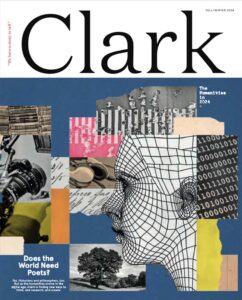

Clark University Magazine

A Legacy in Bloom

Most people who walked by the silver-haired woman planting tulips and geraniums around campus did not know her, if they noticed her at all.

Given Alice Higgins’ innate humility, her anonymity came as no surprise. Kneeling in the soil with a trowel in hand was simply her quiet expression of a love as sturdy as a fieldstone foundation and as delicate as a tulip petal. The object of her devotion: Clark University.

Higgins is a consequential figure in Clark’s history, a longtime leader and benefactor known for a dynamism that matched her generosity. In 1962, she became the first woman elected to the Board of Trustees, and from 1967 to 1974 served as the first female chair of a board of trustees at an American research university. She was instrumental in planning and fundraising for signature University structures, like the Goddard Library and Kneller Athletic Center, and looked fabulous in a hardhat at groundbreaking ceremonies. She had presence.

In 1986, seizing upon an idea proposed by then-Provost Leonard Berry, Higgins made a $1 million gift to establish the Higgins School of Humanities—a channel for developing innovative programs, supporting compelling faculty research, and generating the kinds of conversations that bridge disciplines and give space for disparate, sometimes conflicting, ideas.

“Alice said to me several times that there wasn’t any problem that couldn’t be solved if people would just sit down and talk to each other,” says Virginia Mason Vaughan, professor emerita of English and the school’s first director.

The conversations and explorations persist, albeit under a new banner. Thirty-eight years after its founding, the Higgins School for Humanities has been renamed the Alice Coonley Higgins Institute for Arts and Humanities. The essence of the Higgins mission is to promote “humanistic inquiries and practices that are crucial to our development as intellectually curious, socially engaged, and ethically oriented beings.” Those inquiries and practices continue, with added attention to how modern technologies and environmental changes shape our awareness of social complexities and challenges as they evolve and accelerate over time.

“The Higgins Institute can be described as bringing the world to Clark, with empathy,” says Director Matt Malsky. “Everything is done with humanity at the forefront. Not just humanities, but humanity.”

The initial iteration of the Higgins School focused on internal audiences, Vaughan recalls. Grants were distributed to support faculty research and enrichment activities for students. The school also hosted faculty-led seminars, often pairing professors from different departments who were interested in a common area of inquiry. The school launched the African American Intellectual Series, the brainchild of English Professor Winston Napier, and fostered faculty dialogues inside the Carriage House on Woodland Street, where the school was then based (it would later be relocated to Dana Commons).

“I made it a stipulation that if you got a substantial grant, you had to give a lecture about your research,” Vaughan recalls. “My first goal as director was to try and make the work of humanities scholars and students at Clark more visible.”

TIMELY TALKS

The Higgins Institute for Arts and Humanities boasts a long history of bringing to campus luminaries from a variety of fields to speak on matters shaping our world. A brief selection:

Author, activist, and a member of the famed Chicago Seven arrested for their part in the protests at the 1968 Democratic Convention, Tom Hayden transfixed the audience in Dana Commons as he recounted his role in the anti-war and civil rights movements of the 1960s. “It was a time of pure beauty and uprisings,” Hayden recalled. “We thought we could change the country and the world.”

Nicholas Carr, author of The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains, revealed how our online existence is rewiring our minds, replacing deep thought with information overload, and overruling attentiveness with a steady stream of interruptions and distractions. In stark terms, he warned we are losing our capacity for deep, sustained thought and are becoming “suckers for irrelevancy.”

“I did not grow up in a world where I ever felt safe,” transgender rights activist Janet Mock told an audience packed into Jefferson 320. In a dialogue with Amy Richter, director of the then-Higgins School, Mock recounted the challenges of growing up multiracial, poor, and transgender in America and the need to make room for oneself in the world. “Listen to yourself,” she advised students.

Former U.S. Poet Laureate and Pulitzer Prize winner Natasha Tretheway read from her works, delving into matters of race, family, history, and the moving target that is our evolving perception of all three. Her selections combined personal experience and the intimacy of memoir with national history and the grand sweep of social and cultural change to “find out something deeply ingrained.”

Author and historian Annette Gordon-Reed, whose investigation into the relationship between Thomas Jefferson and the enslaved Sally Hemings earned her the Pulitzer Prize, spoke at Clark about the controversy surrounding the findings. “This story is of incredible importance to us in thinking about the history of race in this country, and the way history itself is written.”

Stanley Pierre-Louis ’92, the CEO and president of the Entertainment Software Association, returned to campus as part of the Higgins “Fair Game(s)” symposium to discuss the societal impact of video games and the robust career outlook for students enrolled in game design programs at Clark. “They are literally always hiring in our industry,” he said.

Sarah Buie, professor of design in the Department of Visual and Performing Arts, took over as director of the Higgins School in 2004 and amplified the conversation.

In 2005, Buie and William Fisher, then director of the Department of International Development, Community, and Environment (now the Department of Sustainability and Social Justice), led a group of 16 faculty and staff in navigating the application process when the Ford Foundation made a call for their new and timely program, Difficult Dialogues. Out of 720 applicants, Clark was among the 27 colleges and universities nationwide to be funded in December 2005. The Clark community embarked on a distinctive version of Difficult Dialogues in November 2006, making it the signature endeavor of the Higgins School for more than a decade.

Difficult Dialogues encouraged participants to address some of the thorniest issues of the day in ways where the ability to listen deeply was as highly valued as the expression of one’s own thoughts. The symposia, lectures, workshops, concerts, and exhibitions—many of them held in Dana Commons’ Higgins Lounge (known affectionately as “the Fishbowl”), which Buie designed and furnished—inspired participants to communicate thoughtfully and civilly across differences, no simple task in a polarized age.

Participants explored a host of topics, examining issues of race, gender, the state of our democracy, religion, our changing Earth, and the use and misuse of power, while the precepts of respectful, fruitful dialogue were further incorporated into dozens of Clark courses. The fall 2010 theme of “Slowing in a Wired World” gave such fresh focus to modern society’s reliance on instant communication that The Boston Globe dispatched a reporter to campus to write about it.

“EVERYTHING IS DONE WITH HUMANITY AT THE FOREFRONT. NOT JUST HUMANITIES, BUT HUMANITY.”

During Buie’s transformative tenure, exploration and reflection on the human-environment relationship and the climate crises became a focus of many Difficult Dialogue symposia—bringing together almost 30 faculty with related research and teaching expertise.

As her term came to an end in 2012, Buie’s work at Higgins laid the groundwork for the creation of the Council on the Uncertain Human Future, initially funded by the Mellon Foundation through the Consortium of Humanities Centers and Institutes. The early faculty councils led two campuswide climate teach-ins in 2015 and 2016 that brought together hundreds of students, faculty, staff, and visiting speakers from across the disciplines, among them writer and visionary Naomi Klein, for day-long considerations of the evolving environmental and social challenges facing us.

The council’s work has expanded to include hundreds of members representing prominent institutions across the U.S. and in several countries and served as the impetus among faculty for A New Earth Conversation (2017-23) at Clark, a campuswide curriculum initiative that brought a fresh approach to climate education.

“What does it mean to educate, to create a space of learning and nurture, in these turbulent, revelatory times?” Buie has asked. “Might we meet our students in the realities of where we are, and what it means? Might we help seed a life-supporting society?”

It was standing room only in the Fishbowl when filmmaker Jennifer Potts held the Worcester premiere of her original documentary chronicling Afghan refugees who were making new lives for themselves in the city. Family members, friends, Worcester officials, and students from local schools gathered to watch the film—which was translated into four different languages in real time—and then engaged in a wide-ranging discussion about what they’d just seen and their hopes and plans for the future.

The screening, held under the auspices of the now-Higgins Institute in partnership with the Worcester Arts Council, underscored the Institute’s emphasis on “public humanities,” which, as Matt Malsky puts it, “we’re bringing to the masses.”

“We find the fault lines where interesting conversations, discussions, and arguments happen,” Malsky continues. “Higgins has been the conduit through which Clark participates in these broader conversations happening off campus.”

The public humanities component joins the digital humanities and environmental humanities as the three pillars on which the Institute is shaping its endeavors today and in the near future.

The Higgins research collaboratives, beginning with the African American Intellectual Series and finding momentum with Early Modernists Unite, are exploring how traditional humanities can mesh with technologies to enhance research capabilities and bring fresh academic approaches to a generation of students who are native to the digital universe.

Partners from Computer Science and the Becker School of Design & Technology have been working with humanities faculty on ways that databases, imaging tools, and augmented reality (AR) and extended reality (XR) technologies can enhance the appreciation of the humanities. The Higgins Institute recently received a $500,000 Sherman Fairchild Foundation grant to create an Interactive Arts Faculty Collaborative to support this work.

“We are a liberal arts school, but part of the liberal arts will have to be about embracing technology that is in service to the liberal arts and reflects the multiple ways that people experience humanistic subjects,” Malsky says.

“WE NEED MANY DIFFERENT VOICES.”

Environmental humanities, a mainstay in the Higgins Institute, have taken on even greater urgency as Clark prepares to open its School of Climate, Environment, and Society in fall 2025. Last semester, Higgins and A New Earth Conversation announced four faculty fellows in English, geography, history, and languages who will develop courses that will explore climate challenges from a humanistic perspective.

“We’re looking to build communities of practice,” Malsky says. “And to do that, we need many different voices.”

Amy Richter, professor of history and a former director of the Higgins School, says one of the greatest joys of the Higgins directorship is saying “yes”—to faculty research grants, to distinctive programming, to bringing compelling speakers to campus. “When Sarah was stepping down, she told me, ‘Being the director of the Higgins School is the best job on campus.’ She was right. I don’t think there are many places here where your job is fundamentally to say yes.”

The original “yes” was delivered by Alice Higgins in 1986 when she was asked to consider supporting a new humanities initiative. With the renaming to the Alice Coonley Higgins Institute for Arts and Humanities, Clark has thrown its arms around the legacy of its benefactor.

“We’re at the tail end of a moment when people who actually knew Alice are still on campus, and I think it’s important that we keep her front and center,” Malsky says.

Higgins, who passed away in 2000, surely would have reveled in the growth and direction of the institute that bears her name. In 2011, to observe the then-Higgins School’s 25th anniversary, a celebration was held to honor her for making possible the innumerable innovative seminars and public programs, conferences, faculty research projects, exhibitions, and community conversations.

The title of the event was succinct, composed of three words feting a special woman for her vision and philanthropy to build an institution-within-the-institution, a hub for the frank exchange of ideas and a vessel to reimagine how we engage with the world.

“Thanks to Alice.” ▣