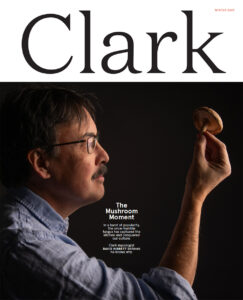

The once-humble fungus is capturing the kitchen and conquering our culture—and Clark mycologist David Hibbett is all in.

It’s the answer to a question that Professor David Hibbett likely thought he’d never be asked. But during the Q&A session hosted and filmed by WIRED magazine inside a Manhattan studio, the mycologist took it in stride, reassuring the world that the parasitic fungus that infects and kills other organisms does not, in fact, create an army of living-dead insects.

Sitting in front of a white backdrop and behind a tabletop bearing varieties of mushrooms, Hibbett fielded a series of fungi-related queries pulled from Twitter (now known as X). He identified the world’s largest known fungus (the 35-foot-long Phellinus ellipsoidius that is found in China), described his personal choice for the all-time creepiest mushroom (the appropriately named Bleeding Tooth Mushroom [Hydnellum peckii], which secretes blood-red droplets), and cleared up any confusion about whether there is such a thing as a carnivorous mushroom (indeed there is).

He also championed fungi as potential allies in the fight against environmental pollutants; revealed the hidden ways in which mushrooms communicate with each other; and extolled the joys of foraging.

The subject matter may have seemed humble, but the response to the video was not. Since it was posted on May 2, 2023, the WIRED piece has earned more than a million views and over 2,600 comments, many of them urging Hibbett to start his own mushroom-themed YouTube channel. “Everybody should be obsessed with mushrooms,” Hibbett gently noted at the conclusion of the video.

Some days, it seems everybody is. The Clark scientist has found himself part of a cultural phenomenon centered on the public’s fascination with all things fungal—expressed in everything from pillow designs to the postapocalyptic miniseries The Last of Us. Foraging groups are sprouting across the globe, luring thousands into the forests. Fungi were even the subject of a bestseller, Entangled Life, which earned the author, mycologist Merlin Sheldrake, the kind of exhaustive New York Times profile normally reserved for film stars and presidents.

Mushrooms—in just about every way possible—are having their moment. And David Hibbett is always ready to share his obsession.

Last summer, Hibbett and several of his students climbed into a canoe and set up the Ipswich River in search of one specific mushroom, carefully scanning the water’s surface as their paddles cut through the water.

He was looking to learn more about the semiaquatic Lentinus tigrinus, also called the Tiger Sawgill, a wood-decaying fungus that grows on trees such as willows, elms, and maples. Hibbett and his students made at least six trips to the river during the spring and summer, working in collaboration with fellow Clark professor Javier Tabima, a mycologist and evolutionary biologist who specializes in genomics and computational biology.

Lentinus tigrinus “fruit,” or blossom, on logs protruding from the river. During a rainy season, like summer 2023, they often end up underwater.

“I don’t think mushrooms are going to save the world. I think people are going to save the world, and mushrooms are the resources that will help us in this pursuit.”

Not a problem. Lentinus tigrinus has adapted to grow into two forms that allow it to thrive as water levels rise and recede. One form has gills that release spores into the air, typical of mushrooms. The other has gills covered by a layer of tissue, trapping the spores inside the fruiting body, which is unusual because “the only function of a mushroom is to release spores,” Hibbett says. He and Tabima want to understand the genetic mechanism behind the two forms.

“We want to know how natural selection is working on those genes. There’s something called ‘balancing selection,’ a model of natural selection that promotes the occurrence of two different forms in a population,” Hibbett says. “We believe there may be some balancing selection going on here.”

The Ipswich River trip is one of countless forays for Hibbett, who has conducted research all over the world. He’s authored nine articles in the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS)—and in nearly 200 other publications, including Science and Nature — that explore the evolution and ecology of fungi. He was deeply involved in the Open Tree of Life, a visionary project to create an accessible resource that would present the evolutionary relationships of all living organisms in one place, an effort that dates to Charles Darwin.

Hibbett’s likeness is so synonymous with mushrooms—Google “mycologist,” and at the top of the page you’ll find an image of Hibbett foraging in the woods—that it’s difficult to imagine him specializing in any other area of science. But that almost happened.

He describes his journey to mycology as “backward, serendipitous, and unplanned.” The Massachusetts native studied botany as an undergraduate at UMass Amherst, but thought mushrooms were “cool” and took a mycology course. He later spent a summer in a forest fungal ecology class at the University of Michigan Biological Field Station.

While pursuing his doctorate in botany at Duke University, pragmatism steered Hibbett into mycology when he realized fungi would make for an intriguing research subject. And besides, this was not a crowded field. He sensed a wide-open opportunity—and seized it.

Mushroom fandom is an ecosystem of its own.

The North American Mycological Association includes more than 90 affiliated mycological societies in the United States, Canada, and Mexico. Hibbett is on the executive committee of the Boston Mycological Club, which was founded in 1895 and has upward of 800 members. Clark has a new mycology club, attracting students from across disciplines.

“On mushroom walks you meet people in camo, people in tie-dye, and people in Oxford shirts,” Hibbett says. “These public forays have been attracting too many people, which is a good problem to have. Older club members who remember it being a little elite and obscure are having a hard time adjusting to the new reality; younger club members are really interested in getting more people of color involved. It’s an interesting dynamic.”

Hibbett has researched in Japan, China, and Malaysia and has collaborated with scientists from around the globe. One Jurassic Park-like encounter occurred at the American Museum of Natural History, where he worked with a 94-million-year-old specimen of a fossil mushroom trapped in amber.

Among Hibbett’s favorite foraging trips was a 1992 visit to Papua New Guinea, where he collected in lowland rainforests and found a relative of shiitake mushrooms called Lentinula lateritia. Last summer, he collaborated with a group of international researchers to investigate the genomics of shiitake mushrooms and discovered that the shiitake species boasts a vast genetic diversity.

“Mushrooms are a window to a secret world because they are so fantastic.”

The allure of mushrooms has a downside, Hibbett says. The nutritional supplement movement has issued significant claims about the benefits of mushrooms—that Lion’s Mane can boost cognitive health, for example. Hibbett advises taking a magnifying glass to the fine print, where one will discover that many health claims have not been tested by the FDA. The assertions are typically based on studies using cultured cells or mouse-model systems, vastly different from human trials and the arduous drug-approval process, he says.

“A lot of money is being made off cheap ingredients, and I have a problem with that,” he says. “People come to me all the time asking, ‘Is this mushroom medicinal?’ I don’t want to be associated with that, because that’s not my business.”

However, fungi do produce a myriad of potent secondary metabolites—small molecules that humans use in drugs such as penicillin, cyclosporine, and fungicides. They also make powerful physiologically active chemicals. “Magic mushrooms” were used for religious and healing rituals centuries ago in Mesoamerica, for recreation during the hippie counterculture of the 1960s and 70s, and more recently as a treatment for depression. A handful of communities across the country, including at least six in Massachusetts, are beginning to decriminalize psilocybin, a naturally occurring hallucinogenic that can be used therapeutically.

Mushrooms have become such a white-hot object of public fascination that Hibbett is concerned about the wider ramifications if people’s interest wanes.

“I’m worried that overhyping and overselling may cause people to turn away and not put in the time, energy, and money needed to develop the technologies for drug-discovery work related to mushrooms.”

Fungal biology is steeped in the history of Clark sciences. Hibbett arrived at the University in 1999, hired for the position previously held by eminent lichen specialist Vernon Ahmadjian at a time when the department chair was Tom Leonard, a fungal geneticist. Today, Hibbett is one of the University’s most cited researchers, with 33,212 citations on Google Scholar. In 2020, Tabima joined the faculty, giving Clark two mycologists, a rarity for a small research institution.

Tabima approaches biology from a unique perspective shaped by his wanderings in the mountains of his native Colombia, where he was mesmerized by the complexity and beauty of the ecosystem—towering monkey-filled trees, birds swooping across the sky, insects skittering at his feet. Last year, he became the first researcher to discover in Massachusetts a specimen of the Basidiobolus microfungus that typically lives in the guts of amphibians.

“People say that plants are the most important organisms on the face of the earth—but fungi are,” Tabima insists. “How do plants adapt to land? Ninety percent of plant species are associated with fungi that allow the plants to grab nutrients from the ground. What helps ruminant organisms process all the grass they eat? Fungi. What has led to the evolution of human conservation, food preservation, and products like beer? Fungi,” he says, adding with a grin, “which have inspired a bunch of hipsters to start craft breweries.”

As mycologists with vastly different research specialties, Hibbett and Tabima bring a distinct yin and yang to the Lasry Center for Bioscience. Hibbett investigates the fungi visible to the naked eye; Tabima’s subjects are microscopic.

The dichotomy extends to their personalities. Hibbett is witty and wry; Tabima is cheeky and irreverent. Hibbett wears neutral-tone button-down shirts; Tabima sports rock band T-shirts.

They complement one another beautifully, which led to the Ipswich River search for Lentinus tigrinus, a project melding Hibbett’s mycological expertise with Tabima’s genomics and population genetics knowledge.

“As a collaborator, David is incredible,” says Tabima of his colleague and mentor. “He knows how to get people involved; he knows how to get grants. He’s been leading international and national efforts on fungal diversity.

“He’s such a good scientist.”

For some, the aesthetic of a mushroom is nearly perfect. Home décor, from pillows to vases, is routinely manufactured in mushroom shapes, embellished with bold colors and funky patterns. For sophisticated foodies, mushrooms are a source of culinary creativity—in 2022, The New York Times called mushrooms the “ingredient of the year.” As the world emerged from pandemic shutdowns, mushrooms came to symbolize a reconnection to nature, with foraging excursions almost a celebratory escape from isolation and political and social tensions.

In the popular hbo miniseries The Last of Us, they also became the boogie man. The television adaptation of a 2013 PlayStation video game featured a cordyceps fungus that infects humans, transforming them into zombies.

“As a science nerd, I take issue with some of the show’s representation of the actual fungi, but that’s trivial,” Hibbett laughs. “I love the show and think it does what science fiction is supposed to do. It extrapolates, but from a reasonable place.”

But could the postapocalyptic narrative be reversed? Could fungi, in fact, be the hero?

Can mushrooms save the world?

Research supports the idea that mushrooms can decelerate environmental changes, Hibbett says. Mulch and wood piles inoculated with mushrooms are shown to slow forest fires, and mushrooms can be an asset for industrial purposes, like biofuel production. But these technologies require extensive research.

“It’s well-intentioned and based on real biology,” Hibbett says, “but is it effective? It’s certainly not cost-neutral because growing those fungi requires energy.”

Hibbett believes in a different antidote.

“I don’t think mushrooms are going to save the world,” he says. “I think people are going to save the world, and mushrooms are the resources that will help us in this pursuit.”

Perhaps above all, regardless of whether it’s portrayed as hero or villain, the modest mushroom will continue to be a source of mystery and wonder.

“Mushrooms are a window to a secret world because they are so fantastic,” Hibbett marvels. “They come in all these strange forms and magically appear, growing up from the ground or out of wood. They’re odd and beautiful things.

“They’re otherworldly.”

PHOTOGRAPHS BY STEVEN KING