This story ran in the spring 2006 issue of Clark News.

Devastating Flood No Match for Alumni Journalists

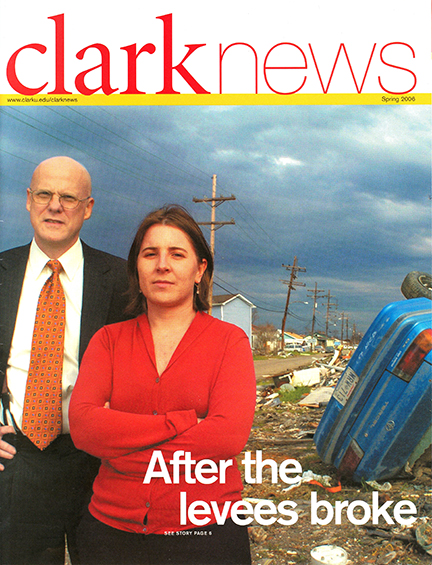

Dan Shea ’81 and Laura Maggi ’95 helped the New Orleans Times-Picayune keep publishing when it was needed most

On Tuesday, Aug. 30, 2005—the day after Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast and the levees in New Orleans failed—the New Orleans Times-Picayune used a one-word headline to describe the situation

‘Catastrophic’

But even as the city sank into chaos and disaster, the Times-Picayune continued to publish. The flood waters, it turned out, were no match for this Pulitzer Prize-winning newspaper, its Managing Editor for News, Dan Shea ’81, and the crew of reporters, photographers and editors who covered the event.

“For a hometown newspaper that has never stopped publishing, the thought of not publishing on my watch—it just wasn’t going to happen,” says Shea, who is responsible for all aspects of the production and presentation of the Times-Picayune. He has lived in New Orleans for 13 years and had weathered three major hurricanes before Katrina. The days leading up to the storm didn’t seem different from past hurricanes, Shea says, but by the end of the day on Friday, Aug. 26, the forecast took a turn for the worse.

“By Saturday, it was obvious that the city was going to be in serious trouble.”

‘The game was over’ Shea’s wife, Stephanie, who is also an editor at the Times-Picayune, and their two children evacuated the city to stay with Shea’s former Clark roommate, Jim Hamilton ’81, in Alabama. With his family out of harm’s way, Shea turned his attention to the newspaper. He and other editors put together a crew to work in the newspaper’s bunker, which has a generator, DSL lines and other equipment that would allow them to at least publish on the newspaper’s website, www.nola.com. The Times-Picayune published on Sunday, Aug. 28, and Monday, Aug. 29, although by then there was no way to deliver the Monday edition, Shea notes. Early Monday morning, just as the staff began to report on the storm’s arrival, the newspaper lost power. Shea remembers looking out the window.

“I’d never seen a storm that bad in the area, but it wasn’t a catastrophic storm.

By noon, the storm was lifting, and by 2 p.m., four teams of photographers and reporters were dispatched in TP trucks to cover the story. They returned almost immediately, saying water was blocking their path. Shea thought the drivers just didn’t want to take the brand new trucks out, so he and Editor Jim Amoss decided to go themselves.

“We knew right away that something was very wrong in the city,” Shea says. From models developed by Louisiana State University, he says, they expected flooding in the eastern part of New Orleans. But there was too much water coming right up to the newspaper building, just outside of town.

“I knew at that point that the game was over,” Shea says.

Other photographers and reporters ventured out into the city and they all came back with the same conclusion: the levees breached, and nothing would stop all of Lake Pontchatrain from filling up the bowl of the city, which lies up to 15-feet below sea level. While national media were reporting from the dry French Quarter that the city had “dodged a bullet,” the Picayune prepared a harrowing front-page account of the inundation for the Tuesday edition.

Early Tuesday, with the water now lapping at the entrance to the building and knowing that they could be trapped for days or weeks, Shea and his colleagues ran through the building grabbing whatever laptops and equipment they could carry. Thirty-five minutes later, they were all on 14 trucks, heading for higher ground. It took 45 minutes crawling though four feet of water to get to the interstate, which runs right in front of the building.

Out of danger, back in print “Once we got on the highway, I knew we had to publish a paper the next day,” Shea says. “It’s in the genetic code of journalists. This was the biggest story in the history of New Orleans. You want to be there.”

Twelve staff members went to a New York Times-owned newspaper in Houma, La., and 12 others volunteered to go back into the city to cover the story. They were able to get a text message to Newhouse News Service, which owns the Times-Picayune, and by 1 a.m. Tuesday, Aug. 30, reporters were updating the blog on nola.com.

Working with limited equipment and without the necessary production tools, Shea and his team pulled together a PDF of the Wednesday paper and posted it to the website. They moved go Baton Rouge the next day and published another PDF edition. On Friday, Sept. 2, the Times-Picayune was printed again, the copies taken to areas shelters where they were snatched up.

“People were rushing to grab copies of the paper,” Shea says, noting the value of the hometown newspaper in times of crisis. New Orleans has its problems, he notes, and the Times-Picayune “tries to be a voice of sanity and reason and progress.”

From the capital bureau For six weeks after Hurricane Katrina, the Times-Picayune operated out of rented space in Baton Rouge, where Laura Maggi ’95 covers the capital for the newspaper. During and after the hurricane, she camped out at the state Office of Emergency Preparedness trying to unravel the aftermath of the storm.

In the first few days after the hurricane and flooding, Maggi says the biggest challenge was trying to figure out the relationship between the state and federal government and “who was responsible for what.” She notes that the breakdown of the communication infrastructure due to the storm was a big hindrance. She also noted a “certain amount of spin coming from different groups” about what was or wasn’t happening to help victims, which only further complicated the issue as she witnessed the unfolding controversy surrounding former FEMA Director Michael Brown and Homeland Security chief Michael Chertoff.

“There were people in despicable situations who needed real help in real time,” says Maggi, adding that the storm brought new intensity to her work.

“Everything was heightened,” she says. “You had to act more quickly, and it was more important. There were people all over the South reading the Times-Picayune to learn about their loved ones.”

Maggi also gained a deeper understanding of the value of her work as a reporter.

“When I write an article that has to do with plans to get people back into their homes, I know that I matters to people,” Maggi says. “And holding officials accountable for their actions is a good thing to do.”

Far from normal While it has remained the focus of national attention and congressional investigations, the immediacy of Hurricane Katrina, the flood and the plight of its victims has faded over time for most of the country. But it hasn’t fades at all for those left living in New Orleans and the surrounding region. In Baton Rouge, Maggi says the city has shrunk slightly since the evacuation from New Orleans, but its still unclear how many people plan to stay permanently. In New Orleans, Shea sees a situation that is much more complicated than what the rest of the country sees on the news. Parts of the city were untouched by the flood, he says, and most of the suburban parishes are in “great shape.”

Other parts of the city, however, are devastated. Shea and his family live in Jefferson Parish, in the one neighborhood there that was flooded. The first floor of his house is gutted, and all the vegetation outside is dead. He and his family are back living on the second floor of their home, using the FEMA trailer in their yard as a kitchen and living room. Many people who were flooded out aren’t back yet, She adds, and about one third of the newspaper staff is still out of their homes. Shea praised Newhouse News for taking great care of the Times-Picayune staff. Not only had no one been laid off, Shea says, everyone received a raise in December.

Even though parts of New Orleans survived the flooding and rebuilding had begun, Shea says life is far from normal.

“In certain ways, it’s the late 1950s again. You don’t go out casually to find some fast food, or gas or milk. Things close early. And there’s never a routine day at home.”

However Shea stressed that the damage had little to do with the hurricane itself.

“Hurricane Katrina did not do this to the city,” he says. “It was the levees breaking as if they were made of papier maché.”

Thinking on your feet A Worcester native, Shea says Clark has been a source of moral support during this crisis. A Clarkie provided shelter to his family and many alumni have contacted him since the storm. Shea also credits his Clark educations with helping him keep the Times-Picayune running when it was needed most.

“Clark encourages you to think on your feet, and we had to do a lot of that in the storm.”