‘I need to share this story’

When she was 14, Carolyn Michael-Banks stood at the Door of No Return.

Peering out at the Atlantic Ocean, she knew she was standing in the footsteps of thousands — perhaps millions — of West Africans who had passed through this infamous door at Elmina Castle, on the coast of Ghana, and onto slave ships, never to see their homeland again. It was a defining moment.

I need to share this story, she thought.

Back home, the Bronx native told her classmates about her summer vacation in Africa. “What were the jungles like?” they asked. She quickly realized that many of them thought “Africa” was one unruly, tribal, tropical place, not the world’s second-largest continent with more than 50 nations and a range of industries.

“There was so much misinformation that I wanted to correct it,” she says.

She’s been correcting it ever since.

•••••

Michael-Banks’ company, A Tour of Possibilities (ATOP), offers sightseeing tours of Memphis, Tennessee, with a focus on the history of and contributions made by African Americans in the largest city on the Mississippi River — starting with how the city got its name.

Memphis was once the capital of ancient Egypt, an important center of trade and commerce situated on the Nile from about 2925 B.C. to the mid-seventh century.

“The founding fathers of our Memphis were aware of the greatness of Memphis in Africa, and anticipated the greatness to come in our city,” Michael-Banks says. “Add the fact that ancient Memphis sat on the Nile and ours sits here on the Mighty Mississippi.”

Michael-Banks’ customers take her tour while sitting in a 10- passenger van — at least, they did until COVID-19 forced her to rethink her model. In the pandemic, visitors follow the ATOP van in their own vehicles and tune into the tour via a Bluetooth link.

Her visitors see Memphis’s famous sights, including the Pyramid, a former arena — built in 1991 in homage to the Great Pyramid of Giza — that now is home to restaurants, a hotel, stores, and more. But they also see sights and hear stories that are central to the African American experience.

She highlights Auction Square, where enslaved people were bought and sold, and the Slave Haven Underground Railway Museum. Cossitt Library, where students from LeMoyne Owner College, Memphis’ only historically Black college, held sit-ins because they were not permitted to use the facility for their research. And Shelby County Jail, where Lee Walker was held in 1893 after being accused of assaulting two white women. A mob broke into the jail, dragged him out, and lynched him — burning and mutilating his body for souvenirs. Michael-Banks uses Walker’s story to note that the U.S. still does not have a federal anti-lynching law on the books.

“When you take my tour, it’s a roller coaster. One minute we’re laughing, talking about people who escaped from prison, and the next I’m talking about a lynching that took place next door. You don’t know what to expect — which is the way history is,” Michael-Banks says. And she doesn’t shy away from connecting the past to the present, especially if it offers a way to educate.

One of the sights on the tour is Fourth Bluff Park, formerly called Confederate Park, which until 2017 had at its center a statue of Confederate president Jefferson Davis. Last year, when calls to remove monuments to Confederate generals escalated after the killing of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis, some people on her tour insisted the Civil War had nothing to do with slavery. “That’s what they were taught, so that’s what they know,” she says. “In their eyes, the protests didn’t make sense.”

Michael-Banks seizes moments like this to correct the misinformation, as she did when she returned from Ghana as a teen. “That’s my mission now,” she continues. “I’m doing it at a very small level, which is fine — because small is where you’ve got to start.”

•••••

Carolyn Michael-Banks did not come to Clark intending to forge a career in tourism. She was a psychology major with a sociology minor.

She learned about the University from her brother, who was thinking of attending before he accepted a football scholarship to Columbia. One attraction was Clark’s small size. “I needed to go somewhere I wouldn’t be a number,” she says. “I wasn’t excited about how the winters would be, though.”

One of those Clark winters included the Blizzard of ’78, when she was trapped in Hughes Hall for the duration. “That altered my life,” she laughs. Illness spread through the dorm, and one student even had to be airlifted out. A friend who lived off campus trudged through the snow and brought a hot plate and hot dogs. “We lived off those hot dogs for four days,” she recalls. “We sliced them thin and put some kind of seasoning on them. It was like filet mignon.” She resolved then that she would one day live in a warm climate.

Michael-Banks, who grew up in a neighborhood that she describes as a “24/7 United Nations,” was in a small minority of Black students on campus, and usually the only Black person in her classes. This left her in the default position of explaining the African American experience to her classmates and professors. When the groundbreaking television miniseries “Roots” aired, a professor asked what students thought of its depiction of slavery. Michael-Banks recalls a white classmate raising her hand. “She said, ‘You know, I truly believe this was made for TV. There’s absolutely no way that what I saw could have happened in any way, shape, or form.’ And then I felt the eyes.”

Her classmates turned to Michael-Banks for a response. “I said that I could understand her feeling that way,” she says, “because she probably hadn’t ever seen it, heard it, smelled it, tasted it. The reality, probably, is that what we saw in ‘Roots’ hardly scratched the surface, and that there was still so much that we’ll never know.”

Michael-Banks says she didn’t mind taking on the role of teacher— in fact, she welcomed it, as she always has when encountering insensitivity or ignorance. “I really wanted people to ask me what they wanted to know,” she says. “One of the reasons why we went away to college was to have certain experiences, and I had so many incredible experiences growing up that I was comfortable with you no matter who you were — but I knew that was not true for everyone.”

•••••

Michael-Banks worked as a social worker in Massachusetts after graduating from Clark. “At the time, I just knew that was my path — until I took the path,” she says.

For two and a half years, she worked to protect abused children, hoping that her interventions would have a positive impact on their troubled lives. She saw her fellow social workers self-medicate and take out malpractice insurance to protect themselves from lawsuits filed by families who didn’t appreciate their efforts, and she had enough. “I realized that this was not why I was on the planet — but it was hard, because I was going to save the world. That’s one thing about Clark. We all have this heart to help the world.”

She left to live with her sister in Washington, D.C., and got a job as a tour guide with a company she had worked for during one of her summer vacations. But she balked at the lack of African American history being presented and began inserting little-known facts into the scripts. For instance, she told tourists about Benjamin Banneker, an African American mathematician and astronomer who was hired to survey the land staked out for the new U.S. capital city. When architect Pierre Charles L’Enfant failed to stay within his budget and design mandates and ultimately was let go, he took his plans with him. Banneker quickly stepped in to reproduce the design from memory.

Michael-Banks’ script additions weren’t always welcome. Some customers complained that her storytelling made them uncomfortable.

“Former First Lady Michelle Obama used to speak about how it felt for her to be First Lady in a house that was built by people who were enslaved. I was revealing that truth about the White House long before the Obamas moved in, and many customers just did not want to hear it,” she says.

Michael-Banks convinced the company’s CEO she could create and market a popular African American history tour of D.C. She did just that, but then had to take a medical leave. When she returned, all her posters and marketing materials had been removed.

She was relocated to Savannah, Georgia, to open the company’s tour operation there. After researching and writing the tour script, which included African American history, she was moved again, to Philadelphia, where she did the same thing. That move changed her life, because she met her future husband, a Philadelphia native who lived in Memphis.

Eventually, Michael-Banks was laid off from the tour company, so she headed south to the city where African American journalist Ida B. Wells refused to leave her first-class train carriage in 1884, the blues blossomed on Beale Street, and slavery had once been a thriving business. She saw an opportunity in Memphis to tell the stories behind the stories.

•••••

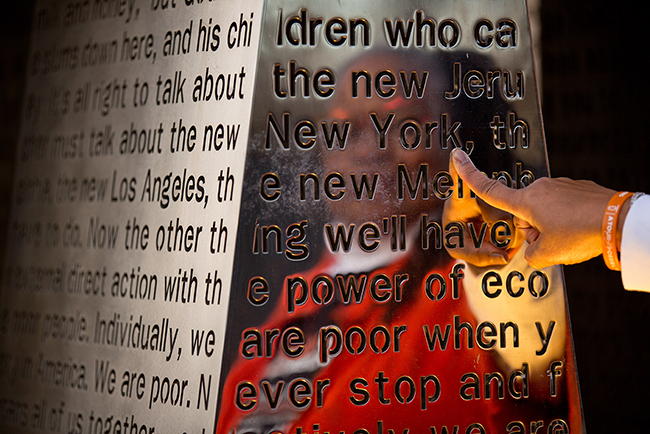

A notably poignant part of A Tour of Possibilities in Memphis is the National Civil Rights Museum on the site of the former Lorraine Motel, where Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated.

The museum’s creation was spearheaded by D’Army Bailey ’65, who was brought to campus in 1963 by Clark students after being expelled from Southern University for leading protests. Bailey went on to become a legendary Memphis judge and civil rights activist.

Michael-Banks met Bailey just once, about a year before his death in 2015. She saw him at an event, marched up to him, and identified herself as a fellow Clarkie. Their connection was immediate. “We were supposed to get together for a little Clark reunion,” she says, but they couldn’t make it happen.

She has connected with D’Army’s son, Justin Bailey ’00, a Memphis native. “A lot of what compelled my dad to establish the museum was his desire to correct the record,” Bailey says. “Carolyn’s tour fills in a lot of the gaps.” He took the tour himself a few years ago, and was surprised by what he didn’t know about his own city. Michael-Banks pointed out Black-owned businesses along the way, Bailey says, a gesture he knows would have pleased his father.

On her tours, Michael-Banks introduces herself as “Queen” — the conductor for the journey.

“I do that intentionally,” she says. “Something shifts in me to connect me to the motherland.”

When that shift takes place, Carolyn Michael-Banks asks her visitors to accompany her to where she thinks they need to be. To imagine a time when Memphis was not the Memphis of today; when the Door of No Return slammed shut on too many who endured under the cruelest circumstances; when new histories were being written by Black Americans across the nation.

And then she begins to share their stories.