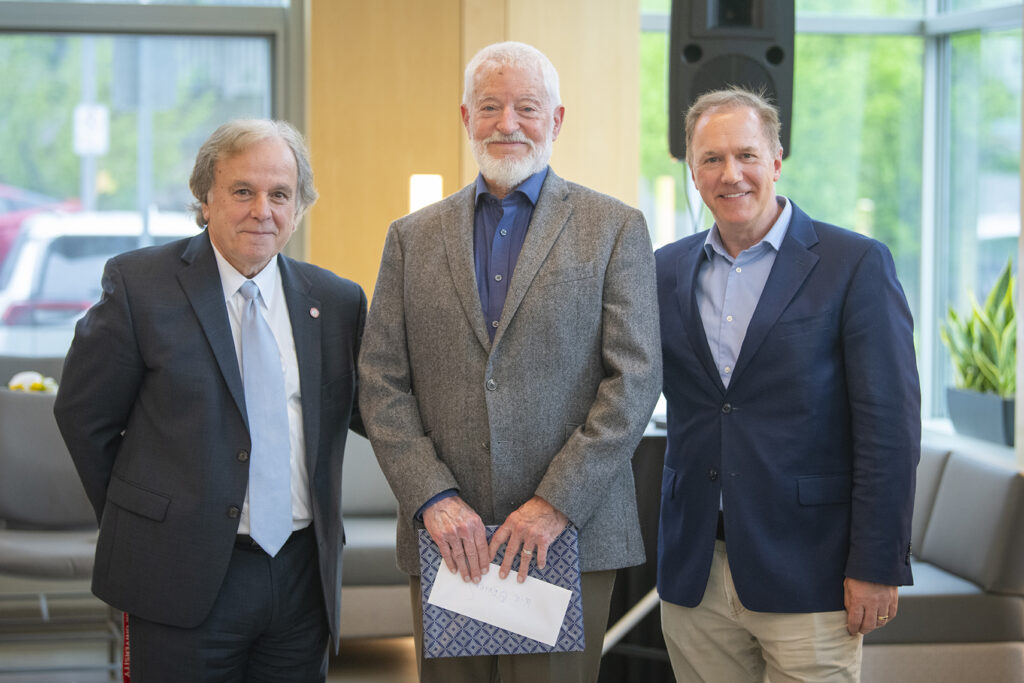

The May 6 retirement reception for Clark faculty offered an opportunity to honor, celebrate, and thank three individuals who collectively gave more than a century of service to the University.

Professors Patrick Derr (philosophy, 49 years), Wayne Gray (economics, 41 years), and Will O’Brien (School of Business, 16 years) were feted by their colleagues at an afternoon program held in the Alumni and Student Engagement Center.

President David Fithian lauded the honorees for their many years of distinguished service and noted that over their careers, they have balanced “continuity and innovation” in a way that has well served their students and the institution.

“We are indebted for all that you have done here,” he said.

Dean of the School of Business David Jordan recalled first meeting O’Brien in 2009. “I knew I could learn a great deal from him. About sustainability, scholarship, and about what it takes to be a stand-up man.”

O’Brien came to Clark with an impressive background in business and entrepreneurship, including emerging technologies. He brought a global and green perspective to the School of Business, playing an integral role in grounding the business curriculum in the principles of environmental sustainability and social responsibility — always with the caution that corporate allegiance must never supersede our human obligation.

“He brought passion and compassion,” Jordan said. “We will miss him immensely.”

In his remarks, Ravi Sharma, chair of the Department of Philosophy, read testimonials from two of Derr’s former students, who described a teacher who urged his students to grapple with some of the thorniest issues involving ethics, equity, environment, medicine, and the AIDS and COVID pandemics. One student described him as “possibly the greatest professor I have, or ever will have.” Another wrote of the formidable nature of Derr’s courses that examined biomedical and public health issues, including one that required the reading of a 600-page book before the class had even started — but the class “made me more concise and confident.” Derr’s Environmental Ethics course “fundamentally challenged, shaped, and grew my thinking,” the student added.

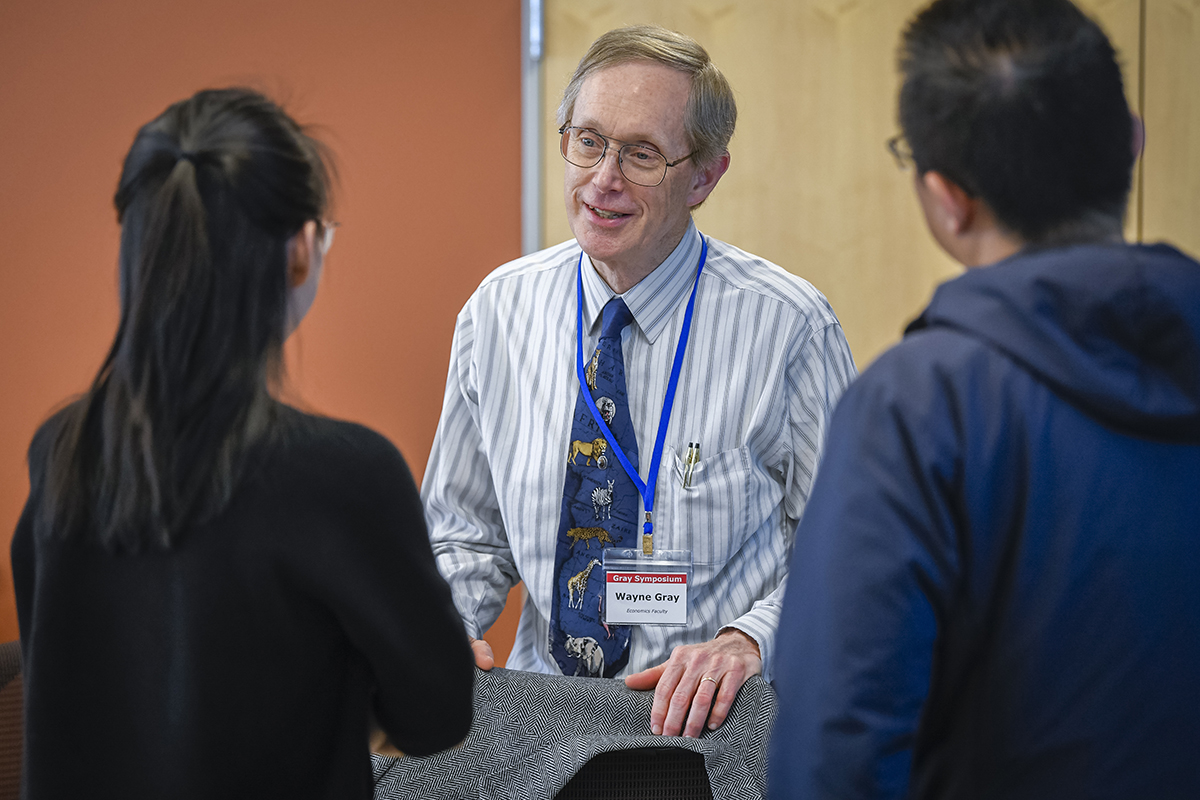

Junfu Zhang, chair of the Economics Department, lauded Gray as a dedicated mentor and accomplished scholar whose dealings with people were “generous and selfless.” Gray was the subject of a recent symposium honoring his career as teacher and scholar that was attended by economics colleagues from across academia as well as former students who have gone on to impressive careers in their own right. At the symposium, some astounding numbers were shared, including the fact that over his 41-year Clark career, it’s estimated Gray helped guide 85 percent of the economics Ph.D. students’ most significant bodies of work. The day’s participants spoke of his enduring impact on the lives of those who learned from him and collaborated with him.

“Wayne’s example reminds us of the best we can be,” Zhang said.

Dean of the College Laurie Ross, who earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees at Clark, noted that she had both Gray and Derr as professors during her sophomore year. Gray, she said, showed patience and passion in the classroom. Derr, particularly in his Medical Ethics class, was “demanding and provocative.” She said that during her time as a faculty member with the Department of Sustainability and Social Justice, O’Brien was a valuable ally in her community engagement work.

Jacqueline Geoghegan, professor of economics, recalled that she urged her daughter to take a class taught by Derr “because he will teach you to think and write.” Doug Little, professor emeritus of history, lauded Derr and Gray for their involvement with faculty governance; and University Librarian Laura Robertson noted the support all three honorees showed for the Goddard Library and its services.