill through academia.

“What I find interesting is that this moment gives us the opportunity to question” how we teach students at Clark, Magee says. “We need to look at where we can have meaningful impacts. What should we be doing that still allows us to contribute to society in meaningful ways?”

As a longtime consumer of post-apocalyptic fiction, Magee sees parallels in how higher education might approach the use of AI.

“The potential dystopian future in higher education is this: Students write AI-generated essays and turn them in, and then professors use AI grading to grade them,” he says. “If we get to that point, we’re too late. We cannot turn over human cognition to the machines.”

“WE CANNOT TURN OVER HUMAN COGNITION TO THE MACHINES.”

To integrate AI and any other technological advances, Clark could reconsider student learning outcomes, Magee says. “What can students do that can be possibly augmented by those tools, not replaced by the tools? How do we ensure that students can still analyze a piece of literature or create art or describe what art is?

“You can still pose an intellectual problem as a human, and if you figure out how to use a particular tool, it might allow you to be more effective in solving that problem,” he notes. “Computer scientists recognize that the most interesting problems are not computational but societal. Understanding the world’s problems from a humanities perspective is vitally important.” ▣