A family, a gift, and a decades-long love for Clark

Blossom Brooks liked nothing more than a good adventure.

Undeterred, Blossom continued her Berlin studies, went on to enjoy a long career teaching German and French at East Stroudsburg University in Pennsylvania, and traveled the world — right up until her death last year at age 86. After graduating from Clark in 1953, she studied in Berlin as tensions within the city were escalating. Daily, she passed through “Checkpoint Charlie,” the most-trafficked crossing point between West and East Berlin. One day, as she was walking to the West after a violin lesson, a Stasi security officer confiscated her camera, ripped out the film, and crushed the camera beneath his boot.

If adventure was a strand of Blossom Brooks’ DNA, so was Clark University. Her mother, Rose Brooks, worked for many years in Clark Admissions. Blossom’s sister, Harriet Brooks Dietz ’48, M.A. ’50, and brother, Marvin Brooks ’52, were Clark alums. Her other sister, Elaine, did not attend Clark, but Elaine’s husband, Alan Elbein ’54, did.

The Brooks family was so devoted to Clark that Rose, Harriet, Marvin, and Blossom stipulated that their individual estates be put in a joint trust for Clark University. When Blossom died on March 9, 2017, Clark became the sole beneficiary of the trust — a $4.5 million gift.

Elaine’s son, Richard Elbein, recalls a tightly knit band of siblings who were ardent musicians, playing in local symphonies (including at Clark). They inherited their work ethic from their parents, Rose and Michael, European immigrants who owned a dairy and bottling plant in Worcester and who insisted their children receive a college education.

“For them, education was everything,” Elbein says. “They felt it was the transformative force in their immigrant experience that allowed them to arrive in this country with nothing and have four successful children.”

Elbein was raised in Texas but spent summers in Worcester, where he came to know his extended family. Harriet, who taught and later worked as an assistant high school principal in Hollywood, Florida, was “very particular.”

“Everything had its place. You were expected to dress appropriately, speak appropriately, and act properly. That was very much a Brooks family thing,” he says.

Harriet married twice but never had children (neither Marvin nor Blossom married). She died of ovarian cancer in 1995 at the age of 66. In a newspaper story following her death, Harriet was remembered as a “tough but fair” administrator with a reputation for “apprehending wandering students — even if she had to run them down — during hallway patrol.”

“She was everywhere,” a former student recalled. “She was always known for her big sneakers. She was a tough cookie.”

Marvin Brooks was a private person, fastidious, “very much the engineer,” Elbein says. He worked for the coal division in the U.S. Department of Energy. While negotiating with coal producers in West Virginia, he stepped onto the second-floor walkway of his motel, slipped on ice, and tumbled down a flight of stairs. The impact severed his spine, leaving him a quadriplegic for the remaining 10 years of his life. He spent his last decade in a skilled nursing facility in Pennsylvania, where Blossom became a regular visitor. “She drove 45 minutes after work every day to take care of him,” Elbein says. Marvin died in 2012.

Blossom was her mother’s daughter through and through. “Blossom and Rose both had a big sense of humor,” Elbein says. “They were true characters. Blossom was a very funny woman.”

Blossom spent 28 years at East Stroudsburg University, and prior to that worked as a translator. Then Marvin died, Elbein moved her to Houston, where she lived in the same facility as her sister Elaine.

Every year, Blossom insisted on taking an international trip, even as she struggled with health issues that impaired her short-term memory and mobility. In 2016, Elbein accompanied his 84-year-old aunt on a pilgrimage to the Taj Mahal.

“She loved being around people and hearing their stories,” Elbein recalls. “We would visit temples, and when she’d get tired she would sit and rest. Before you knew it she would be surrounded by people — high-school-age students, people her own age. She’d be advising the kids how to apply for college in America; a teacher to the very end. It was like she was the matriarch of people she’d never met.”

Elbein marvels at the strength and longevity of his family’s Clark connection, which dates back to Rose’s employment in Admissions (he estimates her time there began before 1920). Rose, who died in 1991, saved everything, he says, including a cache of letters from students complaining about their roommates’ religious and political affiliations.

“Rose kept letters written between Clark and anybody,” he laughs. “There’s an entire archive of them.”

Clark was not notified in advance about the Brooks family bequest, Elbein says. It came as a surprise. But that’s simply how his aunts, uncle, and grandmother went about their business — with little fanfare and significant impact. An adventure on their own terms.

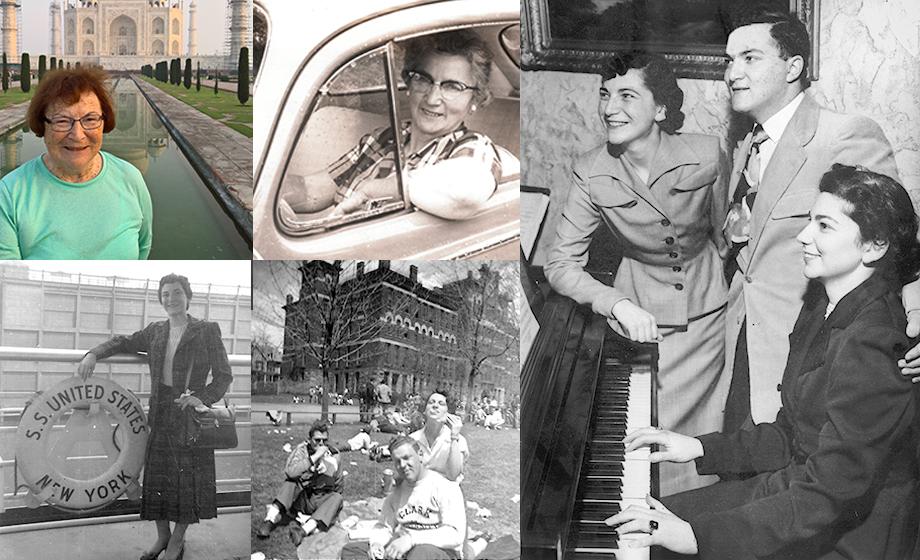

Pictured above, clockwise from top left: Blossom Brooks ’53 on her trip to the Taj Mahal; Rose Brooks takes the wheel; Blossom, Marvin Brooks ’52, and Harriet Brooks Dietz ’48, M.A. ’50, were always ready for an impromptu performance; Alan Elbein ’54 with Eleanor (Brooks) Elbein having fun at Clark; and Blossom boards a ship for the journey to Germany.

From Clark magazine, summer 2018