Clarkives

George Blakesee was a pioneer in the international relations field

Excerpted from “Changing the World: Clark University’s Pioneering People, 1887–2000” (Chandler House Press, 2005), by Richard P. Traina, president of Clark University from 1984 to 2000.

In August 1951, on the occasion of George Blakeslee’s 80th birthday, Secretary of State Dean Acheson sent the retired Clark professor a congratulatory letter, in which he wrote: “Your abiding interest and close participation in foreign relations and the role of the United States in world affairs has left its indelible imprint on the course of events and on the colleagues with whom you have served so eminently over the years in the Department of State and in international organizations.” Acheson also referred to Blakeslee’s “distinguished academic work” in international relations —in which he was a far-reaching pioneer and major transitional figure.

In order to grasp the role Blakeslee played in reshaping the curriculum of higher education and establishing a role for academics in the making of the nation’s foreign policy, it is important to recognize that international relations was not a field of study in the early 20th Century. Even the study of non-Western cultures was not a part of college or university curricula. The subject of history was basically limited to the United States and Western and, to some extent, Central Europe. As a result of that educational posture, leaders of American society shared the attitude that Western culture was superior to all other “alien” cultures.

Blakeslee was a pioneer, not only in bringing serious study of other cultures and of international relations into higher education at both the undergraduate and graduate levels, but in attempting to educate the American public, understand public opinion about foreign affairs and help shape American foreign policy through the influence of academic study. Even while he never fully shed the cultural and racial biases so commonly held by his contemporaries in responsible positions, Blakeslee was a significant transitional figure-rejecting an attitude of exploitative superiority over “backward” peoples and adopting, in its place, a kind of noblesse oblige. This son of a Congregational minister was committed to the idea that education, mutual understanding, and negotiation were always preferable to the use of force. “Race-child” peoples could be cultivated to maturity. The efficacy of democracy and the benefits of the free market were his twin convictions. Blakeslee’s appreciation of valuable and laudatory cultural distinctions in the history and practices of non-Western nations never quite reached an attitude of parity but he seemed always to be moving in that direction.

Before arriving at Clark as a young professor in 1903, Blakeslee received a bachelor’s degree from Wesleyan University and master’s and doctoral degrees in history from Harvard University. He also studied at Johns Hopkins and at the universities of Berlin, Leipzig and Oxford. And even while he had a number of appointments at other prestigious institutions during the interwar years, Blakeslee remained a member of the Clark faculty until 1944. Toward the end of World War II, he devoted himself to his responsibilities at the Department of State, to which he had given periodic service since 1920.

On Blakeslee’s recommendation, Clark University early established a department of history and international relations. As a consequence, before World War I, courses for undergraduates were being offered that treated Russia, Liberia, Manchuria, Japan, China, Turkey, Siberia, the Philippines, and the Congo Free State. During the same period, graduate courses were being taught on Russia and the Far East, the Near East and Africa, British colonies and dependencies, and Latin America, soon followed by courses on diplomacy. Clark’s first doctoral degree in “history and international relations” was awarded in 1916. By the 1920s and 1930s, international studies were offered prominently at a number of universities, including Georgetown, Johns Hopkins, Tufts, Stanford, Michigan, and Chicago.

While he led the reform of curriculum, Blakeslee also established the first scholarly journal of international relations, the Journal of Race Relations, subsequently renamed the Journal of International Relations. He also helped form the Council on Foreign Relations, which remains an important and influential citizen organization. Meanwhile, beginning in 1910, Blakeslee prompted G. Stanley Hall to approve what became a ground-breaking series of six conferences on international relations — each one attracting large numbers of eminent government officials, businesspeople, commentators, academics, admirals and generals, foundation officials, and leaders of international organizations.

Frequently controversial, these conferences covered a wide range of issues, and each resulted in a volume of learned essays, some 200 in all, including “China and the Far East”; “Japan and Japanese-American Relations”; “Recent Developments in China”; “Latin America”; “Problems and Lessons of the War” (published in 1916, prior to the United States’ entry into World War I); and “Mexico and the Caribbean.”

As was to be the case with so many of the achievements of Clark’s pioneers, inadequate funds resulted in others taking over the Journal of International Relations, which became the Foreign Affairs Quarterly. Blakeslee continued to help edit the journal. Likewise, an inability to continue funding the conferences meant that they moved to the Williamstown Summer Institute of World Politics, again with Blakeslee’s assistance.

It is difficult to imagine how a single individual could accomplish so much and with so little assistance. His description of his initial decade or so at Clark is evocative: The “early days were a thrilling experience: a small, young faculty; a small, able student body; plenty of academic freedom and intellectual initiative. We all worked hard; we had to; each of us had not a Clark chair, but a settee.” Even so, Blakeslee managed regular tennis games (at which he had great talent), less frequent baseball games, and occasional adventures.

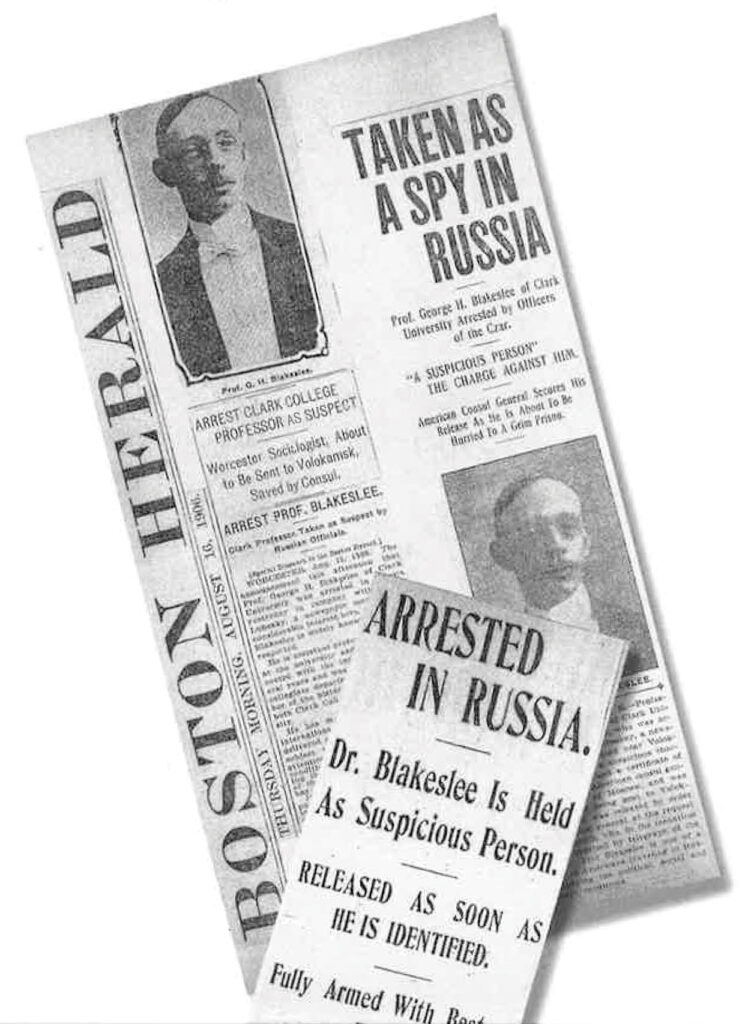

His most notably hazardous trek was taken with his wife to Czarist Russia in 1906, during which he narrowly escaped being blown up, when a bomb destroyed the house of the Russian premier. Subsequently, Blakeslee was arrested in Russia on suspicion of being a spy — having traveled the country with radical leaders, meeting rebellious peasants, and being accused of distributing a revolutionary manifesto. After the intervention of the American Consul General, the Governor of Moscow released Blakeslee.

His most notably hazardous trek was taken with his wife to Czarist Russia in 1906, during which he narrowly escaped being blown up, when a bomb destroyed the house of the Russian premier. Subsequently, Blakeslee was arrested in Russia on suspicion of being a spy — having traveled the country with radical leaders, meeting rebellious peasants, and being accused of distributing a revolutionary manifesto. After the intervention of the American Consul General, the Governor of Moscow released Blakeslee.

The six major international conferences that Blakeslee organized at Clark between 1910 and 1916 ultimately resulted in the recognition of his talents by officials in Washington. He had, for every one of those conferences, attracted large numbers of prominent figures and public officials as participants, and as a consequence he became widely known and appreciated. Blakeslee helped set in motion the practice by the Department of State of using academic experts in the formulation and conduct of foreign policy.

Toward the end of World War I, Blakeslee served Woodrow Wilson’s administration on matters related to the Pacific Islands. In 1921 and 1922, he was a technical adviser for Warren G. Harding’s Secretary of State, Charles Evans Hughes, at the Washington Conference, which reduced naval armaments and contributed to peace in Asia for the next decade. In 1931 and 1932, Blakeslee served under Herbert Hoover’s Secretary of State, Henry Stimson, on the Lytton Commission, concerning Japan’s seizure of Manchuria. (According to a story later told by a member of the Japanese royal family, Blakeslee and others on the Commission survived an attempted poisoning during their 1931 Manchurian trip.)

During World War II, he was first a consultant to and then officer in the Far Eastern Division of the State Department, finally serving as political adviser to the Far Eastern Commission, which shaped policies in occupied Japan from 1945 to 1952. In fact, a substantial percentage of the people working the Asian desk in the State Department at that time had been trained by Blakeslee. By his last decade of service, under Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman, Blakeslee had served in important capacities under five different presidents.

This was a remarkable career, both for the breadth of the contribution and the longevity of earnest, dedicated service — not to mention the ground-breaking character of much of what he accomplished. Never fully rising above the cultural and racial attitudes of his age and class, Blakeslee’s practical idealism nonetheless advanced the American people’s understanding of other cultures and the enduring hope for a peaceful world. Described as an “action-intellectual,” he clearly stands in the center of that Clark University tradition.