From the lab to the gym, Devon Rose Leaver strives for peak performance

Devon Rose Leaver’s five years of undergraduate and graduate study in biology at Clark has been packed with classes, research assistantships in two faculty labs, a summer internship near Boston, scientific conferences, and even part-time jobs.

As she works on her master’s thesis, Leaver ’24, M.S. ’25, is reaching for her apex: a spot in a Ph.D. program. In a time of uncertainty for prospective doctoral students, she’s still weighing her options after getting into one program and waiting to hear from others.

She’s interested in studying molecular biology and microbial ecology — the genetics, composition, functionality, and ecology of microbial communities — similar to what she’s studied most recently in the lab of Professor Nathan Ahlgren, a marine microbial biologist and the Warren Litsky Endowed Chair in Biology.

“My diverse experiences in research,” she says, “have pushed me to realize that a Ph.D. program is a commitment to pursuing a dedicated and in-depth approach to a topic. And if you are not fully engaged with that and impassioned by that, it is very difficult to contribute what you would want to contribute.”

“My experience at Clark would be very different if I didn’t have an outlet for my energy and my passion for being outside.”

But graduate-level research is not the only peak Leaver has conquered. The biology major and political science minor reached new heights when she started rock climbing during her sophomore year.

“I was lifting weights, and a friend suggested I try rock climbing. They thought it would click with my brain because you’re trying to figure out the most efficient and creative way to get from point A to point B,” Leaver recalls. “We started climbing together and then we said, ‘We should start a club.’ ”

They did. The three-year-old club officially climbs at Central Rock Gym in Worcester. (Because of liability issues, members pursue outdoor climbing individually, not with the club.)

“I love climbing. When you’re in a city environment, it is sometimes hard to gain accessibility to outdoor experiences,” Leaver says. “That’s why our club, like the Outing Club, the Mycology Club, and other similar clubs are pushing people to go outdoors.

“My experience at Clark would be very different if I didn’t have an outlet for my energy and my passion for being outside.”

Three years in, she has pursued the sport throughout New England, eastern Canada; and the western U.S., including a 600-foot cliff in Colorado’s Eldorado Canyon. Her favorite place to climb is the 60-foot-high Otter Cliff overlooking the ocean in Acadia National Park in Maine.

“I don’t know how many times in your life you get to climb on a shoreline,” Leaver says. “Over five hours from when you start climbing, you see the tide come in right below you.”

Leaping from high school to college

In rock climbing, Leaver has learned to find a patch of solid ground to hold onto, moving from one crag to the other to reach the clifftop.

In her academic work and research, the Pell Grant recipient is similarly driven to take on new challenges, scramble over obstacles, and find stable footing to meet the goals she once believed to be out of reach — while enjoying herself along the way.

Her interest in biology research started in high school in Westchester, N.Y. To learn more about how she might get from Point A to Point B, she worked at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City.

“I loved that experience. That is where research really clicked with me,” she recalls, “because I was interacting with grad students who were really smart, but they also had Pokémon stickers on their desk and liked ‘Dr. Who,’ which was my favorite TV show. They were human, you know — very serious people in lab coats, but they were real.”

“I had a pretty strong feeling I wanted to do a graduate degree, but obviously, you get to college, and you never know what’s going to happen.”

Similarly, Leaver chose Clark because it was on the list of “Colleges That Change Lives” and seemed like a good fit for someone who wasn’t always sure of her path.

“That was very appealing to me as a high schooler who was trying to navigate all the technical boundaries of a university,” she says, “and then after looking into it, I found out that Clark had a lot of private research and that the [4+1] Accelerated Master’s program existed.

“I had a pretty strong feeling I wanted to do a graduate degree, but obviously, you get to college, and you never know what’s going to happen.”

For one, Leaver thought she wanted to study biochemistry and European history.

“Then I shifted gears and did biology and political science because I really love the policy aspects of political science,” she says, “especially because I find there isn’t a ton of overlap all the time between people who do the research and people who write the policy.

“I have had amazing advisors throughout my experience at Clark who have allowed me to connect with the classes and course loads and material that have interested me,” Leaver adds. “I’m happy I chose Clark because it’s definitely a good base for students who might come in and not know what they want to do.”

Building her academic muscles

Leaver became interested in public health when she arrived at Clark in fall 2020 — in the heart of the pandemic — and took Philosophy Professor Patrick Derr’s First-Year Intensive (FYI) course, AIDS to COVID: Ethics and Pandemics.

“It was a great course,” she says. “I quickly learned how relevant policy is to research and vice versa through the constant stream of papers we were researching and writing.”

Her interest in public policy and environmental politics led her to take classes with Political Science Professor Edward Cohen, who became her advisor for her minor.

“I wasn’t sure if I wanted to do public health or environmental science or continue my biology research,” Leaver says. “He was so kind to sit down and show me programs and give me insights and just talk after class. He is a fantastic professor for engaging with students who come from backgrounds different than political science.”

Gaining research experience

Leaver realized she still wanted to pursue biology research, however. One day while working on campus, she struck up a conversation with biology professor, and her soon-to-be co-mentor, Javier Tabima Restrepo, who noticed her double-DNA earrings and encouraged her to pursue research in biology. Having read “Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds, and Shape Our Futures,” Leaver reached out to his colleague, world-renowned mycologist David Hibbett, the Andrea B. and Peter D. ’64 Klein Distinguished Professor of Biology.

“I realized, ‘Wow, there is an opportunity to pursue this really diverse research in a lab,’ ” she recalls.

Her sophomore year, she joined the Hibbett Lab. “David was the perfect mentor, the person I would absolutely suggest for an initial research experience,” Leaver says. “Everything I learned from the Hibbett Lab is very relevant to my current and future work and was incredibly beneficial as a foundation for research.”

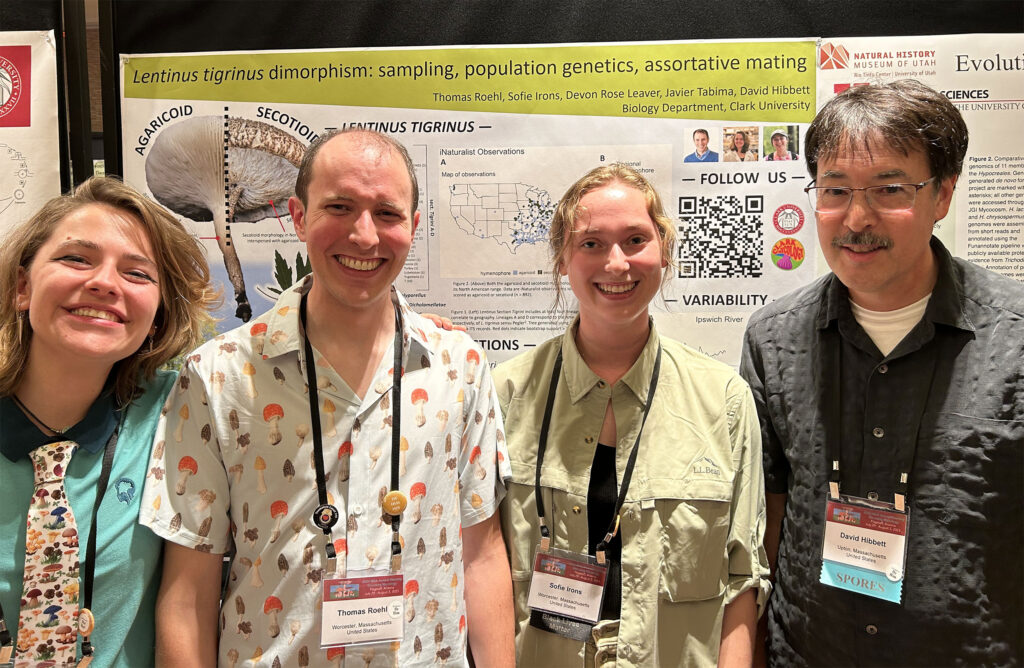

She also worked closely with Ph.D. student Thomas Roehl, who helped her prepare for her first research poster presentation at the national annual conference for the Mycological Society of America. Leaver and her co-presenter, Sofie Irons ’23, M.S. ’24, joined Hibbett, Tabima, and Roehl at the conference in Flagstaff, Arizona, where they also had the chance to hike and forage for mushrooms.

“It was an incredible experience for testing out how to communicate my scientific research efficiently,” Leaver says, “I’m a big advocate of going to conferences. They provide a great exposure experience for students to meet other people, delve more into research, and ask more questions.”

Fine-tuning her biology interests

After taking a class with Tabima on The Genome Project, Leaver became interested in DNA sequencing and processing — the steps following isolation and extraction of the genetic material. They had used data from Ahlgren, a guest lecturer in the class, and Leaver became interested in his work.

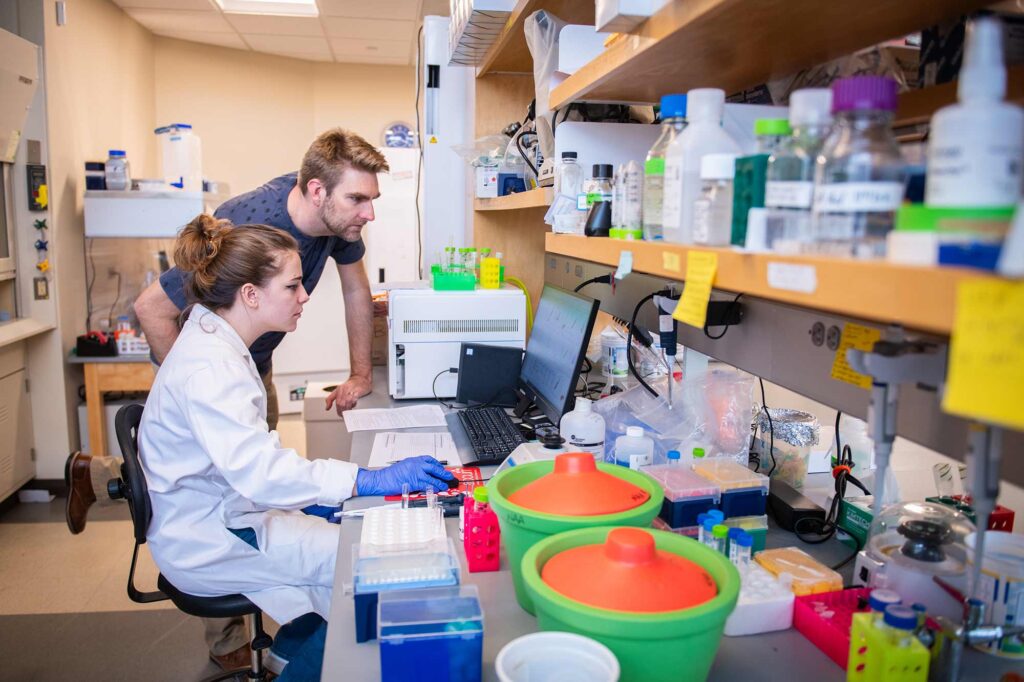

Her senior year, she joined the Ahlgren Lab to work on a $1.1 million National Science Foundation-funded project examining the interactions between the cyanophage virus and their host, Synechococcus cyanobacteria, an important foundation of life in the oceans that produce as much as 15 percent of earth’s oxygen. The research is key to understanding the ocean’s ecosystem.

Leaver master’s thesis draws from the research she conducted in Ahlgren’s lab, where she studied 15 years of water samples gathered from Narragansett Bay in Rhode Island. She gained experience in DNA sequencing and genomics, biostatistics, and bioinformatics. She also took microbiology and virology classes with Ahlgren.

“It’s a bit mind-boggling to think that something that you can’t really see can be majorly impacted by a wide range environmental and/or anthropogenic factors and have major impacts themselves.”

“I really like the work that I do here because it allows me to think about the multiple perspectives of research,” Leaver says. “Sometimes you’re simply observing that an organism behaves a certain way, and other times you’re spending a lot of time going in depth about what that data means.”

But over time, she adds, researchers might “find bigger implications, like uncovering shifts in population dynamics and even how things might move around the ocean because of the shifting climate.

“It’s a bit mind-boggling to think that something that you can’t really see can be majorly impacted by a wide range environmental and/or anthropogenic factors and have major impacts themselves,” Leaver says.

In the little spare time she has, Leaver keeps abreast of science news and history by reading books and listening to podcasts like Science Versus, Ologies, and Stuff You Should Know.

“I have books in my closet that are on anything from the evolutionary history of cognition, to black holes, to the story of Henrietta Lacks,” Leaver says.

A biotech internship: no car, no problem

Leaver has found opportunities to build and refine her knowledge, including through the Harrison Mackler ’07 Summer Research Award for Biology and Biochemistry majors. Last summer, she further expanded her research profile with an internship supported by Project Onramp, which provides access for under-resourced students to land high-quality, paid positions in the life sciences.

She faced one barrier, however. Leaver — who has helped pay her way through college with jobs at Central Rock Gym, a local coffeehouse, and Clark’s chemistry stockroom — doesn’t own a car. She lives in Worcester, and her internship at Remix Therapeutics in Watertown was over 41 miles away.

She didn’t let that stand in her way.

“I invested in an electric scooter,” Leaver says. She took an MBTA commuter train from Worcester to Boston Landing, and then “I scootered to work every single day,” retracing her path at the end of the day.

“I’m a big public transportation person. It’s more efficient than a car and it’s better for the environment,” she says. “But the commute was the hardest part of the internship — having to get up and catch a train at 6:30 a.m. and getting home at 6:30 p.m. every day was a lot.”

In a biomolecular and science lab on the biochemistry team, Leaver worked with cell cultures and assay development, a key step in creating drugs that target certain molecules to fight disease. Remix made sure she had plenty of opportunities to network with scientists in and outside of the company.

“They treated me like an employee, which was awesome, while still providing the safety-like bars and wheels for an intern who was learning things for the first time,” she says.

“I hadn’t done any of that lab work before. Nor had I taken a biochemistry class. So, it was a big learning curve. And everybody was incredibly patient and kind.”

Leaver received advice and support from employees throughout the company.

“I feel like undergraduate school is learning to learn, and then graduate school is learning to think.”

Knowing that she was applying for Ph.D. programs, one scientist coached her, asking a simple, direct question: “Why do you want a Ph.D.?”

She realized she had never before been asked this question so bluntly, but she now has an answer.

“I have a lot of my own questions that I would like to answer and topics that I want to explore,” Leaver says. “I feel like undergraduate school is learning to learn, and then graduate school is learning to think. And I know I have a lot of room to grow in terms of my critical thinking skills and then applying them to a topic that I want to study for five or six years in an in-depth and unique way.”

It’s another summit awaiting her. And she’s ready to climb.

Photos by Steven King (unless otherwise indicated)

Video by Beth Prendergast