SYLLABUS: CLARK IN THE CLASSROOM

The grass is not always greener

Students in an advanced biology class had the ultimate test for their final class project: present a proposal to create three mini ecological habitats on Clark’s campus. Their audience was faculty and campus leaders, including President David Fithian ’87.

The Nov. 27 presentation was the culmination of Biology Professor Elizabeth Bone’s Ecological Restoration class, where students researched how former farmlands and overlooked urban spaces could be turned into thriving, climate change-resistant ecosystems that support a diversity of wildlife. The class was a Problems of Practice course, which allows students to gain skills and experience working with organizations outside the classroom.

“I liked how practical the class was, giving you something you could use instead of sitting in a classroom and taking notes,” said Annemaire Walsh ’25, an environmental science major.

To observe successful restoration efforts under way, the students visited two former cranberry bogs just north of Cape Cod — the 128-acre Foothills Preserve and 60-acre Eel River Headwaters Restoration Project — managed by the Town of Plymouth and supported by Living Observatory, a nonprofit organization of scientists, artists, and wetland restoration practitioners.

“They were working cranberry bogs, but when the economics of cranberry bog farming changed, they were retired, and now there’s a push to restore them,” Bone said. “The idea is to bring the system back to something more natural.”

The students took samples of ant species (the more diverse the ants, the healthier the ecosystem) and later presented a research poster, “Ants on a Bog?! A Comparison of Biodiversity on Restored Cranberry Bogs at Different Stages of Restoration in Plymouth, Massachusetts,” for ClarkFEST, the University-wide student research event on Oct. 25.

The class — which included upper-level students majoring in biology or environmental science — also took field trips to conservation sites closer to Clark — Wachusett Meadows, a former farmstead near Princeton; Elm Hill Wildlife Sanctuary in North Brookfield; and Quaboag Wildlife Management Area near Brookfield.

Yet, Bone pointed out, “conservation and restoration don’t only need to happen on rural sites. They can also happen on some of these small spaces on campus to create urban micro habitats and convert them into self-sufficient ecosystems.”

“I liked how practical the class was, giving you something you could use instead of sitting in a classroom and taking notes.”

— Annemaire Walsh ’25

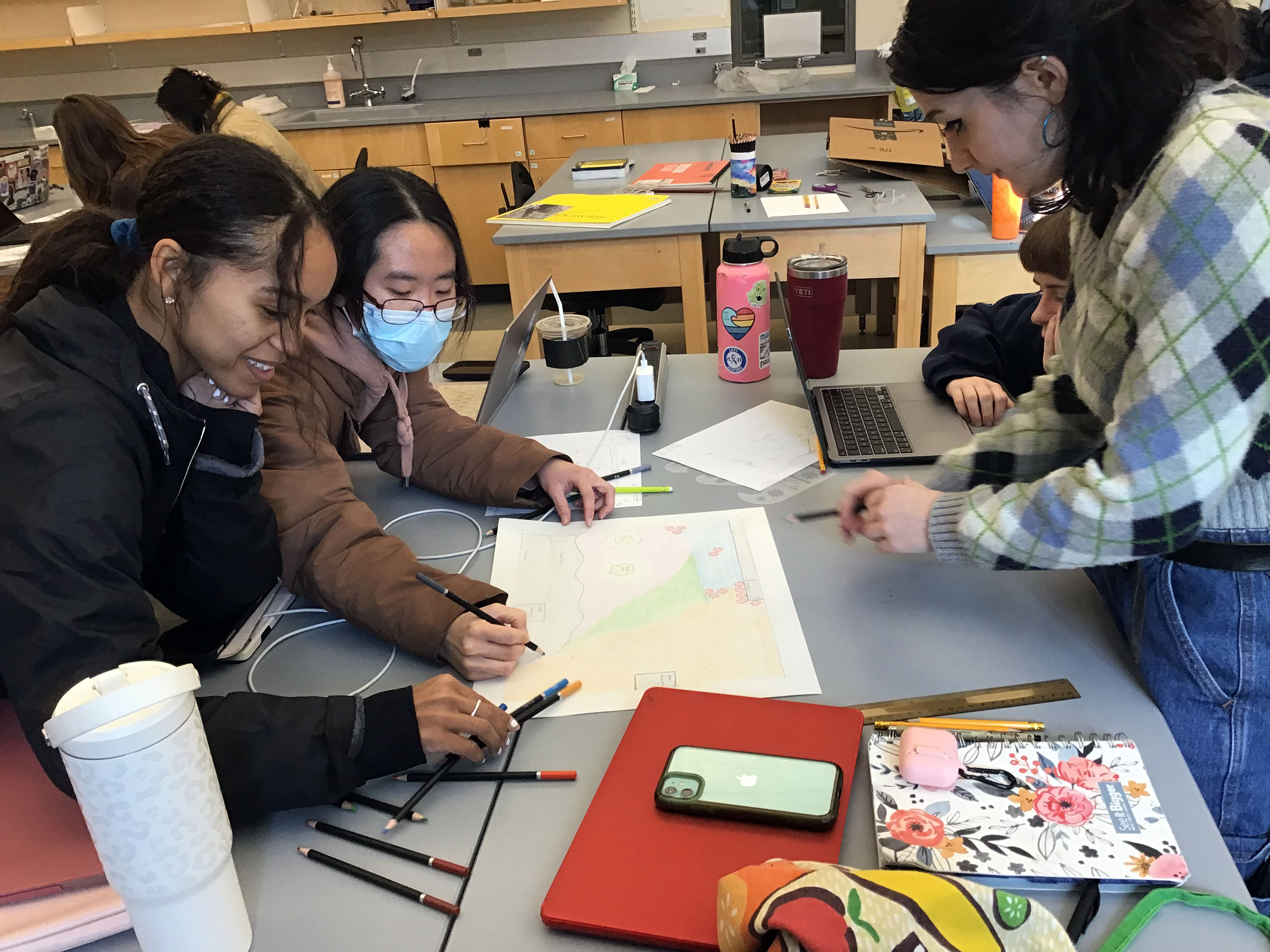

During one class, the students spread out through campus to look for pockets of land that might benefit from the restoration practices they had observed.

They identified three areas: abutting the Kneller Center near Goddard Library; between Wright Hall and Little Center; and near the University Police entrance at the basement level of Bullock Hall. These spaces are prone to rainwater runoff and salting due to ice buildup, making them less habitable for a diverse variety of plants and insects and less inviting to people. Some of the overlooking buildings’ basement and first-floor rooms also might benefit from plantings that would provide more privacy, the students suggested.

The students researched the amount of rainfall and daily sunlight the areas receive to suggest shrubs, ferns, wildflowers, and other plants — such as woodland phlox, New England asters, swamp milkweed, lupines, and lowbush blueberry — that might thrive and, as an added benefit, attract birds and insects, including pollinators. They designed and mapped out plantings and pathways, developed cost analyses, and created site management plans.

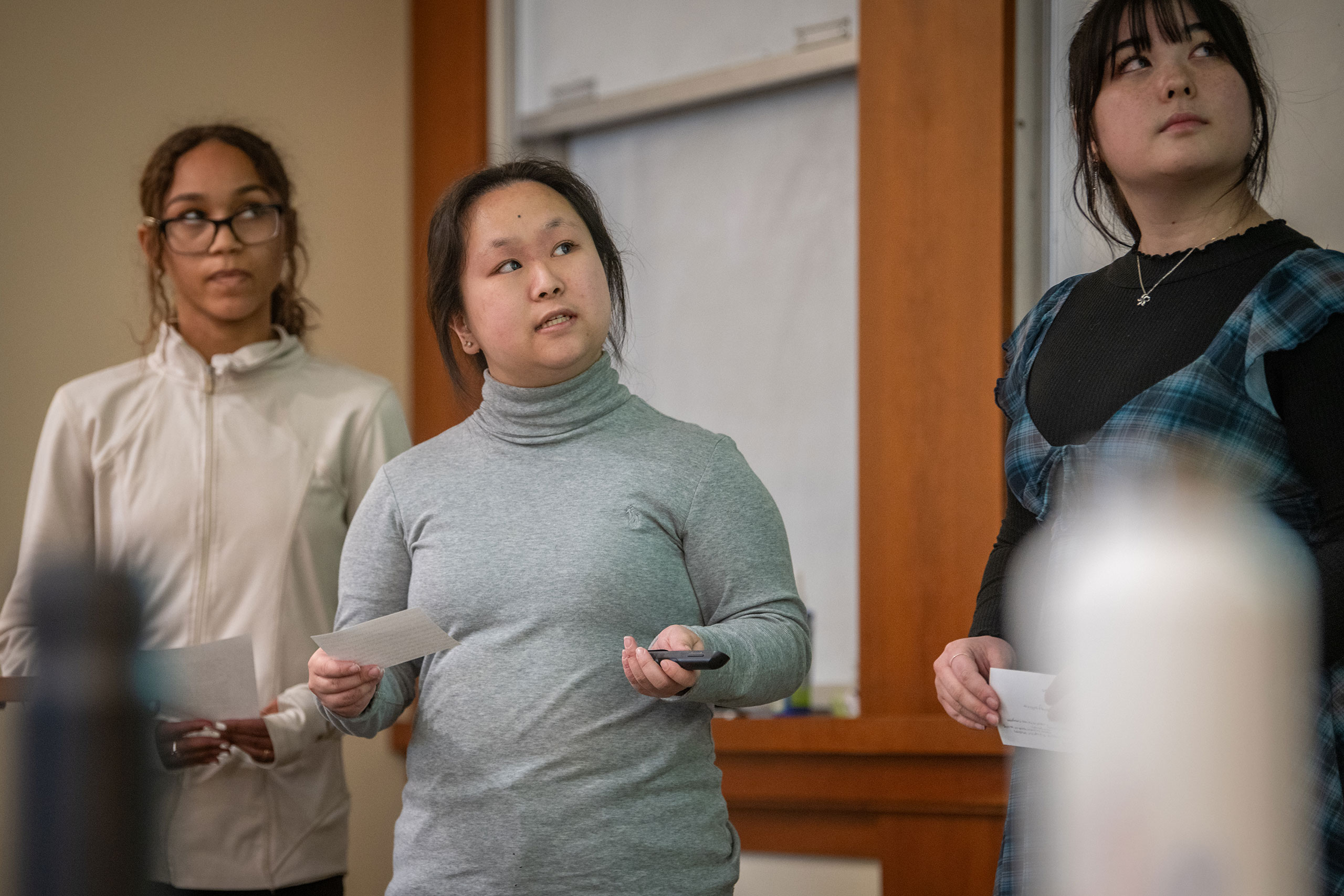

“One of the main goals of the project is to increase the value of some of Clark’s green spaces by increasing biodiversity — adding species that benefit wildlife, address landscape concerns, increase the aesthetic value, add student research project opportunities, and increase climate change resiliency,” Yuna Parrish ’24 told campus leaders.

The students also seek “to create a simple and universally applicable protocol for urban restoration design that can be repeated at other locations,” including other campuses in Worcester, she added.

The project “aligns with Clark’s mission of educating students to be imaginative and contributing citizens,” Janet Lim ’24 said, and could provide opportunities “where future students could identify ways to improve the microhabitats or come up with creative solutions to potential problems.”

Students later fielded questions and comments from faculty and administrators, including whether the campus community would accept less mowing, raking, or leaf blowing in areas that might be left more to the wild. The students acknowledged the need for more education about their efforts, and one faculty member suggested that educational signage could help.

For now, the students’ proposal will be studied by Facilities Management and David Chearo, vice president for planning and chief of staff. Bone hopes to teach the class annually, encouraging students to draw upon previous cohorts’ research and to develop new projects.

“I want to thank you for all this work and effort and congratulate you on a job really well done,” President Fithian said. “This is a topic near and dear to my heart. As a former Clark student who was here at a very different time on a very different campus, I can say that the aesthetics of campus really add to the experience of being here as a student.”

Image at top of story, from front: Ella Incantalupo ’25, Yuna Parrish ’24, Emily Wells ’24, Isabelle Appiah ’24, and Sam Norton ’24 arrive at Plymouth’s Foothills Preserve on a rainy September weekend. Because ants do not emerge in the rain, the 12 students in the class only were able to collect a few as part of their study of the ecosystem. They suggested to Biology Professor Elizabeth Bone that future cohorts “weather-proof” their ecological research by focusing on plants.

Photo: Steven King, director of photography / university photographer