Two magazine covers, appearing more than five years apart, make Jeffrey Jensen Arnett alternately cringe and smile.

The first, from the Jan. 24, 2005, TIME magazine, shows a man in his twenties, dressed in business-casual attire, sitting in a sandbox and looking wistfully into the distance. The accompanying spring 2014 headline reads: “Meet the Twixters, young adults who live off their parents, bounce from job to job and hop from mate to mate. They’re not lazy…THEY JUST WON’T GROW UP.”

That’s the cringe-worthy one.

Then there’s the Aug. 18, 2010, cover of The New York Times Sunday Magazine, which featured photographs of young adults in a number of poses and situations—serious, playful, contemplative—with the headline, “What Is It About 20-Somethings?” When the Sunday Magazine story, researched and written by Robin Marantz Henig, was published online, “I began reading it with a lot of anxiety,” recalls Arnett, a Clark University psychology research professor. “How many chances do you have for national media? This might be the last opportunity to get my work into the public eye in the right way—in a credible way. As I read, my smile got bigger and bigger, and by the end I was ecstatic and grateful. She nailed it; she really got it right.”

“It” is Arnett’s research into the phenomenon he calls “emerging adulthood,” which covers roughly the ages of 18 to 29 and is defined by five characteristics: identity exploration, personal instability, self-focus, a feeling of “in-between,” and, perhaps surprisingly given the sensation of being unmoored that can occur within that age span, what Arnett describes as “a sense of the possibilities,” essentially an overriding optimism that belies their uncertainty.

Henig’s piece was shaped around Arnett’s contention that emerging adulthood is in fact a new life stage, as distinct and tangible as adolescence, which was legitimized as a life stage at the turn of the last century thanks to the research and advocacy of Clark’s first president and renowned psychologist G. Stanley Hall. With Arnett’s research figuring prominently, Henig helped open up a debate about why young people are apparently taking longer than past generations to hit the traditional markers for adulthood, like establishing a career, finding a life partner, having children, and breaking financial ties with their parents.

Arnett sees this time lag as a natural extension of an evolving culture that places less emphasis on marrying early and starting a family, and of an economy where the traditional manufacturing jobs that buoyed the fortunes of many young people are disappearing. New employment paradigms requiring more education and training than ever before have left young people taking until at least their late twenties to settle into long-term jobs.

Critics dismiss these delays as merely a “failure to launch,” an unwillingness, or fear, to move on with life and a desire to remain bubble-wrapped in a sort of perpetual adolescence. The perception prevailed in the 2005 TIME story, which Arnett, who was quoted in the piece, derides as “hostile, derogatory and appalling.”

In the teeth of perpetual skepticism, he now finds himself championing a group that doesn’t have many natural allies.

Arnett picked up the emerging adulthood thread in the early 1990s while teaching at the University of Missouri.

“It was such a big idea, and it was just lying there. I wondered how it was that everybody was walking by it and not picking it up?” he recalls. “It never made sense to think of young adulthood as age 18 to 40 or 45, as we’d always done in psychology. By the early ’90s, when I started doing my research, it made even less sense than ever because people were marrying later, pursuing education longer, and having fewer children.”

In 2000 Arnett published his first paper explicitly using the term “emerging adulthood” and says the concept was immediately embraced by scholars. The paper has been cited more than 4,000 times, he notes.

In 2004 Arnett published “Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens through the Twenties,” where he fleshed out his findings and affirmed his contention that a new life stage was hiding in plain sight (the book is being reissued this spring with new chapters, including one about social media use).

“I expected more opposition than I got initially; every new idea has opponents who are thinking in old ways,” he says. The main objection was that his research pool wasn’t heterogeneous enough and didn’t take into account social and economic disparities. Arnett counters that he was careful not just to study college students, and interviewed a rich diversity of respondents. He conducted several hundred interviews for the book.

Arnett’s overarching findings are that emerging adults defy the stereotypes so often promulgated in the popular media: the overeducated barista serving lattes; the basement slacker leeching off the good graces of mom and dad; the commitment-phobe consigned to eternal singlehood.

The truth, he says, is far more nuanced and, since it fails to fit into a convenient narrative, often goes underreported. Emerging adults are, indeed, searching for their niches—professionally, romantically, even spiritually—but they are far less inclined to compromise and won’t be rushed. They are compelled to follow through on certain experiences, like travel or volunteer work, before settling down.

“I think the claim that they’re selfish isn’t true,” Arnett says. “They are focused on self-development, but I’ve found that they are remarkably generous-hearted in terms of wanting to do some good in the world. It’s not a matter of never wanting to grow up; it’s a matter of doing some things you’re never going to have the chance to do again.”

Despite being buffeted by a creaky economy that in many cases is forcing young adults to delay or change career plans, they remain optimistic about the future. Arnett says he was struck by this, noting that the positive outlook cuts across social and ethnic groups.

Despite being buffeted by a creaky economy that in many cases is forcing young adults to delay or change career plans, they remain optimistic about the future. Arnett says he was struck by this, noting that the positive outlook cuts across social and ethnic groups.

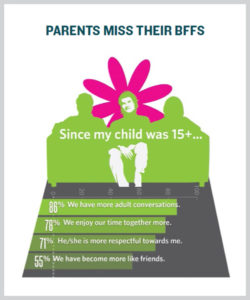

Last year, Arnett published “When Will My Grown-Up Kid Grow Up?” which addressed the hopes and concerns of parents of emerging adults (the paperback is being released this spring with the new title “Getting to 30”). His research shows that, contrary to popular notions, most parents are not hostile to the idea of their adult children moving home for a time as they find their way, and in fact, they are remarkably welcoming. The idea that parents are fed up with their grown children’s failure to break away, he says, was branded in the hit HBO series “Girls” in which the parents of Hannah, the show’s lead character, cut her off financially, forcing her to fend for herself as a writer in New York City.

“Both parents and emerging adults are very similar in how they view adulthood,” Arnett says. “Accepting responsibility for yourself is viewed as the most important component, and that includes reaching financial independence. But when an emerging adult moves home, it’s almost always out of necessity. I’ve found that emerging adults would rather live independently, even if that means living at a lower standard of living, rather than come home.”

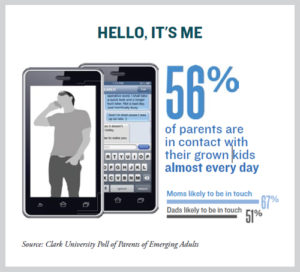

Arnett’s findings are backed by two Clark University-commissioned polls: 2012’s “Clark Poll of Emerging Adults,” and last year’s “Clark Poll of Parents of Emerging Adults.” The polls, which have earned national coverage in outlets like USA Today and The Wall Street Journal, identify sources of conflict and agreement between grown children and their parents, and they have produced a compelling result: 77 percent of 18-to 29-year-olds polled believe they will have better lives than their parents, and 69 percent of parents agree. And despite the unstable economy and the difficult job market, nearly 90 percent of emerging adults polled said they are confident they will eventually get what they want out of life.

“You would think the parents would be pessimistic even if the kids were not, but both groups believe that the kids are going to have a good life,” Arnett says. “I think the reason is that when you’re young, nobody knows how your story is going to turn out, and nobody, neither the parents nor the kids, believes that it’s going to turn out badly. You can understand that, while the story is still being written, these young adults would be aiming high and having high hopes, and their parents who love them deeply share high hopes for them.”

The New York Times Sunday Magazine cover story spurred widespread interest in Jeffrey Arnett’s research on emerging adults. His inbox was immediately flooded with emails, many from people thanking him for his insights, others asking him to “fix” their grown children, and some declaring that these young adults are coddled whiners. He is now regarded as an international expert on a group often painted with a wider brush as “millennials,” and he is frequently sought out by major media for his views.

The New York Times Sunday Magazine cover story spurred widespread interest in Jeffrey Arnett’s research on emerging adults. His inbox was immediately flooded with emails, many from people thanking him for his insights, others asking him to “fix” their grown children, and some declaring that these young adults are coddled whiners. He is now regarded as an international expert on a group often painted with a wider brush as “millennials,” and he is frequently sought out by major media for his views.

From the Associated Press to Le Monde in France, Arnett’s expert comments have accompanied countless news stories about the concerns and aspirations of emerging adults. His research has been featured prominently in such media outlets as the “Today” show, Chicago Tribune, Toronto Star, Daily Mail (U.K.), The Huffington Post, and Congressional Quarterly.

Some of the coverage has been in-depth and even scientific; some has taken a more sensationalistic approach, exploiting generational complaints and tropes about emerging adults as narcissistic freeloaders. Arnett always endeavors to correct the harsher positions. In one live interview on a morning TV news broadcast in Chicago, he deflected a barrage of stereotypical statements and questions from no fewer than four news people at once, including the network’s weather man.

“People are generally favorable,” Arnett says. “I’ve often had people come up to me after a speaking engagement and say, ‘Thank you for explaining where I’m at in life. I feel a lot more normal now.’ Time and again, parents have said, ‘Thank you for helping me understand my kids; they make a lot more sense to me now.'”

The attention also has its downside. Arnett recalls a man from Oregon who called him at midnight seeking help with his personal problems. Another woman took umbrage when he wouldn’t counsel her.

The attention also has its downside. Arnett recalls a man from Oregon who called him at midnight seeking help with his personal problems. Another woman took umbrage when he wouldn’t counsel her.

“Just because I was quoted in a newspaper doesn’t mean I’m Oprah,” he says. “My response [to the Oregon man] was that I don’t even know you, I can’t fix you. I suggested he find a therapist in his area who can help him.”

Arnett is unafraid to battle what he refers to as “the last acceptable prejudice in America.” As he sees it, the culture has become more intolerant over the last half century of biases based on ethnicity, sexual orientation or gender, yet there are few qualms about branding young adults as perpetual slackers. When a Boston Globe column in November accused emerging adults of being “a generation of idle trophy kids” he fired off a letter to the editor defending them, something he’s done time and again in print and in person throughout his career.

“For some reason, it’s still acceptable to dump on kids,” he laments. “There’s a real contempt for them as a group, and I’ve puzzled over why.” Arnett says young adults may need to organize to battle misperceptions, create their own version of a civil rights or a gay rights movement, so to speak. “It’s unfortunate, especially at a time of life when most of them are already struggling. I don’t think it helps anybody to be scorned and ridiculed.”

Arnett is now turning his attention to what he terms “established adulthood,” the ages from 25 to 39 when life courses have been channeled in specific directions. This spring, Clark has commissioned a third poll to determine this group’s attitudes toward many of the same issues examined in the first two surveys. Taken in their entirety, the three polls provide a research continuum, comparing and contrasting the respondents’ views on comparable topics from ages 18 through about 65.

Arnett is now turning his attention to what he terms “established adulthood,” the ages from 25 to 39 when life courses have been channeled in specific directions. This spring, Clark has commissioned a third poll to determine this group’s attitudes toward many of the same issues examined in the first two surveys. Taken in their entirety, the three polls provide a research continuum, comparing and contrasting the respondents’ views on comparable topics from ages 18 through about 65.

“This period of established adulthood is just as interesting and unexplored as emerging adulthood once was,” Arnett says. “The thirties are an intense decade of life. Often you commit to a partner, have a child, and begin making your way along a career path all at once, so there’s a collision of goals and responsibilities. These are things that are happening for almost everybody, but the research has been on isolated areas like marriage satisfaction, career development and transition to parenthood. Nobody’s brought it together and looked at what the whole human being is like in this decade.

“I’m having the same feeling I had twenty years ago,” he adds. “It should be interesting to see if this will be as enlightening to people as emerging adulthood has been.”

This story was originally published in CLARK Magazine, spring 2014.