How students and faculty breathed new life into Clark’s urban forest

Over several weeks, Kasyan Green ’21, M.S./GIS ’22, Natalie Hanna ’23, and Alexander Frasher ’23 pulled weeds, raked leaves, and laid down mulch, carefully sculpting a three-foot-wide path that hugs the hillside and winds through cucumber magnolia, black walnut, gingko, bald cypress, fernleaf birch, and dozens of other century-old trees planted by dairy farmer Obadiah Hadwen.

One day in 2023, while working on the trail, Green noticed a small puddle.

“It’s unusual to see a puddle in a forest—usually that water would disappear,” he recalls thinking. “We pulled away the leaves, and we could see water bubbling up. We found a beautiful little spring was hiding there all along.”

The aptly named Hidden Spring Trail now connects with several other paths crisscrossing the Hadwen Arboretum, owned by Clark since 1907, when Obadiah died at age 83 and bequeathed the University his family’s 18-acre Magnolia Farm. The parcel included more than 1,000 trees—around 100 varieties—declared the “finest collection of trees, native and exotic, that exists in New England” by a botanist that Clark commissioned to survey the site. In 1931, Hadwen’s daughter, Amie Hadwen Coes, donated more land, expanding the Arboretum to 26 acres.

hadwen history_01

In the 64 years that he owned Magnolia Farm, Obadiah Hadwen planted more than 1,000 trees, including the Scottish poplar, Kentucky coffee, Japanese gingko, Chinese cork, apple and pear, and 15 species of his beloved magnolias.

Like that hidden spring, the Arboretum has yielded many discoveries over the past four years as a rotating crew of Clark students, working alongside Geography Professor John Rogan, has hacked through a jungle of climbing bittersweet vines, pulled invasive knotweed and poison ivy, and cleared dead branches to recover once-ailing trees.

“I introduced the students to the Arboretum and provided them with the resources, but then I really let them do their own thing, and good things have come from it,” Rogan says.

Through Rogan’s classes, the Arboretum Advocates club, and Clark’s Human-Environment Regional Observatory (HERO) research program, nearly 100 Clark students have revitalized this hilly green space at May and Lovell streets, in the Columbus Park neighborhood. Their goal is to make the Arboretum more inviting and accessible so scholars and schoolchildren alike can enjoy and study it up close.

hadwen history_02

For the first decade after Hadwen’s death in 1907, Clark employed a full-time caretaker to manage the property. The University grew produce there for its cafeterias.

To tackle this monumental project, Rogan’s urban forestry class in 2019 used the tools of geographic information science to inventory and map nearly 70 tree species and develop a management plan for the Arboretum. Green delved into its history with Anna Bebbington, M.S./GIS ’22, and Juliette Gale ’20, M.S./GIS ’21, “gaining a deeper understanding of what the space was, what it is now, and what it could be in the future,” he says. They created a digital timeline and content for a Clark Arboretum website.

hadwen history_03

In 1925, Biology Professor David Potter outlined to President Wallace Atwood how best to manage the Arboretum “for the educational benefit of the University”: clear dead trees and brush; identify, label, and catalog trees and plants; plant new specimens; and take soil samples. Atwood, no fan of the previous caretaker and loath to hire a new one, essentially told Potter, “The job is yours.”

Rogan first imagined the Arboretum’s potential in 2018, when then-City Councilor Matt Wally, M.A./CDP ’06, reached out. Rogan was known around Worcester as a tree lover. Every summer, a cohort of students in the HERO program—which he manages with Geography Professor Deborah Martin—researches the impact of stressors like invasive insects, climate change, and human activity on urban trees.

Accompanied by Jack Foley, then Clark’s vice president of government and community affairs, Rogan and Martin met with Wally, who described the Arboretum as a tangled mess, overgrown with invasive plants and riddled with trash. To the neighbors, it felt unsafe and unwelcoming.

Around the same time, Anthony Himmelberger ’19, M.S./GIS ’20, shared a research paper with Rogan. Active in the Arboretum Advocates, the earth system science major had researched the area’s history and surveyed and mapped over 300 trees there. For help, he recruited Galen Oettel ’21, M.S./GIS ‘22, an environmental science major with a knack for identifying species.

“I was passionate about the space and hoped that someday it would get the attention it deserved,” Himmelberger says. “It was just good timing. Everything kind of happened at once.”

hadwen history_04

Potter did the best he could with Clark’s limited resources. Starting with its founding in 1931, he led the Hadwen Botanical Club, which collected thousands of specimens of plant life, that were later donated or sold.

“When John got involved, that was a game changer,” recalls Oettel, who, in his first year at Clark in 2017, joined Himmelberger in Arboretum Advocates, which held occasional cleanups and hikes. “John could do so many things that we couldn’t do with the club. Once John started, we had a consistent team of people working there multiple times a week.”

Rogan recalls a key turning point: Arbor Day in April 2019, when he and the students joined Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) employees to clear dead trees, bag trash, and hack through vines and knotweed.

“When I saw that sort of collective action, and how nice the site looked, I thought we should do more of this,” he recalls. “That’s when I started doing the work here, and I haven’t looked back.”

Over time, Rogan and his students have strategically selected and planted more trees, established a mile of new trails with the help of Clark’s Facilities Management crews, erected wayfinding signs, split fallen trees to craft benches, and created an outdoor classroom now used by local schools.

Nicholas Geron, Ph.D. ’23, was involved with the project from the beginning as a teaching assistant for Rogan’s classes and the HERO program. He’s now an assistant professor of geography at Salem State University.

hadwen history_05

During World War II, as an act of patriotism (and agriculture), the Clark University Board of Trustees voted to allow the planting of a community Victory Garden in the Arboretum.

“It was just completely revolutionary in terms of what education could be,” Geron says. “One day you could be clearing a trail, and the next day you could be mapping invasive species or doing tree identification. It opened my mind to how higher education can interact with the surrounding environment and local community. Seeing John’s persistence and continued investment is really inspiring.”

To guide the ongoing project, Rogan has tapped into a network of advisors from Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum, the DCR, Worcester Tree Initiative, New England Botanic Garden at Tower Hill, and the Greater Worcester Land Trust. Last summer, the Worcester Native Plant Initiative planted a pollinator garden near the May Street entrance.

“It’s usually a two-way interaction where we learn something from these people, and they learn something from us,” he says.

The Clark team first cleared a trail that brings people into the heart of the Arboretum. It follows abandoned Appleton Road, which once led up the hill to Fairlawn Hospital and provided access to the Hadwen family’s farmhouse, fruit orchard, and plant nursery. Near the bottom of the trail, Green rebuilt the stone wall that would have welcomed guests to Hadwen’s farm amid hostas and other perennials planted long ago.

hadwen history_06

A Clark professor studied animal behavior at the Hadwen Arboretum, apparently using a shed to harbor two alligators and a porcupine “trained to do a number of tricks and stunts.” The porcupine escaped; the reptiles didn’t survive the winter.

“A part of me would have just loved to stay there forever because I really love the Arboretum,” says Green, who continued working in the Arboretum for six months after graduating from Clark. “It felt very much like a sanctuary for me.”

The Arboretum has evolved into a community resource—long unnoticed, even by neighbors, it is now a source of pride. Residents walk the leafy trails. Hikers cut through the space, which is part of Worcester’s 14-mile East-West Trail, headed to and from abutting Coes Reservoir. Others maintain plots in a community garden at the top of the hill.

For 20 years, Daria Meshenuk ’72 lived a half mile away, yet she didn’t know the Arboretum existed until three years ago. She now exercises there regularly, running into Rogan as he’s pulling weeds or watering newly planted trees.

“I was very impressed by John’s vision for the place and how he so comfortably and easily involves other people,” Meshenuk says. “He cares about making the world a better place and has the tools needed to work constructively and bring people together.”

Rogan envisions turning the Arboretum into a living, working laboratory where Clark researchers can study the effects of global climate change at the local level—an effort that aligns with the University’s goal of launching a school for climate studies. Ideally, that would include staff responsible for maintaining the space, with an electric-powered central building and water hookups for year-round education and property management.

hadwen history_07

A Clark group studying uses for the property once proposed building dormitories there.

“If a university anywhere were really conscious about climate change and community engagement, such a university would want a green space to facilitate that—to do experimentation and to engage the community,” Rogan points out. “And we already have that. The Arboretum has remained this hidden jewel, and there are a lot of interesting things already going on there. In 10 years, it could be all that we’re hoping for.”

Clark faculty and students, he notes, already are tapping into the Arboretum for research and coursework.

Biology Professor Kaitlyn Mathis’ classes head there to observe the interactions between plants and insects. “The Arboretum is a fantastic resource because it’s within walking distance to campus, and we’re able to collect samples of a wide range of insects,” says Mathis, who researches the ecology of ants in managed ecosystems.

Her colleague, Professor Erin McCollough, was excited to find a nearby thriving ecosystem where she could collect dung beetles as part of her investigation into their mating habits.

hadwen history_08

Clark fielded two significant purchase offers for the property: from the City of Worcester, who sought to build a new high school there, and from nearby Fairlawn Hospital. In 1985, the Board of Trustees made the firm decision not to sell the property.

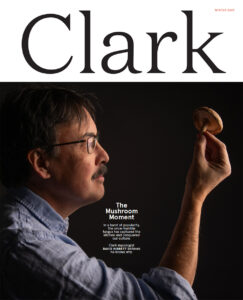

Professor David Hibbett, an eminent mycologist, regularly brings students into the Hadwen to conduct research on local fungi.

Professor Morgan Ruelle and students from the Department of Sustainability and Social Justice head to the Arboretum to observe seasonal changes, informing their broader study of humans’ connections to place and the environment.

Two years ago, Ruelle’s graduate research assistant, Evan Collins, M.S./ES&P ’21, researched bats for his master’s thesis with the help of Duncan Drapeau ’21, M.S./ES&P ’22. They compared bat activity and species diversity in the Arboretum with that of nearby Coes Reservoir and Mass Audubon’s Broad Meadow Brook Wildlife Sanctuary. “One night at the Arboretum, we had near constant activity of bats, more than any of the other sites we checked,” Collins recalls.

Ruelle hopes to set up acoustic stations to capture more data about the bats frequenting the Arboretum. This year, he plans to set up low-cost weather stations to monitor precipitation and temperature so students can research the impact of climate change locally, while testing out the equipment for use by indigenous communities globally.

When students are gone for the summer, Rogan can be found working in the Hadwen Arboretum several times a week. In heatwaves and drought—like the one in summer 2022—he hauls water from his house in gallon jugs to care for newly planted trees.

“He goes about his work very quietly,” Kas Green says. “There have been times when I’ve been in the Arboretum, building a trail or taking ivy off the trees, and as I’m leaving, I’ll see that John was there the whole time as well.”

The place is a respite from the frantic city energy surrounding it, perhaps more so for those who have shaped the paths leading into the heart of Obadiah Hadwen’s gift to Clark, and shared a vision for what it could become.

PHOTOGRAPHS BY STEVEN KING