Freight Farms: Bounty in a box

Behind the closed doors of the nondescript trailer in a city parking lot, leafy lettuces and bushy herbs sprout from vertical rows of gutter-like panels. The plants are fed nutrient-rich water while dangling strands of blue and red LED lights bathe them in an otherworldly pink glow.

There is no tractor. No barn. Not even soil. Yet by any definition this is a farm, one that will yield a harvest year-round, regardless of the season. The agricultural operation requires no special skills — just a willingness to embrace technology, and an awareness that a food source existing right outside your door is a pathway toward individual health and collective sustainability.

It’s called a Freight Farm, and it’s agronomy for a new age.

***

Freight Farms is a blooming business with roots at Clark University. Six years ago, co-founders Brad McNamara, M.B.A./ES &P ’13, and Jon Friedman prototyped a hydroponics farm, which they dubbed the Leafy Green Machine, in the parking lot behind Clark’s Recycling Center.

Their goal was to create local, mobile food economies by marrying environmentalism with entrepreneurial vision under the philosophy that sustainability is not a side line, it’s the bottom line.

Today, Freight Farms supplies 40-foot shipping containers retrofitted to grow vegetables and herbs in any location and climate. The company has sold more than 50 rigs across North America, most of them to customers with no farming experience but who see the value of a steady supply of fresh, readily accessible produce for their restaurants, college campuses, hospitals and food-themed start-ups. Google’s campus in Mountain View, Calif., feeds its employees from a Leafy Green Machine.

Freight Farms was bred from its founders’ dissatisfaction with the inefficient and wasteful process of transporting food from grower to consumer, sometimes across the globe. McNamara and Friedman aim to decentralize the food supply chain, bring production closer to the consumer, and dramatically lessen the environmental impact of the farm-to-table journey. “The food system is in need of modernization,” McNamara insists. “We are reducing the problem by reducing the miles.”

They are also using social media to form virtual farming communities. Rather than meeting at the Grange to talk shop, folks log on to Freight Farms’ private Facebook group to learn how others have handled challenges or achieved success from growing crops in a container. McNamara wants his farmers to feel freed up by their farms, not restricted.

“We chose Facebook because everyone’s on Facebook,” he says. “It’s not another thing they have to learn. We want to build tools that empower farmers, not things to make us cool.”

Headquartered on the edge of Boston’s Seaport District, Freight Farms features an on-site container that is a living lab where staffers conduct research on crops and yields, then relay that information to farmers, according to Caroline Katsiroubas, the company’s community manager. Potential farmers participate in a two-day “farm camp” to learn how to operate the system. Green thumbs aren’t required. “Motivation is the number-one skill needed to grow their own food,” Katsiroubas says.

David DuBois, CEO of Franklin Restaurant Group, anticipates the reliability and consistency his Freight Farm will offer his soon-to-open Tasty Burger restaurant in Boston. He plans to place a Leafy Green Machine atop his restaurant. “I can walk upstairs, grab some lettuce and put it on a burger,” he says. “It’s such an efficient tool.”

The desire for reliable year-round farming in places known for tough growing conditions is not lost on McNamara. He says the pressure on growers and distributors is increasing as the public develops a keener interest in locally grown food. Years ago, he notes, consumers expected less variety and poorer quality in the dead of winter. Now they demand the best, no matter the date on the calendar. “We want our salads in February and we want them to be good,” McNamara says. “At the end of the day, we have to grow high-quality food.”

***

Even before he arrived at Clark to pursue dual master’s degrees in business and environmental science, McNamara had been experimenting with growing vegetables. Both he and Friedman had done consulting around rooftop greenhouse development and also were intrigued by hydroponics. McNamara notes that farmers have long figured out how to make do with available resources, finding what works in the face of unpredictable weather, pest infestations and a host of other obstacles. “When you give farmers a piece of equipment, they will get every ounce of value out of that equipment,” he says.

McNamara began to immerse himself in the science of growing, and was surprised to observe that as the New England temperatures cooled his windowsill crops continued to thrive. “My indoor lettuce was growing so much better,” he says. “I thought ‘This is crazy!’ and then became excited about the flexibility of controlled growing. The reason I was so enthralled wasn’t because I loved farming, it was because I liked the fresh lettuce and cucumbers I harvested that day.”

McNamara and Friedman launched a successful Kickstarter campaign to purchase a shipping container. They worked with Jenny Isler, Clark’s director of sustainability, who offered resources, advice and encouragement, and brought in student Eco-reps as volunteers. She also made the key donation of a parking spot on Maywood Street, behind the Recycling Center, to provide a home for that first container. Few knew that the two men entering and exiting the trailer were building a new model for automated agriculture.

The business partners spent six months building, dismantling and rebuilding at least five different versions of a Leafy Green Machine — “We tried every configuration,” recalls McNamara — before perfecting the systems and structures that evolved into Freight Farms.

Among their earliest customers was Clark’s student-run food co-op, The Local Root.

How does a Freight Farm work?

Seeds are planted in peat moss “grow plugs,” and as they bud they are transplanted into recycled plastic mesh that is inserted into the growing towers. The towers are hung from hooks connected to a system that continually recirculates water. A high-efficiency LED lighting system mimics sunlight.

Hydroponics in itself is not new, but Freight Farms is wired for the 21st century. Environmental sensors balance temperature, humidity and carbon dioxide levels. With an internet connection users can monitor their operation anywhere in the world via computer. An iOS app makes it possible to adjust all the farm’s environmental components remotely.

As many as 7,500 plants can be grown in the 320 square feet of space in a Freight Farms trailer. According to the company, a Leafy Green Machine will produce the equivalent yield of an acre of farmland while using 90 percent less water and no pesticides.

All farmers begin growing with a standard protocol, making adjustments as their operation advances. That flexibility is key. Once a farmer has established a system, crops are staggered for a consistent harvest.

Ryan Sweeney’s Minneapolis-based business, Localize LLC, operates two Freight Farms. Sweeney had no agricultural background, but knew there was opportunity in growing 365 days a year. “I built a business around it,” he says. Now selling basil directly to grocers, Sweeney says the longest his basil sits on a shelf is three and a half to four days from harvest. “If you’re getting it from the growers in California, it won’t even get to the shelf in that time.”

***

Freight Farms has come full circle at Clark University. The scruffy two-man startup, which is now a thriving enterprise of 17 employees and counting, has reestablished its presence on campus.

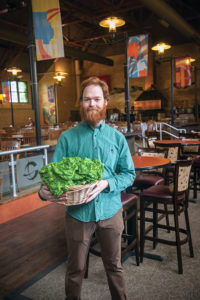

On January 15, the University, in partnership with its Dining Services vendor Sodexo, received delivery of a Leafy Green Machine behind the Lasry Center for Bioscience. The farm provides Clark with fresh lettuce — about the most widely consumed vegetable at the University — whether two feet of snow blankets the ground or the thermometer hits three digits. Eventually, other plants like chives, basil and cilantro may be incorporated into the mix, according to Michael Newmark, general manager of Dining Services. Other options can include leafy greens like kale, cabbage and Swiss chard; and herbs like mint and oregano.

Students are like any other consumers, Newmark says. “They’re demanding more and more locally sourced produce,” he says. “Having a Freight Farm on campus enables us to serve fresh lettuce in our dining operations the same day it’s harvested. Local now means right on campus.”

Clark’s interest in Freight Farms is about more than McNamara’s involvement. In 2013 the University signed onto the Real Food Challenge, committing to use 20 percent “real food” — food that is local/community-based, and ecologically and humanely raised — by 2020. New England’s seasonal variations mean Clark can’t just order the 500 heads of lettuce it requires every week from local growers, Isler says. The new Freight Farm, which Clark has leased for eight months, will likely go through one or two crop rotations to see if it’s suitable for a long-term investment, she notes.

Freight Farm production at Clark serves many purposes, including as a learning lab that demonstrates food can be grown in places otherwise inhospitable to farming. Once the Leafy Green Machine was made operational, graduate students Kamalan Chandran, M.S.I.T. ’16, and Rebecca Miller ’15, ES&P ’16, tended the plants daily and harvested the lettuce weekly. Coincidentally, Miller worked with McNamara and Friedman on the early Freight Farms prototype when she was an undergraduate.

“The best part of this is to bring it home,” Isler says. “The idea that this is an urban alternative for fresh and healthy food is huge.”

***

Jon Olinto, co-owner of B.GOOD restaurants, formed a partnership with the owner of a Leafy Green Machine to have kale at his Boston locations during the colder months. In the summer, the restaurant will turn to traditional farmers for kale, but he hopes to use the hydroponics space for more delicate and less common greens like mache.

Olinto says having access to fresh kale in winter is wonderful, and he coaches his employees to understand the importance of the sourcing. “It’s pretty simple,” he says. “If you want someone to care about something, you show it to them, and then they can explain it to our customers.”

McNamara expects to see Freight Farms growers begin disrupting food distribution patterns. As he sees it, local distributors can rely less on what the larger food brokers offer, and now have the flexibility to develop specific relationships with farmers based on needs and demands.

“It would flip distribution on its head, where the local becomes the go-to,” he says. “There’s no denying the impact if we can stay in the community, keep food local and create food independence. We want the focus to be on the farmers and the people they’re feeding.”