As Austria celebrates ‘Bruckner Year,’ Clark scholar reveals composer’s complex history

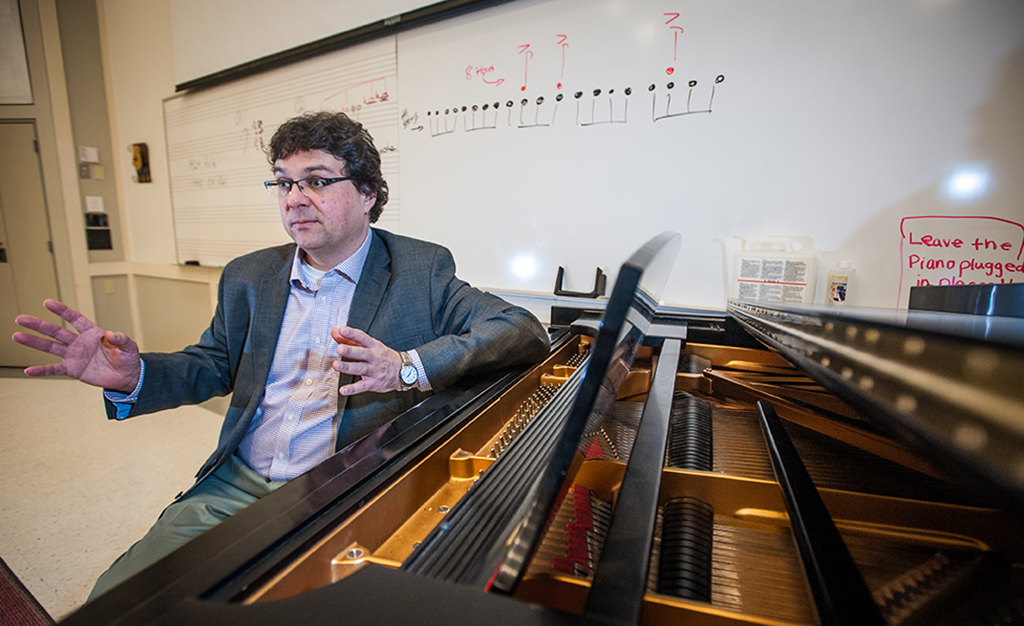

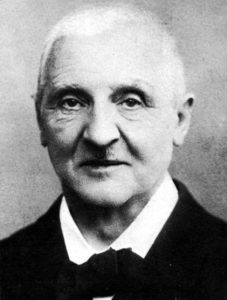

Austria has declared 2024 as “Bruckner Year,” celebrating the 200th anniversary of the birth of its noted 19th-century composer Anton Bruckner. As the festivities ramp up, Clark University Music Professor Benjamin Korstvedt is hitting a career high note as one of the world’s foremost authorities on the composer, born Sept. 4, 1824, in a village near Linz, Austria.

“Bruckner has retained a secure place in the symphonic repertory,” Korstvedt once summed up in The New York Times’ Arts section. “And today many experience a combination of spiritual depth and intellectual intensity in this music that uncannily suits our postmodern condition.”

In April, Korstvedt gave the keynote address for an international conference sponsored by the Austrian Academy of Sciences. In “Bruckner and his Doppelgängers: Scenes from an Afterlife,” the Jeppson Professor of Music at Clark laid out the contradictory images of the composer, who “left few personal accounts of himself.” What is known of Bruckner, he says, comes mostly from secondhand accounts “ranging from sarcastic to sympathetic.”

For the title of his keynote, Korstvedt looked to an unlikely source: Naomi Klein’s 2023 book, “Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World,” in which the environmental activist explores how social media posts have mistakenly identified and attacked her as Naomi Wolf, the best-selling feminist author of 1991’s “The Beauty Myth” who is now regarded by many as a conspiracy theorist.

“Klein became keenly aware that such a doppelganger can — as we say — ‘go viral’ and take over the public image of a person and their work even when it diverges widely from reality,” he says. “The key point Klein makes is that these doppelgangers can develop an independent existence that at times supplants the actual person they claim to represent.”

A devout Catholic’s music is appropriated by Hitler

Korstvedt sees Bruckner as having faced a similar doppelganger predicament. Over the years, the composer has been depicted in many different ways — as a misunderstood genius, a Catholic mystic, or even a dangerous musical radical. Yet Austria’s 19th-century cultured elite, who did not recognize Bruckner’s musical genius during his lifetime, generally saw him as a “bumbling, rustic character from out in the provinces who was not very sophisticated” who could never truly fit into the urbane social world of Vienna.

During his lifetime Bruckner, who died in 1896, struggled to achieve performances of his symphonies, but by the 1920s he had emerged as one of the most avant garde composers of the symphony, Korstvedt says.

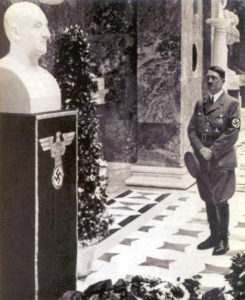

That didn’t last long. Bruckner’s reputation became tarnished once Adolf Hitler — who also had been born in Linz near the German border — claimed the composer as a fellow German.

During the Nazi era, “Bruckner was heavily appropriated as a symbol of German art and music and also of the supposed unity of Germany and Austria,” Korstvedt says. “Hitler took a great interest in Bruckner’s music, and Bruckner became a symbol of German nationalism.”

In a 1937 ceremony at the Walhalla temple, Germany’s “hall of fame” in the Bavarian city of Regensburg, Hitler celebrated the installation of his commissioned sculpture of the composer.

Critical fallout against Bruckner lasted until the 1950s and ’60s, according to Korstvedt, when the popularity of high-fidelity stereos and recordings brought new appreciation for the intense symphonies of Bruckner and his younger composer friend Gustav Mahler.

“Their music was, and is, a favorite of people who are audiophiles. It’s good music to enjoy in stereo,” says Korstvedt, whose authoritative notes accompany SOMM Recordings’ release of Bruckner from the Archives, a six-double-CD-volume series, celebrating the 200th anniversary of Bruckner’s birth.

‘The Bruckner Problem’

In fall 2024, Oxford University will publish Korstvedt’s book, “Bruckner’s Fourth: The Biography of a Symphony.” It’s the culmination of his research into a musical work that perhaps best defines what scholars call “the Bruckner Problem.”

For years, musicologists have disputed the authenticity of various versions of Bruckner’s works, especially his Fourth Symphony. During his lifetime, most of his symphonies were published with his approval, but in the 1930s scholars advanced the argument that these publications had been inappropriately edited by his friends and students, Korstvedt says. As a result, modern editors decided to publish only the “original” versions of his symphonies, even though many of these had not been published by the composer.

Korstvedt’s interest in Bruckner’s music — which led to his lifetime career as a musicologist — began shortly after he graduated summa cum laude as a music major from Clark in 1987. Browsing through the 99-cent bin in a record store, he serendipitously ran across a couple of Bruckner albums and decided to buy them.

Upon listening, “I was really captivated,” he recalls. “It’s such interesting music, with so many innovative aspects, and it’s intensely expressive and dramatic.”

Upon listening, “I was really captivated,” he recalls. “It’s such interesting music, with so many innovative aspects, and it’s intensely expressive and dramatic.”

A few years later, he focused on Bruckner’s complex music and complicated history for his dissertation at the University of Pennsylvania.

“I became aware of some striking contradictions in the historical evidence as well as documents that had been neglected, particularly pertaining to Bruckner’s Fourth Symphony.” The version of the Fourth published during Bruckner’s lifetime, Korstvedt says, “was commonly believed to have been ‘mutilated’ by editors and possibly even produced without his awareness or agreement.”

This interpretation first emerged within Nazi Germany, which added to Korstvedt’s suspicions. “The more I delved into it, the clearer it became to me that a lot of the scholarly work was strongly shaped by the ideological context” of Nazi Germany.

Unraveling a musical mystery

Korstvedt soon became immersed in unraveling the mysteries surrounding the entire matter. As part of his doctoral research, he first traveled to Austria in 1993 to examine photographs of a crucial but long overlooked document from Fourth’s compositional process: a copy of the score prepared by Ferdinand Löwe, a former student of Bruckner’s who later became a leading conductor.

The score has a fraught history. It was made available to a sympathetic scholar in 1940. But since Löwe and his family were identified by the Nazis as half-Jewish, the issue quickly became a cause célèbre. But given the great political investment in Bruckner’s music at that time and place, the scholarly debate was quickly silenced.

After the war, the manuscript was returned to the Löwe family, but then seemed to vanish. A decade ago, it reappeared at an auction but since then its whereabouts have remained unknown. Only the set of photographs made in 1940 remain accessible.

Korstvedt’s research convinced him that this score proved that the 1888 version of the Fourth was not a corruption of Bruckner’s wishes but rather a clear expression of his final intentions. It reveals that “Bruckner had worked over the score closely and made many of the key changes. He was totally involved in the process.”

Korstvedt’s revelation made waves among Bruckner scholars. “There was quite a bit of resistance to it,” he recalls, “and this persists in some circles.”

But his argument won over a key player: the managing editor of the Bruckner Collected Works, the late Herbert Vogg. He asked Korstvedt to prepare a new critical edition of this version of the Fourth Symphony. Korstvedt’s new edition of the Fourth, which has been performed across the world, fostered new insights into the composer’s musical thinking and creative process.

In a nod to Korstvedt’s contributions, The New York Times described Bruckner’s Fourth as “something of a work in progress” because of edits and tweaks by “followers, publishers and scholars. … The burden is on musicologists and conductors to decide which iteration is the most authentic, or just the best.”

More recently, Korstvedt collaborated on a major recording project with the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra that won the 2022 International Classical Music Awards’ Best Symphonic Recording category. The four-disc recording features three versions of Bruckner’s Fourth, including new editions edited by Korstvedt, who also wrote the accompanying essay.

Bruckner’s music and the sublime: a ‘heightened sense of consciousness’

The Fourth’s complicated history may intrigue Korstvedt, but his favorite Bruckner symphony is the Eighth. “The Eighth plunges into some very great emotional depths,” he observes, “and the overall sweep of that symphony takes the listener on a great journey through all sorts of different emotions and conflicts to a very compelling resolution.”

In his first book about the composer, “Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 8” (Cambridge University Press, 2000), Korstvedt writes, “Listeners often sense something transcendent in Bruckner’s symphonies, and many refer specifically to the sublime character of his music.”

Bruckner’s music, above all the Eighth, epitomizes 18th-century German philosopher Immanuel Kant’s idea of the “sublime, a state of mind that is induced by extreme experiences, whether natural phenomena like mountains or powerful thunderstorms or the ocean, or great artworks,” explains Korstvedt, who team-teaches a class, The Ethics and Aesthetics of the Sublime in Music and Art, with Philosophy Professor Wiebke Deimling. “And with music, part of what’s involved is an effect of sensory overload that challenges your powers of comprehension, and through that challenge, a heightened sense of consciousness emerges.”

As Korstvedt told his audience in Austria last month, “Bruckner’s music is big in spirit, rich in content, deep in implication — and these qualities are the source of much of its greatness. His music truly does contain multitudes — and that is exactly why it has the power to fascinate us, to be reborn in different ways every time it is performed and heard — even now, generations later.”