Writing a memoir is no easy thing. When pursued with honesty and courage it can expose old wounds and bring the author to uncomfortable places.

So why do it? Maybe to preserve a legacy, or recapture a forgotten time, or simply to settle scores.

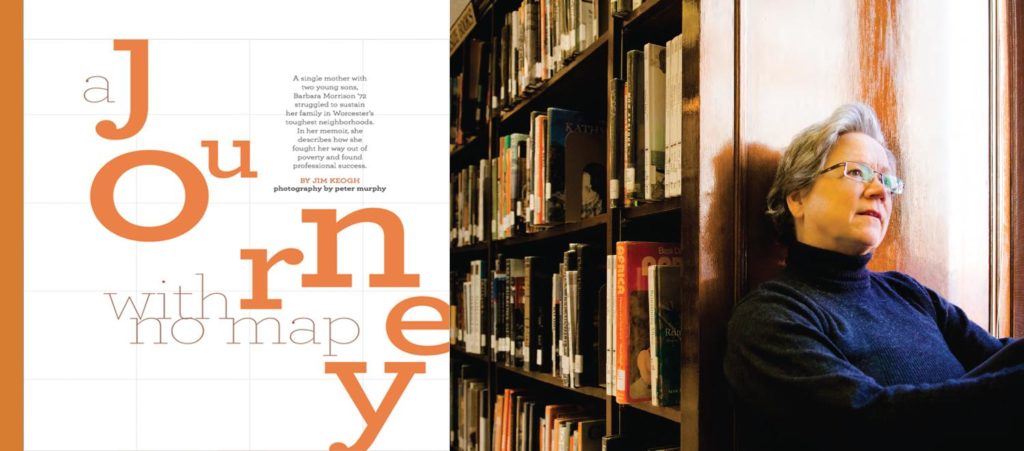

Barbara Morrison had a personal story to tell, but her motivations for writing it were more complicated, and can be traced to the 2000 presidential campaign, when she noticed a hard-edged theme running through much of the national dialogue.

“There was a lot of negativity about poor people and how they were a drag on everyone else, especially the ‘lazy welfare mothers,’” she recalls.

As someone who’d grown up in an upper middle-class household in Baltimore, the daughter of a doctor and housewife, Morrison had heard a similar chorus. Once, as her family drove through a dilapidated Baltimore neighborhood, Barbara’s parents complained about the proliferation of the poor on the city streets. “What we need is a good plague,” her mother said.

But there was something else at play that made Morrison cringe at some of the sentiments being thrown around during that Bush v. Gore campaign season. Despite a successful career as a computer-security engineer, she knew better than most what it was like to literally count nickels and dimes to buy a can of soup, to be uncertain if she and her children would have a roof over their heads and heating oil in the tank. At a particularly vulnerable time early in her life, Morrison, a single mother, had needed public assistance to help her family span the chasm separating mere survival and self-sustainability.

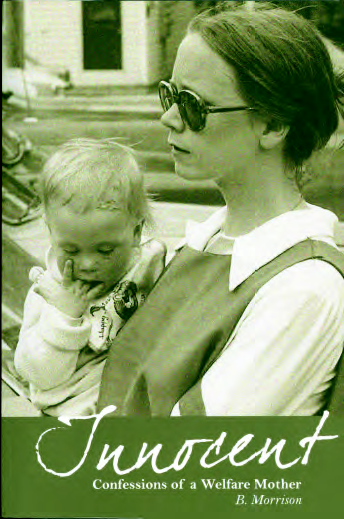

She recounted her journey in the 2011 memoir “Innocent: Confessions of a Welfare Mother,” which gained renewed traction this past November when Forbes.com published a lengthy interview with Morrison in which she refuted many of the prevailing notions about welfare recipients.

“After I got off welfare I never told anybody about it — the people I was friends with, the people I worked with,” she recalls today. “I didn’t want them to know about that part of my life because there was a stigma to it and I was afraid of how my kids and I, but particularly my kids, would be judged.

“During the 2000 election, when there was so much negativity out there, I began thinking what I could do, and I thought, ‘Well, I could tell my story.’”

She initially wanted to write a fictionalized account of her four years on welfare, but a friend pushed her to pen a memoir. To effectively combat the stereotypes, the friend insisted, Morrison had to tell the unvarnished truth about her own experience.

Morrison first took a stab at writing about other people she’d known on welfare, but the information was too scanty, the perspective detached. Members of her writing group maintained that Morrison’s own saga needed to supply the narrative arc.

“I didn’t even make an appearance in the first draft,” she recalls. “I’d be told, ‘This book needs more of you in it. What were you feeling?’ They really dragged it out of me, and it was hard because I’m a private person. The revisions were constant.”’

She used John Steinbeck’s “The Grapes of Wrath” as her guide. In his novel, Steinbeck tackled the great social issues of the day through the prism of the Joad family, forced to escape the Dust Bowl and migrate to California during the Great Depression.

“Steinbeck personalized the story through the Joads, and he made people really feel what they were going through. I wanted to do the same thing, believing that people would relate to one person rather than an anonymous blob of people.”

Morrison came to Clark University in 1970 as a junior, transferring from a Maryland college at the urging of a friend who’d also applied, and enrolled as an English major.

“I enjoyed my classes. Professor Serena Hilsinger was a huge influence. She was the first person to get it through my thick skull that reading critically is different from reading for fun. It was a huge step for me to understand how a book’s structure can enhance the story.”

Morrison fell in love with a local man, “Lewis,” and after she graduated they married. They had a son, Jeremy. Life was hard, but manageable. The job market was flooded with baby boomers, and Morrison worked secretarial positions while harboring a desire to one day go to graduate school and become a teacher. But her relationship with Lewis was disintegrating, and while she was pregnant with their second son, Justin, he left. They later divorced.

Without Lewis’ income or having him around to help care for the boys, Morrison was left making one of the hardest choices she’d ever faced. She writes of that dark time:

“Getting welfare, I reasoned, was like getting unemployment; I had paid taxes for years and would again someday soon. It would be, as it was meant to be, a temporary safety net during a difficult time, as if we’d survived some natural disaster. Indeed, I felt like the victim of a hurricane. My life had been picked up and shaken around and dumped to the ground, leaving me without resources of my own to care for my children.”

And later, after she’d applied for assistance:

“The October wind rattled the windows, threatening our precarious refuge. Hazards of all kinds pressed in around us. In deciding to go on welfare, I had the sense that a door had slammed shut behind me and I was stepping out into the cold, setting off on a journey with no maps, without even knowing what my destination would look like.”

Morrison writes unsparingly about living in poverty in some of Worcester’s tougher neighborhoods during the mid ’70s — of apartments with lead-painted walls and decrepit three-deckers that would mysteriously go up in flames a few streets away. After paying for the rent and heat she would be left with $10 to last the entire month; food stamps helped keep the boys fed, but fresh produce was a luxury (she and a friend started a garden on a city lot). She recounts the humiliating trips to the welfare office downtown, where some of the social workers were helpful, but others often acted as obstacles rather than conduits to the benefits needed to keep her family afloat.

There were days of despair when she found herself fighting the stasis brought about by her circumstances. Morrison writes of circling want ads while knowing that until her boys reached school age she would be unable to work full time because there was no child care. By necessity she’d become adept at repairing her oft broken-down VW Beetle and applied for a government program to earn a certificate in auto mechanics. No, she was told, it’s either beautician school or nothing.

There were good times as well. She found joy in folk dancing and in small pleasures, like watching her boys romp in Elm Park and Crystal Park (now University Park). Her receipt of a grant under the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act to teach creative writing buoyed her spirits and gave her practical experience.

Returning home to Baltimore was not an option. Morrison’s parents had essentially disowned her once she went on public assistance — her mother believed Barbara’s presence would set a poor example for her five siblings. Over the years, Barbara maintained a tenuous connection with her family, but the estrangement persisted.

“It was not an easy life as some people would understand it,” she writes, “certainly nothing like my parents’ lives, wrapped in the cotton batting that a steady and sufficient income provides. It was more like that path up the mountainside, the mud occasionally after a rain but mostly okay. I had to keep going, hold my sons’ hands and ignore the steep plunge of the cliff falling off to the side and no guardrail to catch us, only the flimsy rope connecting us to our community of friends, struggling as we were on the same path.”

Morrison describes in her book what it’s like to be an “invisible” person in a society seemingly intent on convincing itself that you don’t exist. She remembers a friend named Melinda who talked of feeling dehumanized once she accepted public assistance. “When you go on welfare, the system tries to demean you, debase you, discourage you,” Melinda said. “If they could kill you, they might.”

She acknowledges that abuse within the welfare system does exist, yet marvels at the accepted notion that most people on assistance don’t want to work. Morrison and her friends on welfare created a support group — caring for each other’s children, chasing down leads, lending each other clothes for interviews — to try and give one another a leg up on securing a job.

A surprise overture from her mother asking her to come home set Barbara Morrison on a new path. Her siblings had moved out, her father was in poor health, and her mother said they wanted to spend more time with Barbara and the boys. Her parents’ attitude had clearly softened over time, and they were eager to reconnect. After some thoughtful consideration, Morrison accepted the offer.

“One of the difficulties I had writing the book was I didn’t want to blame anybody,” Morrison says. “People at the time acted in what they thought was the right way, even my parents — they were of their time. It all seems very negative now, but the way they thought about welfare, and about me being on welfare, was commonly accepted.

“Some people pointed out to me later that rather than go on welfare I could have forced my parents to take me in. But honestly, I was afraid of them; I was used to being obedient to them. When they said no, I took that as no.”

Back in Baltimore, Morrison earned her education degree and taught eighth grade in the city schools. Despite steady employment, the salary was meager — she earned $8,000 her first year and by 1985 her annual pay was still only $15,000. Her job status was shaky, too. Baltimore’s mayor laid off teachers every summer as a cost-cutting measure, rehiring most of them in the fall. Some of those years, Morrison wasn’t rehired, which meant money was always tight. Living at home supplied some cushion but was not a cure-all — she struggled to pay her parents room and board, and Jeremy and Justin still qualified for free lunches at school.

One day when she was at the bank, the computers broke down and the bank had to close for the day.

“I thought, ‘If I could fix computers, I’d have a job forever,’” she remembers. Morrison enrolled in a technical school and trained for six hours each night while teaching during the day. She was eventually hired full time to develop courses to maintain complex computer equipment, doubling her salary, though she supplemented her income by teaching a basic skills class at the local telephone company. She and the boys moved out of her parents’ home and into a Baltimore row house. Jeremy and Justin thrived at school, and joined a local Episcopal boys’ choir that paid them a small salary to sing. “They’ve worked since they were kids. I never had to give them an allowance,” she laughs.

Morrison later learned that she was hired largely because of her English degree, which allowed her to be the final arbiter over the grammar arguments that broke out when the engineers were writing their reports and composing lesson guides. She eventually moved on to a small family-owned company, where she still works, and shifted into computer-security engineering, a field that was emerging in the early 1990s. Morrison is now a “security architect,” diagnosing companies’ cyber-security problems then designing the strategies to address them.

Her initial assessment about computers has proved prescient. She can fix them, and she’s never been without a job since.

Now in her early sixties, Morrison has known deprivation and prosperity, and that has inspired her to become a quiet crusader for those who are encountering the same kinds of challenges she endured. She makes herself available to speak at high schools and colleges.

“I feel a responsibility to share my story,” she says. “I think it’s good for sociology students and students who are going to become teachers to know something about the people they’re going to encounter, and to be aware that the stereotypes don’t fit.”

She returns to Worcester now and then to revisit old haunts and reunite with friends. And she continues to write, publishing two books of poetry and working on a novel in addition to her memoir.

Her sons have done well. Jeremy is in medical school with the goal of becoming a primary care physician in northern Vermont, where a crying need for family doctors exists. Justin is a web designer.

Morrison says her time on welfare made her a better person. She’d always been guarded, kept to herself. Her experience made her aware of the generosity of others and inspired her to reach out.

“There’s a term now that didn’t exist then: paying it forward. I can never repay the people who helped me, but I can assist others in whatever way I can. You know, even when you don’t have anything, you can help out each other.”

The woman who was once branded as “lazy,” a leech off the taxpayer, today says that the welfare system did what it was meant to do: It gave her family a chance.

“I didn’t feel guilty accepting welfare,” she writes. “I knew that the minimal investment that society made to keep us alive would be paid back thousands of times over as I, and soon my children, became taxpayers. That has happened. I may be the only person who actually enjoys April 15th.”

This story was originally published in CLARK Magazine, spring 2013.