Clark Magazine

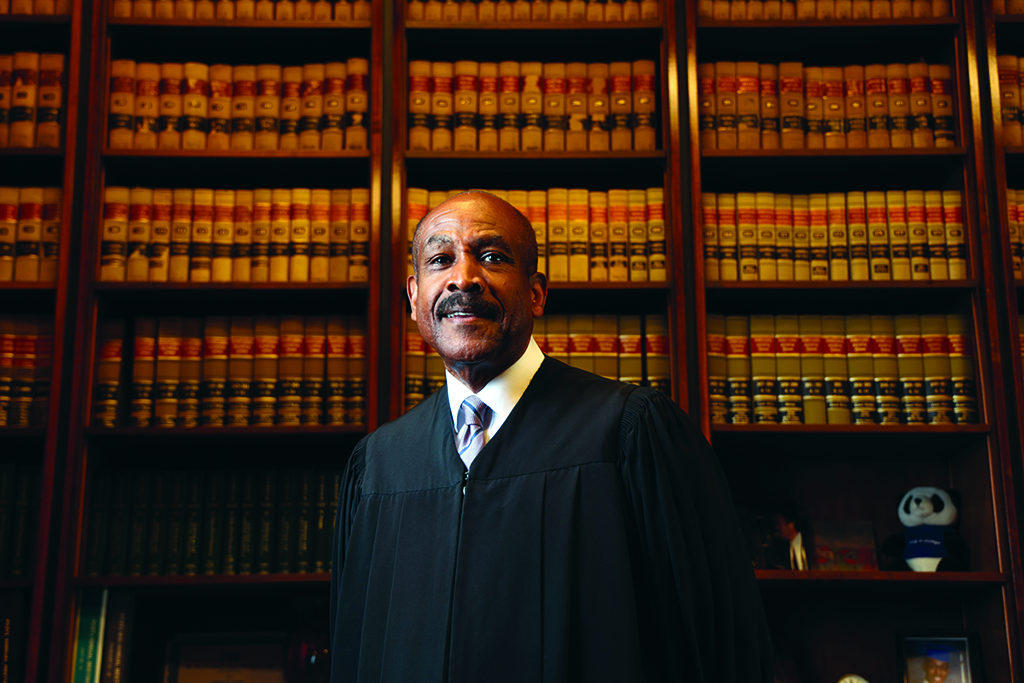

Guitar to gavel

From the bench in the Philadelphia County Court of Common Pleas, Judge George Overton ’76 renders decisions on legal matters that don’t make headlines but are indelible milestones in the lives of everyday people: the final resolution of a family member’s estate; the care and custody of someone incapacitated by illness or age; the adoption of a child.

The legal complexities and charged emotions surrounding these cases require Overton to balance compassion with objectivity.

“You have to submerge your personal feelings because everybody has personal beliefs or leanings,” he says. “But when you hear a case, you have to put those aside.”

There was a time, prior to establishing his reputation as an impartial jurist, when Overton did indeed express himself with flair and feeling, performing with the popular R&B group The Stylistics in front of thousands — from New York to New Zealand, San Francisco to Singapore.

How he got there is a Philadelphia story.

Since early childhood, music has always been a part of Overton’s life. He began playing piano at age 7, and for seven years studied classical piano before his parents gave him permission to switch to guitar.

Changing instruments was irresistible for young George. He grew up in Philadelphia in the 1960s during the advent of The Philadelphia Sound, characterized by funk influences and lush instrumental arrangements, often featuring sweeping strings and piercing horns. Across the street lived the young bass player for Patti LaBelle and Grover Washington. Amazing music was the neighborhood oxygen.

“They would be rehearsing outside during the summer, and we would hear the music. The guitar just kind of caught my ear,” Overton recalls. “Once I got to eighth grade, I switched instruments.”

His good friend Ed Moore, who lived around the corner, played guitar and became an important mentor. Overton began performing with several local groups, including one called Chromatic Funk, whose lead singer, Jimmy Williams, went on to become a recording artist with the group Double Exposure.

“I played during the summers all throughout college, and even when I was at Clark, I would sit in with a lot of the groups that would come through, just to keep my guitar skills up. I met a lot of great musicians who were very helpful in terms of sharing their craft — people like Larry Coryell, George Benson, and Earl Klugh.”

Overton came to Clark through a connection with his employer’s son, who encouraged him to look at schools in the Northeast. He initially majored in English before moving to political science and eventually earning a degree in sociology.

“I got a great education,” he says. “I was involved in student government, played some intramural sports, and actually did a short stint with the crew team. It was a wonderful, very enriching environment. I met a lot of good people, some of whom I maintain friendships with to this day.”

After graduation, Overton devoted himself to music. He toured the U.S. with a group called Blue Magic before joining the Philadelphia soul group The Stylistics, with whom he went on a six-month world tour in 1982. The Stylistics, who continue to perform today, formed in 1968 and surged in popularity in the 1970s with some of the most recognizable songs of the era. Their chart-topping odes to young love and heartache — like “You Make Me Feel Brand New,” “You Are Everything,” “Betcha by Golly, Wow,” and “I’m Stone in Love with You” — became touchstones for legions of fans.

Even in the early 1980s, with their biggest hits behind them, The Stylistics were a formidable band, and being on stage with them was heady stuff as the group toured throughout Asia, Australia, and Europe. But over time, the allure of the road waned for the Philly guitarist. “I think I knew all along that I wouldn’t perform for the rest of my life, although I knew I’d always play the guitar in some form or fashion. But touring allowed me to travel, see the world, and play some great music.”

Craving more stability in his life, Overton turned his attention to another aspiration he’d had since childhood: becoming a lawyer.

Just as music permeated his young life, so did the presence of “giants” in Philadelphia’s Black community — among them prominent lawyers — whom the young George had met through his father. Something about their distinguished bearing and their polish stirred in him a desire to maybe one day follow in their footsteps.

As an adult, interacting with lawyers and others on the business side of the music industry reignited Overton’s earlier dreams of pursuing a law career. He took prep courses, passed the LSAT, and applied to a few schools before enrolling at Delaware Law School at Widener University. “Actually, I was on the road when I found out I got accepted to Delaware,” he recalls. “I think I was in the Middle East at the time.”

During his first year of law school, he continued touring with The Stylistics.

“Wherever we’d be traveling, I would study en route. When I had downtime, I had the books with me. I just made it work,” Overton says. That level of discipline came naturally for someone who had practiced up to 10 hours a day to master the guitar. His fellow musicians, he notes, ultimately understood his desire for a career change. “In talking to the guys in the group, they certainly say it wasn’t a bad decision!” he laughs.

He officially left The Stylistics at the start of his second year of law school. It was around this same time that he married, and he and his wife, Nadine, went on to have two sons. After graduating, he entered private practice in the area of general civil litigation.

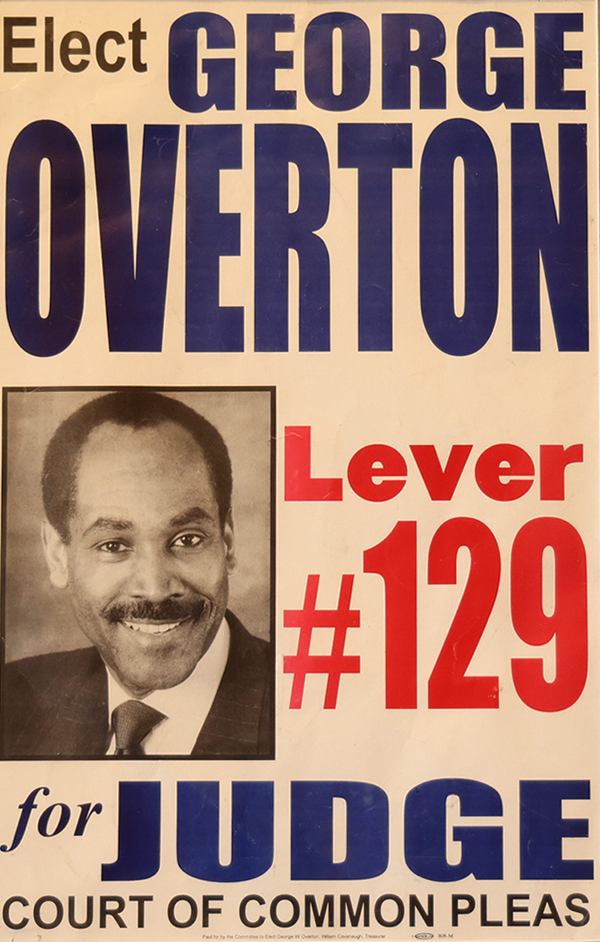

As his career progressed, Overton was resented with the prospect of a judgeship. When first approached about the possibility, he declined, saying he wanted to gain more experience and that he was enjoying the practice of law. Several years later, he was asked again. This time, he considered it more seriously.

As his career progressed, Overton was resented with the prospect of a judgeship. When first approached about the possibility, he declined, saying he wanted to gain more experience and that he was enjoying the practice of law. Several years later, he was asked again. This time, he considered it more seriously.

“I realized that I could bring the skills I had developed, the insight and the maturity, and I could be an asset to the bench,” he says. “Sometimes your focus is one way, but when opportunities present, you have to step out of your comfort zone.”

He hasn’t looked back. Since being elected to the bench in 2001, Overton has served in the criminal, civil, and family court divisions, and currently resides in “Orphans’ Court,” a division of the Court of Common Pleas, where he hears probate cases, nonprofit charitable matters, cases involving minors, and incapacity cases.

The work is not without its challenges. Overton cites the responsibility to “make decisions that may be at odds with how I personally feel about a particular matter, because the evidence may not support my particular beliefs.”

The greatest reward of the position? “Being able to serve the citizens of Philadelphia and citizens of this commonwealth,” he answers without hesitation. He also recently completed a term serving as president of the Pennsylvania Conference of State Trial Judges, where he represented more than 450 judicial colleagues.

“I’ve thoroughly enjoyed being a judge, because it allows me to exercise that part of my brain that is analytical and geared toward the law,” he says.

The transition from a law practice to the bench came with an unforeseen benefit: It opened up some space in his life to continue playing music. Overton jams with several informal bands composed of professionals from the law, medicine, academia, and business who want to continue indulging their love of performing music.

The judge has never had trouble finding a connection between music and the law. Each is about being part of something larger than yourself, he insists. Playing an instrument inspires camaraderie among musicians, and a judge is “the representative of a system and a process.”

“When I do things, I’m mindful of my representation of the court as a whole,” he says. “It’s not just an individual pursuit. When the judge comes into the courtroom and they say, ‘All stand,’ people are not standing for me — I’m standing, too. We’re standing for the system that we all represent.”

Of course, Overton and his fellow Stylistics also experienced standing ovations from thousands of fans expressing appreciation for their artistry.

“My friends from the music world and those from the legal world are often amazed that I’m able to meld the two,” he acknowledges. “But to me it just seemed like a natural transition, an evolution. You can’t have a world without music, and you can’t have a world without law. They both provide something that we can’t live without.”