#ClarkTogether

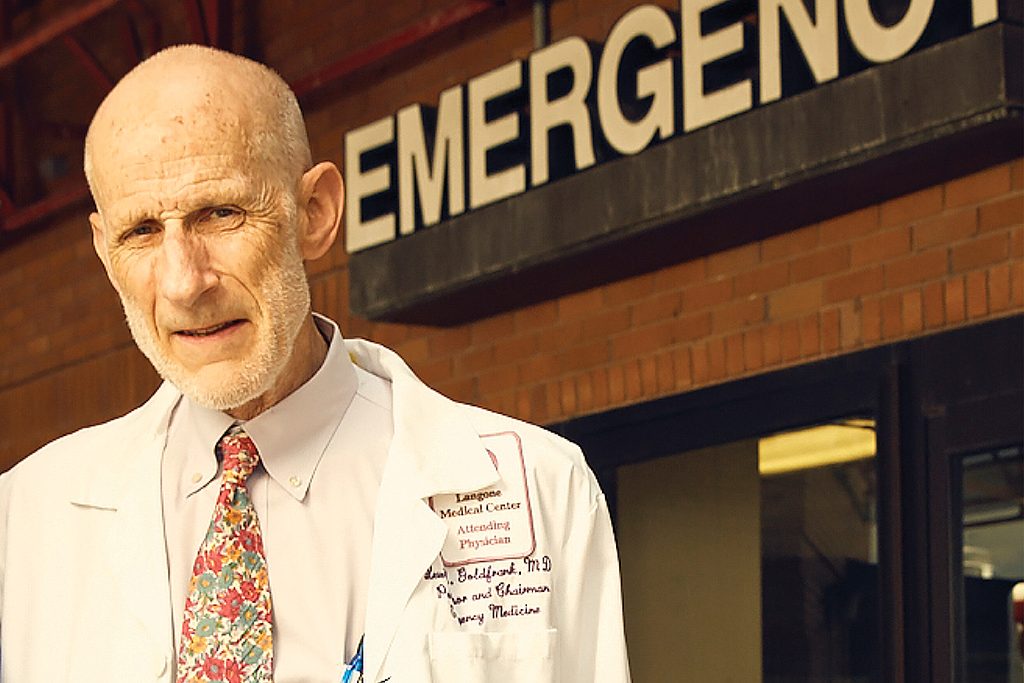

From Camus to COVID-19: Dr. Lewis Goldfrank ’63 battles the deadly virus

As a Clark University undergraduate, Dr. Lewis Goldfrank ’63 read Albert Camus’ “The Plague,” about a deadly epidemic raging across the Algerian city of Oran. The novel detailed not just the disease’s physical toll, but the social and emotional chaos unleashed by a monster that terrorizes the citizens of Oran at a microscopic level.

Decades later, Goldfrank is battling a real-life contagion seemingly snatched from Camus’ fiction. The former longtime director of emergency services at Bellevue Hospital Center in New York City, and still a practicing emergency physician there, Goldfrank and a small army of doctors, nurses, and technicians are treating the victims of COVID-19 who have streamed into their hospital over the course of several weeks. The work is all-consuming for the Bellevue team as it is for the nation’s medical community; New York, however, lies at the contagion’s epicenter. As of this writing, New York state has suffered nearly 2,000 coronavirus-related deaths, with the city accounting for most of the state’s more than 83,000 confirmed cases.

“Every bed is filled by someone who has COVID-19,” Goldfrank says of the Bellevue Emergency Department. “I talked to one of my residents, who put a tube in the tracheas of 10 people during an eight-hour period. Typically, you would do 10 intubations over the course of several months.”

At 78, Goldfrank has deep experience practicing emergency medicine during historic events. He arrived at Bellevue in 1979 during the first flush of the AIDS pandemic — every bed in his Emergency Department soon was occupied by someone suffering from the then-mysterious and lethal illness. He was on the front lines during the SARS and H1N1 outbreaks and the anthrax scare following the 9/11 attack. Each occurrence provided Goldfrank and his peers an opportunity to improve and refine the delivery of care during a crisis.

“These kinds of events bring a community together, but they also force us to do difficult things that must be done with decency and concern,” he asserts. “We must have the knowledge and courage to defend the health of our society on a continual basis.”

“The only way you can ever be prepared for an event of this nature is to be prepared all the time.”

The overwhelming number of COVID-19 cases means crisis protocols are being employed, which alters the typical approach for non-virus-related cases, Goldfrank notes. For instance, someone who arrives in the Emergency Department complaining of abdominal pain will be examined and receive the necessary diagnostic tests, then will be sent home if the tests are negative and there is no apparent need for further treatment. In normal times, he says, the patient would be kept under observation for a number of hours. But today, an extended stay in the Emergency Department places them at greater risk for contracting coronavirus.

“The probability that their abdominal pain is appendicitis is significantly lower than the probability of getting the virus, so it’s best for them to go home,” Goldfrank says. “People who would normally come to the Emergency Department with aches and pains are now waiting it out because they’re trying to avoid the hospital.”

Those who arrive at the Bellevue Emergency Department with mild symptoms of COVID-19 also are sent home. “We only test the very sick,” he says. “You might have COVID-19, but there are no treatments and no space to stay here. You’ll come back if you get sicker.”

Goldfrank stopped doing clinical work in the Emergency Department last week, because his age makes him more susceptible to the virus’ most dangerous effects. He has immersed himself in the role of educator, speaking daily with the Bellevue residents and faculty “to work on resilience, understanding, and the humanism behind the kinds of decisions that need to be made.” Those lessons are relayed through daily videoconferences and in specialized instructional sessions covering topics such as the allocation of ventilators, biomedical ethics, and crisis standards of care.

One particularly sensitive subject covered in Goldfrank’s sessions is how to communicate with the family members of a patient dying from COVID-19-related complications. To prevent the virus’s spread, protocols prohibit families from being in proximity to a terminal family member. “As a doctor, it’s important to learn how to talk to a family about why they can’t be with a family member at the end. These are hard things.”

The response to COVID-19 has been hampered by a lack of experience and expertise within the federal agencies tasked with overseeing crisis preparations, according to Goldfrank. As a member of the National Academy of Medicine, he and others advocated for creating a national stockpile of ventilators. Their requests were ignored.

“The only way you can ever be prepared for an event of this nature is to be prepared all the time,” he says. “If you wait until the last minute you can’t appropriately serve people. There simply isn’t enough support to do what needs to be done.”

Bellevue Hospital serves everyone, regardless of their ability to pay — the hospital is renowned for its commitment to caring for the poor and disenfranchised. This in-the-trenches public health arena is where Goldfrank has long believed he can do the most good, and not just in the center of New York. For the last decade he’s led Bellevue’s efforts to establish an emergency health system in Accra, the capital of Ghana, which recently experienced its first confirmed cases of COVID-19.

“There is no such thing as a country of greatest risk,” he says. “We are an integrated world — everyone’s at risk. The impact on low- to mid-income countries will be particularly hard.”

Dr. Goldfrank’s passion for preserving the public health is shared by the Bellevue Emergency Department residents. He will caution these young doctors that the stress of wrestling with COVID-19 will continue to echo among them once the crisis has passed. Experience tells him so.

“They’ll have PTSD from this, and will have it for some time,” he says. “I need to help them understand how remarkably well they’re doing and how important their efforts are for society. They are serving people under some very difficult circumstances. This is a powerful plague.”