The long goodbye of a good man

Editor’s Note: “With Dad,” the award-winning documentary directed by Screen Studies Professor Soren Sorensen based on Stephen DiRado’s story and book, will premiere on GBH (Boston’s PBS station) on Tuesday, Sept. 21, at 7:30 p.m. The film is available to stream on the GBH website.

Stephen noticed the small changes first.

His father, Gene, seemed to be pulling back at family gatherings, hovering at the fringes of conversations or disengaging entirely to go watch television by himself. He got lost driving to familiar destinations. At work, he was disorganized and confused. People noticed.

That Gene’s cognitive decline was the result of Alzheimer’s disease came as no surprise when the diagnosis finally was made in 1998, after he’d exhibited uncharacteristically eccentric behavior for some time. The doctors only confirmed to Gene’s wife and children what they’d suspected: Gene was retreating into his own mind, a journey on which they could not accompany him and from which there would be no return.

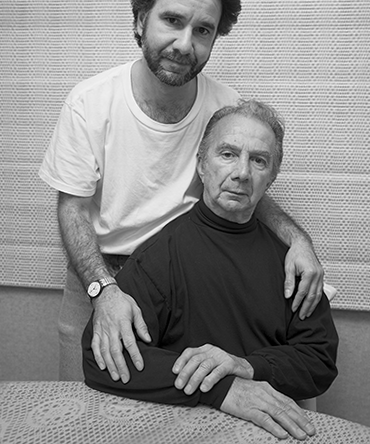

Stephen DiRado, a longtime professor of photography at Clark known for his naturalistic images of everyday life, had for years photographed his father for posterity’s sake, capturing Gene at work and in repose, with family and alone. The task now took on new urgency. He threw himself into documenting this unfolding odyssey through the camera lens, first while Gene still lived at home, then for five years after his father was moved into a nursing home — right up until the moment of Gene’s death.

Many of the photos have been collected in the recent book “With Dad,” which chronicles Gene’s decline. The story these images tell has also been adapted into an award-winning documentary, directed by Clark Screen Studies professor Soren Sorensen, that has been making the film festival circuit.

Both the book and the film distill the DiRado family’s private pain but also supply glimpses of peace and acceptance, of vulnerability and grace — of life, death, and art.

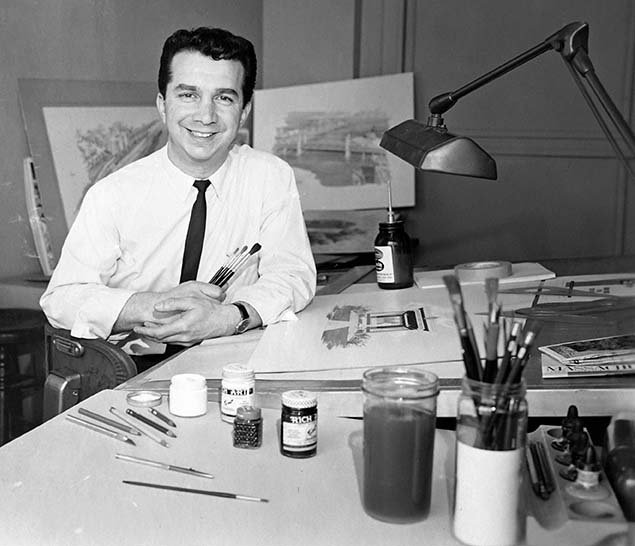

Gene DiRado had always paid attention to appearances, especially his own. His goatee was neatly trimmed; his ties were the best silk; he smoked fine cigars. That dash of style set him apart from the other members of his extended blue-collar family, yet also endeared him to them. Gene managed a team of graphic artists at the Massachusetts Department of Public Works, where he crafted maps that helped orient both locals and visitors alike and fashioned illustrations trumpeting the virtues of state construction projects. Off hours, he played drums in a jazz band. “My dad,” Stephen says, “was pretty damn cool.”

Gene taught Stephen to paint and draw, and sometimes brought him to his job in Boston. When Gene was busy, Stephen would wander the city, visiting museums and studying people just as he’d always studied his own family. (“They were different times,” he acknowledges. “I never felt unsafe.”) His dad would take him to lectures at the Boston colleges and bring him to an area observatory to stargaze until dawn. A shy kid who sometimes felt adrift amid his boisterous Italian-American clan, Stephen was exposed to the wider world with his father as his wise and gentle guide.

The die was cast when Stephen was introduced to his dad’s stash of old cameras. Soon, Stephen was shooting everywhere, making art, scaffolding a career, finding his voice. By the age of 14, he was photographing for his hometown newspaper in Marlborough, Massachusetts, and sometimes would bike the 20 miles to Worcester for assignments in the city. When he graduated from high school, he was offered a full-time photography position at the paper. Gene was not amused.

“He said, ‘I will break your legs if you take that job,’” Stephen recalls with a laugh. “He told me I needed to go to college and get a degree because nobody can take that away from you.”

Since Gene DiRado was reserved by nature, the early clues that something was amiss were easily attributed to “Gene being Gene.” But his behaviors worsened. He seemed bored, depressed, incurious — his reticence to engage devolved into full-on withdrawal. One day, when Stephen asked him to count to 10, Gene abandoned the task after struggling to reach the number 4.

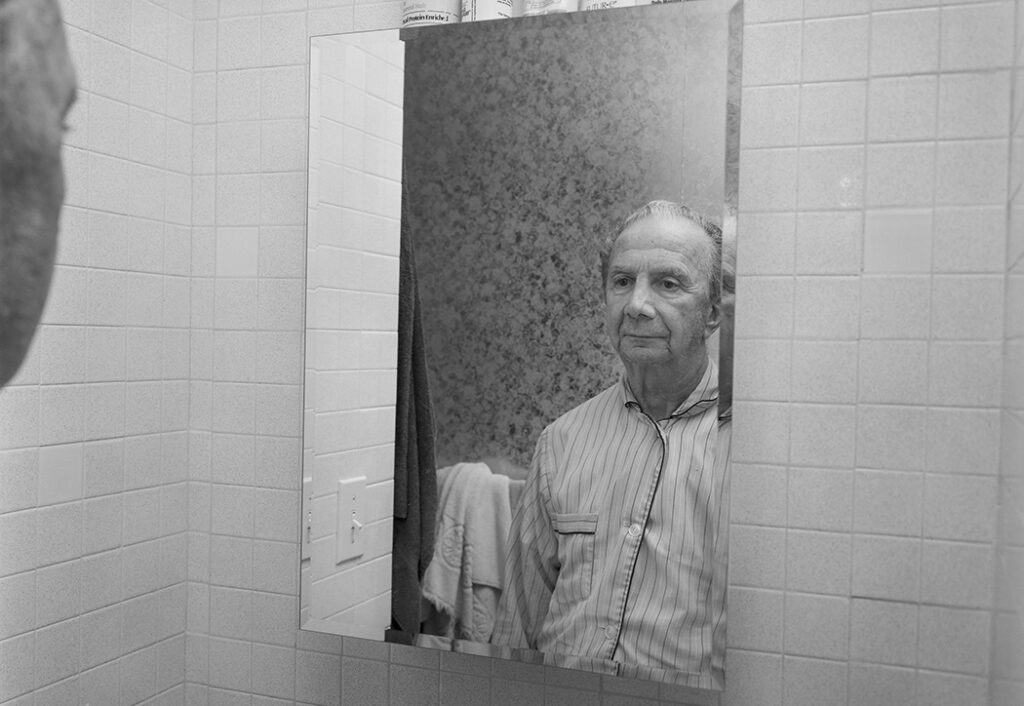

Family members began caring for Gene in shifts. During his turns, Stephen noticed his father going into the bathroom with greater frequency and for longer durations, and reemerging without having run the faucet or flushed the toilet. He discovered his father had been staring at his reflection in the bathroom mirror without recognizing the man looking back at him. Intrigued, “Stephen asked Gene what he thought of the stranger in the glass. ‘He is a good man,’ Gene replied.”

The answer was both heartwarming and heartbreaking. Gene had passed a threshold, his inward march growing more pronounced. The DiRados — Stephen, his mother, Rose, and his siblings, Gina and Chris — determined they could not care for Gene at home any longer and made the difficult decision to admit him to Marlborough Hills Rehabilitation & Health Care Center. Here, Stephen assumed the responsibility of chronicling the last years of his father’s life.

Twice a week for five years, with the permission of the administration, Stephen lugged his 40-pound Roloflex box camera and tripod into Marlborough Hills to capture Gene on film.

“To my father in those first few years, I was his son, Steve, with a camera. As the disease advanced, it was the camera that just happened to have Steve by its side. By the last few years, when I walked into the room, everything vanished. The camera didn’t exist. I didn’t exist. I watched him slowly erase the world around him and I disappeared, and the camera disappeared.”

Over time, Stephen became an unofficial artist-in-residence at Marlborough Hills. Staff members would wander over to him as he positioned his camera and ask, “Steve, what do you see today?” Once, as he rode the elevator with one of Gene’s nurses, she pointed out that his father had long exceeded the life expectancy of an Alzheimer’s patient. “You know why he’s still here, don’t you?” she asked. “It’s so his son can make great art.”

“Photographing my father was a way of controlling something,” Stephen recalls. “I would take a photo, go home and print it, and look at it. This was a frozen moment in time — something was going on right before my eyes. I couldn’t deny it, couldn’t lie to myself about it.”

The photos in the latter stages of Gene’s life depict the terrible toll of the disease. The man is visibly shrunken in his wheelchair, nearly unable to keep his head upright. In his last month, he clutched a teddy bear during his waking hours. “I knew he would not be here much longer,” Stephen says.

Gene died on December 11, 2009, surrounded by his children. Rose had been in Florida and was in hurried transit to Massachusetts to try and reach the nursing home in time. “In the final photo, I intentionally cast a shadow on the wall behind my sister to represent my mother’s presence,” Stephen remembers. “I told my father, ‘Dad, this body has failed you miserably. I love you dearly, but you need to move on to bigger and better things.’ I asked him if he understood me to please move his right foot back and forth three times, and he did.”

Gene died on December 11, 2009, surrounded by his children. Rose had been in Florida and was in hurried transit to Massachusetts to try and reach the nursing home in time. “In the final photo, I intentionally cast a shadow on the wall behind my sister to represent my mother’s presence,” Stephen remembers. “I told my father, ‘Dad, this body has failed you miserably. I love you dearly, but you need to move on to bigger and better things.’ I asked him if he understood me to please move his right foot back and forth three times, and he did.”

In his preface to “With Dad,” Stephen DiRado wrestles with the question of why he photographed his father in the grip of Alzheimer’s.

“I did it to hold on to my father as long as possible,” he writes. “I did it to record a disease that, I believe, in time will no longer be terminal. I did it as a visual, visceral record for future generations to see what devotion, heartbreak, and suffering looked like for victims of Alzheimer’s and for their families.

“I did it for my father.”