When the nuns of Bogotá needed assistance to lift the city’s poorest citizens out of poverty, John Dobson accepted the challenge.

When the nuns of Bogotá needed assistance to lift the city’s poorest citizens out of poverty, John Dobson accepted the challenge.

Because it was good work. And because you don’t say no to the nuns.

The associate professor of practice in Clark’s School of Management had been invited to Pontificia Universidad Javeriana in 2015 to present at an entrepreneurship conference, where he learned of the project being led by the Sisters of the Epiphany of Marie Poussepin in one of the Colombian capital’s roughest sections, San Cristóbal del Sur.

Dating back to the 17th century, the religious order had been helping struggling mothers and grandmothers gain financial autonomy within this sprawling city that today numbers more than 7 million people. But their more recent efforts, noble as they were, had fallen short. Families still went hungry.

“Possibilities can be discovered, even when they might not seem to exist.”

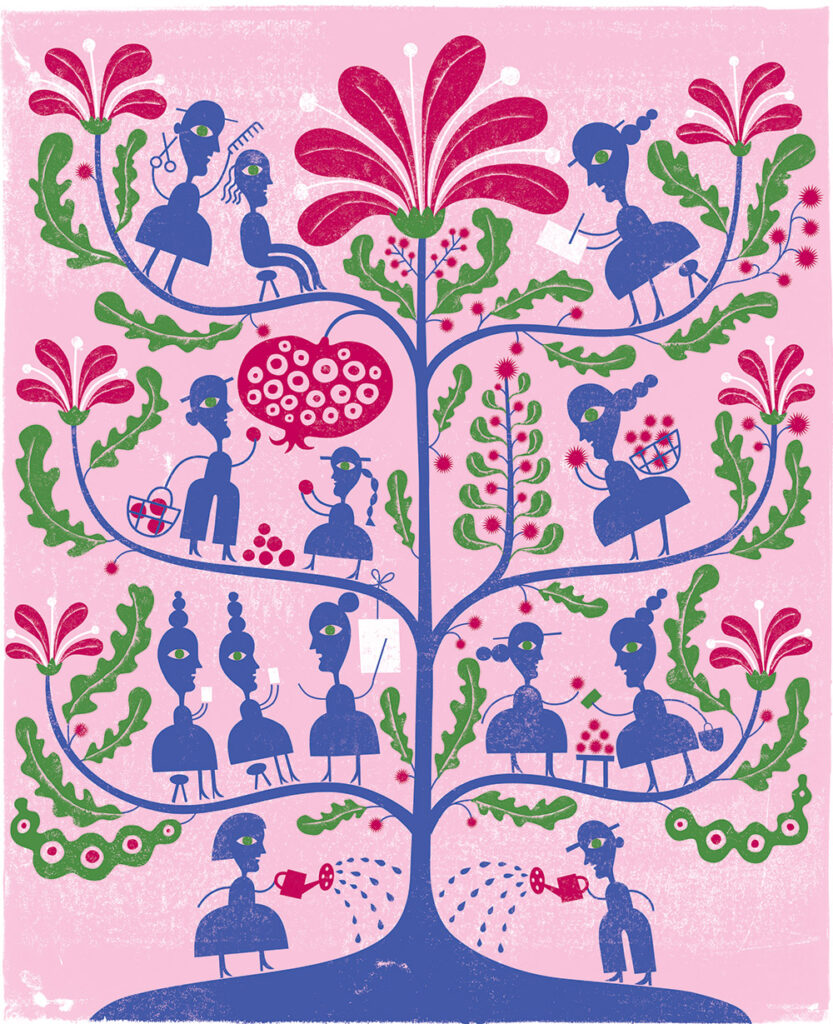

Impressed by the nuns’ tenacity and moved by their mission, Dobson visited San Cristóbal del Sur, where he partnered with the sisters to develop workshops that allowed local women to launch and grow small home-based businesses. Most crucially, the women cultivated backyard gardens to supplement their families’ nutritional needs and supply a sustainable source of household income from the sale of surplus

produce.

“Most of the women were housebound grandmothers who were caring for their grandkids, but now they could be earning their own money,” Dobson recalls. “The real connection here wasn’t about farming. It was about empowerment.”

He knew the project was working when a Javeriana faculty member noted that the grandmothers weren’t keeping their books. “I found out that they appreciated having a little bit of money to buy their grandkids a birthday present or some school supplies, but they were purposely secretive about the money because if they told their neighbors, they’d be envious, and if they told their kids, they might want it. These little gardens in the backyard had given them agency over their own lives.”

Since 2015, Dobson has returned to Colombia annually (except when covid made travel impossible), some years bringing Clark students with him to tend the backyard Bogotá gardens alongside the grandmothers. In 2018, he established the dyme (Develop Your Model of Entrepreneurship) Institute, which partners with schools and centers across the globe to offer aspiring business owners in developing economies access to a world-class entrepreneurial education—a boon in places where traditional funding and educational resources can be scarce.

The urban farming project in San Cristóbal del Sur earned the attention of leaders of the Bogotá Botanical Garden, who in 2020 approached Javeriana and Dobson about collaborating with them to improve the dismal rate of return on the thousands of citizen farms that the Garden had helped launch throughout the city. At the time, only five families from within the Botanical Garden’s network of 10,000 farms were realizing a minimum livable wage of about $500 a year.

To scale up efforts, Dobson organized a series of workshops where he and colleagues from various universities—including, this past May, School of Management professors Steve Ng and Lawrence Norman (see They mean business, below), as well as experts from his professional network—train about 120 farmers and technical staff from the Botanical Garden over the course of a week. The participants learn the entrepreneurial skills and tools needed to generate a steady income—everything from financial management to marketing strategies to customer relations.

The workshop attendees then return to their city neighborhoods to share best practices with other farmers. The visiting experts also pair up with local faculty and technical staff to “take it to the field” and work with local residents to turn their lessons into tangible benefits.

The “train the trainers” model has borne fruit: Within a year and a half of the program’s launch, more than 250 families are earning a livable wage from their agricultural pursuits. And their success has attracted additional key stakeholders. Organizers of botanical gardens in other Colombian cities have expressed interest in attending the workshops, and the mayor of San Cristóbal has signaled his support for the project.

The impacts of the DYME projects are far more than monetary for these citizen farmers.

“This is about building social capital within their community rather than simply profit maximization,” Dobson says. “We’ve seen over and over that these women gain a central and important role in the community.” The goal, he says, is to “create a climate of innovation that is economically, socially, and environmentally sustainable” and capable of elevating the circumstances of people who typically get by on as little as $2 a day.

The Mexico-born Dobson brings deep entrepreneurial experience to the enterprise. He started a wholesale and retail import business in Nova Scotia at age 18, growing it into a multimillion-dollar company specializing in the sale of Mexican handicrafts. After 25 years, he sold the business in 2007 to begin a career in academia. His approach at Clark has typically been to “throw away the textbooks” and guide students through the process of developing their own business ventures, often accomplished by “disrupting norms” that turn inspiration into payoff.

Dobson has plentiful examples of successful Bogotá disruptions. He recalls a group of six families who were collecting and selling about 50 pounds of organic waste each month. They attended a DYME workshop, learned techniques for pitching their product door to door, and immediately sold 50 pounds in a day. They then connected with a farmer on the outskirts of Bogotá who bought 1,000 pounds.

A DYME microloan program allowed one woman to purchase a blender, table, and cooler, dramatically increasing the production and sales of her homemade arepas, widely considered the national dish of Colombia. Similar to a tortilla, but much thicker, it is filled with beans, meat, eggs, and cheese. The arepa is a typical meal for the working poor.

Another Bogotá mother, loan in hand, bought 30 chickens, which became the starting point for her own catering business.

“The program gives urban farmers the confidence to apply their ideas, and believe in their skills, and work,” says Leslie Aguirre, an entrepreneurship lecturer at Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. “They learn that more than theoretical tools or financial aid, they need to trust their field of knowledge and take simple steps to keep an initiative on track. Some of the best ideas come from the least educated but the most observant.”

Dobson remains in steady contact with his Bogotá partners and has conducted Zoom classes with the indomitable Sisters of the Epiphany to continue pressing for solutions to the obstinate challenges facing the poorest neighborhoods. He remembers his impatience with one nun who had developed a business plan for providing essential services but who had been sitting on it for five years as she held out for government funding that was unlikely to come. Some tough love was required.

“I told her, ‘If you don’t implement something by the end of the week, I’m going to kick you out of the class,’” he recalls. “My argument was: Think of all the people who could have been helped as you waited for the perfect plan to take shape—it’s never going to be perfect. So, she contacted a hairdresser and they went to a street corner where they washed and cut the hair of the homeless. Then she recruited a nurse practitioner to conduct basic health clinics and community outreach. She was always willing to do the necessary hard work but didn’t understand that you don’t need perfection before you start something.”

Dobson’s lessons continue to resonate with Bogotá’s women of faith. When asked to share her experiences applying the DYME model to elevate the underserved, Sister Alba Leonor Carvajal Carrillo of the Dominicans of the Presentation Charity serves up terms like “breaking mental paradigms” and “stimulating interdisciplinary volunteerism” with the casual authority of a seasoned mba professor. Yet the underlying truths, she notes, are simple, potent, and universal.

“Possibilities can be discovered, even when they might not seem to exist,” Sister Carrillo says. “Maintaining a consistently positive attitude, seeing failures as opportunities to achieve better results, and overcoming selfishness and personal interests help group ventures avoid failure.”

She points to one of her favorite success stories—Machetunas Arepas. Using the dyme model, two women, working with a $50 loan from Dobson, developed a business making and selling arepas and other corn flour-based products. The nuns lent their kitchen, with one woman walking 90 minutes each morning to work on the project.

“The real connection wasn’t about farming. It was about empowerment.”

Within the first month, the women paid back Dobson. Within three months, Machetunas Arepas had generated a profit of $450, increasing the women’s income from zero to $2.50 a day, a life-changing sum in a place bullied by poverty. They later expanded operations to include five families and moved production from the nuns’ kitchen to a rented space. Today the business continues to thrive and grow.

Eden B. Crucillo, director of international relations at Colegio de Estudios Superiores Administracion (CESA) in Bogotá, has partnered closely with Dobson over the years, and their challenges do not abate. She notes that among Latin American countries, Colombia has one of the highest rates of economic inequality, and unemployment persists at stark levels.

“Our role is to have an impact in a way that will strengthen the ecosystem for social entrepreneurship,” she says. “Because of John’s large network, he’s able to bring in international professors to share their expertise, their time, their resources.

“Now we’re engaging our students to design packaging materials for the products; students are helping with marketing efforts. These are students from privileged backgrounds who are engaging with these urban farmers and learning from them. And it’s all because of the methodology imparted by John.”

Bogotá is a prized destination for migrants from neighboring Venezuela who stream into the city hungry for opportunity. Dobson has worked with Venezuelan educators to develop best entrepreneurial practices, but because of the security challenges in that country, representatives from 12 universities traveled to Cucuta, Colombia, to receive their training.

He’s also a presence in his native Mexico, teaming with En Acción, a network of over 100 nongovernmental organizations, to devise methods for better serving their clients. The latter assignment sends him into Mexico City where the Oblate Nuns of the Virgin Mary escort him through neighborhoods with a reputation for violence.

He’s never been bothered nor feared for his safety, he says, because what holds true in Mexico City is the same that holds true in Bogotá: “You don’t mess with the nuns.”

ILLUSTRATIONS BY MELINDA BECK

THEY MEAN BUSINESS

In May, I was fortunate to have traveled to Bogotá, Colombia, with DYME (Develop Your Model of Entrepreneurship), an organization founded by Clark Professor John Dobson to help urban farmers enhance their business potential.

It was my first trip to Colombia, and I immediately fell in love with the country, which is energetic and emotional, and as beautiful as it is gritty.

In the song “Try Anything,” the Colombian singer Shakira has a line that says, “I wanna try everything / I wanna try even though I could fail.”

Shakira may not have been referring to urban farmers becoming better businesspeople, but she certainly got it right when it comes to entrepreneurship.

Starting a business isn’t easy. It takes perseverance and belief. Knowledge and resources help, but not everyone has that luxury. The farmers in Colombia came to our DYME sessions determined to learn new ways to grow their businesses. They were highly engaged and asked great questions; they enjoyed the experience of learning practical tips to enhance their businesses and lives.

I had the unique opportunity to teach my Marketing to You course in Spanish for the first time (it took a few months of intense classes with some local Spanish teachers to get ready). My confidence grew throughout my time in Colombia, which is important, considering that my focus was to instill confidence in the farmers to pitch their products! We equip them with skills, knowledge, and support—they take it from there.

It was a wonderful experience, and I can’t wait to return next year. I’m thankful to John for the invite and to all the remarkable Colombian entrepreneurs for their hospitality, attention, and desire to learn. I was honored to center the theme of my presentation around the importance of food to a country’s sense of pride and identity.

And it made perfect sense that we were paid by the farmers/entrepreneurs with an amazing bowl of homemade soup.

La comida es vida. Food is life.