Virtual reality. Real-life consequences.

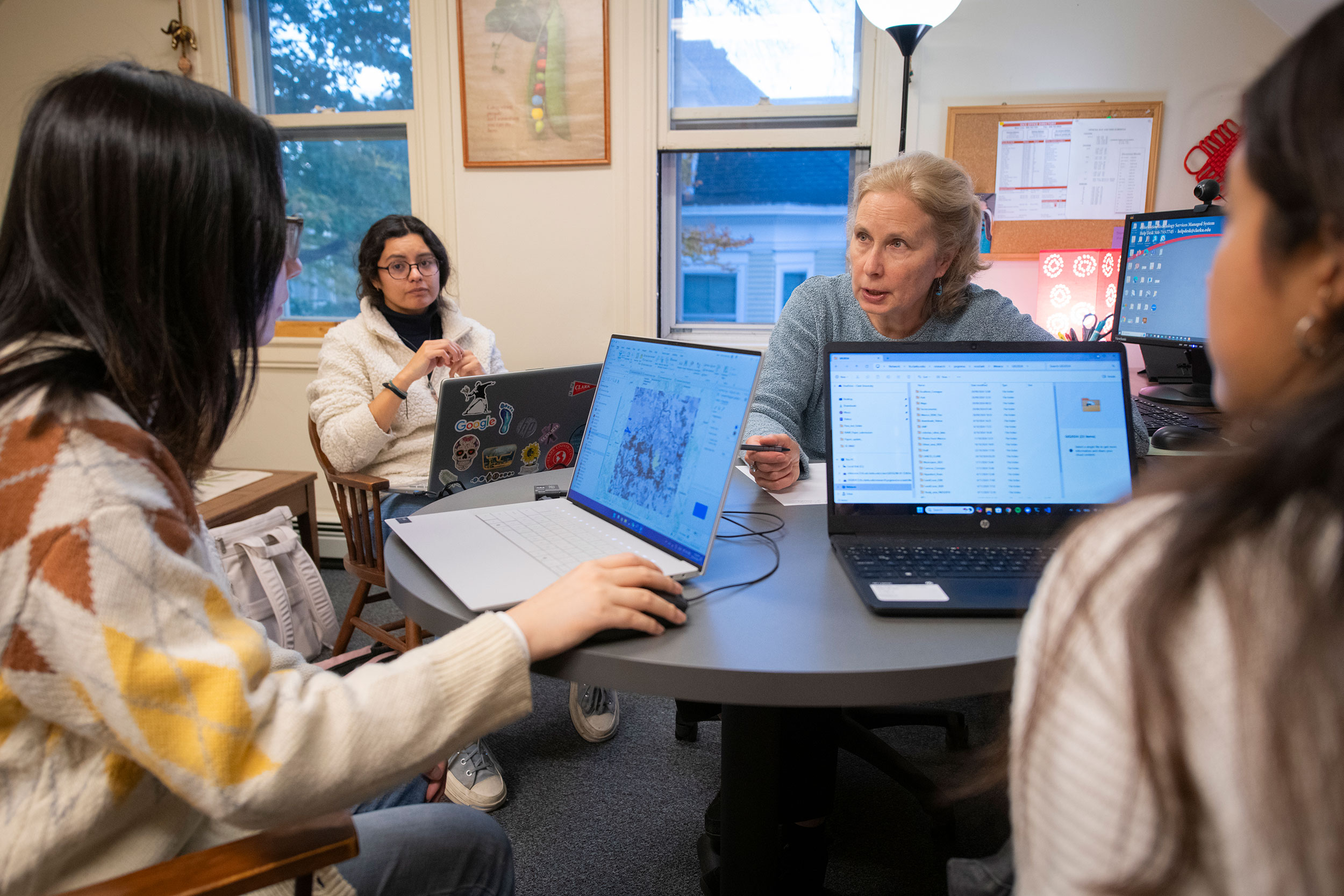

Most Monday afternoons, you can find Professor Yelena Ogneva-Himmelberger and a team of graduate students hard at work in the Department of Sustainability and Social Justice building, poring over geospatial and satellite data related to climate change in Central Mexico.

As part of a four-year, multidimensional research project involving 11 Clark faculty and over a dozen graduate students in several departments, the team is building an online atlas that will allow policymakers and residents of drought-stricken and water-scarce communities to better visualize their future amidst projected climatic, environmental, and socioeconomic challenges.

“For the research community, there are a lot of data out there already,” Ogneva-Himmelberger says. “But for decision-makers and community members, not as much. We want to make this atlas so that it’s easy for them to understand how climate change will impact water resources and the livelihoods of people in the area.”

The atlas will complement an extended reality/virtual reality (XR/VR) platform under development by professors and students in Clark’s Becker School of Design & Technology that will allow residents and policymakers to virtually “inhabit” alternative futures in the year 2050 at local and regional scales.

“We want to make the XR experience completely immersive so that stakeholders — government officials and community members — are free from outside influence for a moment and fully embodied in the experience,” Professor Terrasa Ulm says.

This fall, Ulm is working with Duncan Armstrong ’24, a master of fine arts student majoring in interactive media design, and faculty colleagues Mengliu Lu and Amanda Theinert on visual designs for the platform.

“We want them to be able to visualize alternative futures depending on which policy decisions they pursue,” Ulm adds. “And having access to the data in a meaningful, contextual, and immersive way has been shown to inspire people to make real-world changes.”

Tim Downs, professor in the Department of Sustainability and Social Justice, hopes both interactive technology projects encourage local and federal governments in Mexico, as well as academic researchers, to collaborate with local communities in charting a sustainable future.

“What has been sorely missing in modeling efforts are models at human scale, with ways to grasp what is at stake — literally the future of our biosphere — but with hope, concerted effort, and joy, not despair,” says Downs, principal investigator of the project focused on climate-change impacts in Central Mexico and how they relate to the long-term water crisis.

Funded by a $1.5 million grant from the National Science Foundation’s Partnerships for International Research and Education Program, the project involves researchers from Sustainability and Social Justice, the Becker School, and the Graduate School of Geography, along with their peers at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM).

Besides the atlas and XR platform, research teams are focused on developing a systems model (a methodology using mathematical formulas to inform strategic policymaking), supporting communities’ 3D printing and deployment of affordable weather stations and mosquito traps, partnering with schools to develop climate-related educational programs for youth, and working with communities to gather the data on impacts that inform the various initiatives.

Living and learning in Mexico

Funded by the NSF grant, Clark graduate students have played a significant role in the project, Downs says, working closely with communities in Central Mexico to gather data.

For the first half of 2024, six master’s students from the Department of Sustainability and Social Justice lived in the Mexico City area researching the impacts of the water crisis and climate change. They included Josaphat Barcenas-Argueta, Milagros Becerra Zambrano, Mattie Carroll, Mónica Muñoz Miranda, Fátima Oseida, and María Salazar, representing programs in International Development, Geographic Information Science (GIS), and Environmental Science and Policy.

Last spring, Muñoz Miranda and Becerra Zambrano — now second-year GIS majors — interviewed academic researchers and government climate specialists about the information that would be most relevant for users accessing the online atlas.

“We want the atlas to be co-created and co-owned by local communities and government partners,” Downs says. “It’s not the traditional model where the academics produce it, and it’s used only by government agencies.”

This fall, using ESRI’s ArcGIS Hub digital mapping and analytics platform, Ogneva-Himmelberger is working with Muñoz Miranda, Becerra Zambrano, and two first-year M.S.-GIS students — Xiao Han and Tevita Soqo — to integrate the geospatial and satellite data into the atlas. Users will be able to select data regarding current and future climate conditions, water resources, land cover, elevation/slope, soils, population, and people’s health and livelihoods.

Supporting 3D-printed weather stations

Meanwhile, Sustainability and Social Justice Professor Morgan Ruelle and Geography Professor Abby Frazier are leading a team of graduate students to support communities in assembling and using inexpensive, accessible 3D-printed weather stations to monitor the impacts of climate change.

The project is drawing from Frazier’s experience in Hawai‘i, where she and her research colleagues oversaw installation of 100 weather stations to provide communities with the climate data necessary to make informed decisions.

Three M.S. students in Environmental Science and Policy — Luke Trefry, Valeria Obregon Diaz, and Catalina Cuervo Maldonado — are working with Ruelle, Frazier, and Sustainability and Social Justice doctoral candidate Ravi Hanumantha this semester at Clark to learn how to assemble weather stations so they can support communities in Mexico.

Clark has donated 3D printers to two pilot communities with whom it is collaborating: Miravalle in Iztapalapa, a borough of Mexico City, and Valle de Bravo, a town 100 miles west of the city and home to a major reservoir. The collaboratives will create weather stations, along with traps to capture mosquitoes that carry the dengue fever pathogen; dengue is driven by a warming climate, and is on the rise, according to Downs. The temperature, rainfall, mosquito, and dengue incidence data will feed into the online atlas, systems model, and XR platform, he says.

The team’s ongoing work also will incorporate the region’s first water balance model for future climate-change scenarios. Hanumantha spent more than five years developing the fundamental model, Downs says, and is set to graduate from Clark this fall.

Next spring, three graduate students — Obregon Diaz, Cuervo Maldonado, and Kwabena Antwi, a third-year Ph.D. student in geography — will live in Mexico, conducting research with communities and UNAM peers as they gather data on impacts. They will install the weather stations, traps, and other monitoring equipment to gauge air and water quality.

As part of his doctoral research, Antwi will work with local communities to examine the impacts of climate change and water insecurity on smallholder farmers and agriculture.

Surveying communities

Last summer in Mexico, international development master’s students Mattie Carroll and Fátima Oseida surveyed more than 60 residents about water issues and climate-change impacts. With Sustainability and Social Justice Professor Cynthia Caron, Obregon Diaz, and Cuervo Maldonado, they are analyzing the interviews this fall.

The Becker School team will integrate the survey data into the XR platform, according to Downs, along with systems dynamics modeling developed by Hanumantha that is being extended by Antwi.

“Narrative is at the heart of any virtual or extended reality experience,” Ulm says, “so we’re excited to incorporate the community members’ personal stories.”

“Everything we’re trying to do is community-centered,” Downs adds. “It’s centered on the places where people are experiencing these impacts.”

Study climate change

Explore our programs from the perspective of our students.