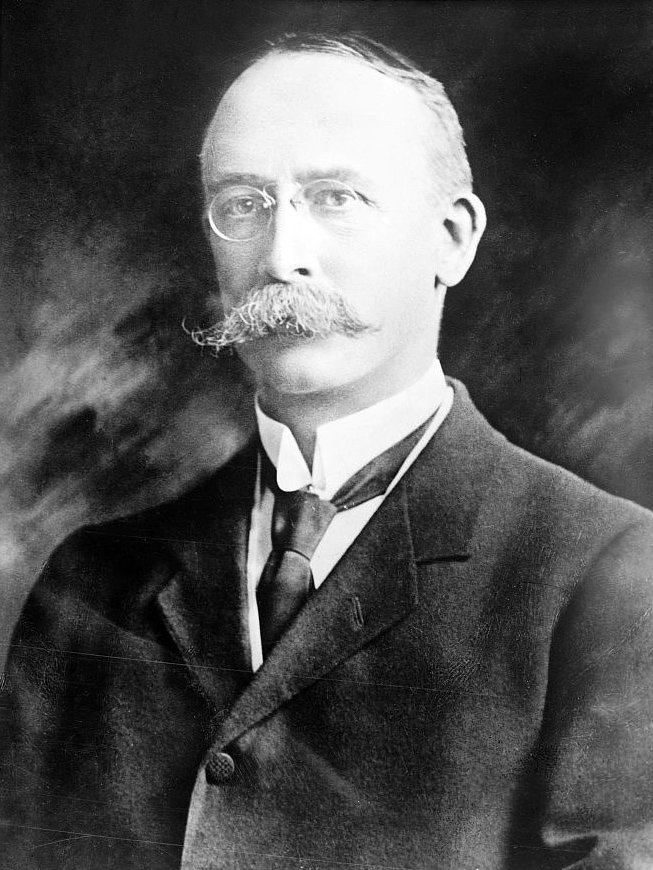

‘Wherever science is discussed, his name was known.’

Born in Brookline, Massachusetts, Arthur Gordon Webster excelled in mathematics and physics at Harvard College, where he graduated at the head of his class in 1885. After a year as an instructor at Harvard, he continued his studies at the University of Berlin. Webster also briefly attended the universities of Paris and Stockholm before receiving his Ph.D. from Berlin in 1890. After completing his European studies, Webster began a lifelong affiliation with Clark University. He spent his first two years there as a docent in physics, working under Albert A. Michelson. Following Michelson’s move in 1892 to the University of Chicago, Clark administrators promoted Webster to assistant professor and placed him in charge of the physics department and laboratory. He held the rank of full professor from 1900 until his death.

The following excerpts are taken from “Clark University 1887–1987, A Narrative History,” by William A. Koelsch (Clark University Press, 1987).

A brilliant mathematical physicist in a day when theoretical physicists were exceedingly rare in America, he had studied in Paris, Stockholm, and Berlin and was said to be the great Helmholtz’s favorite American student. Webster was fluent in German, French and Swedish, had a good working knowledge of Spanish and Italian, and possessed some competence in Russian and modern Greek. Fresh from his Berlin Ph.D., he had arrived in Worcester in the fall of 1890 to take up his post as docent in Michelson’s department. As he stepped off the horse-car, Webster was unpleasantly shocked by the contrast between the grand university facilities he had known abroad and the simple picket fence, the overgrown lawn, “and the now familiar architecture of the main building which … did not arouse my enthusiasm,” he recalled years later. Given charge of the department in 1892, Webster remained the sole representative of physics at the graduate level until 1920.

Webster was a good experimentalist and made significant contributions to the physics of sound. He designed an ingenious portable phonometer for making absolute measurements of the intensity of sound, developed sound-detecting devices for ships in the days before radar, and developed the concept of acoustic impedance. He also did important work in gyroscopic motion and developed a new series of measurements for physical constants. Webster’s experimental research on electrical oscillations received international recognition in Paris in 1895 with the award of the Elihu Thomson prize of five thousand francs.

Webster was the principal founder, first secretary, and third president of the American Physical Society. After his death, a writer in The New York Times commented that “wherever science is discussed, his name was known.” Webster was extraordinarily competent in the literature and had laboratory experience with a wide range of probes in classical physics. He was also one of the first American physicists to lecture on quantum theory, electron theory, and relativity. But he could never fully accept the implications of the revolutionary advances in his own day coming out of work with x-rays, atomic structure and the theory of relativity which were replacing the certainties of classical physics with a new world order which Webster found increasingly troublesome, intellectually and personally.

Webster was also a vivid and forceful lecturer and wrote classic texts on the theory of electricity and magnetism and on theoretical mechanics, one of which begins with the words “It is the lofty aim of mathematical or theoretical physics to describe the universe in the most accurate manner.” His “Theory of Electricity” (1897) was the first major treatise in this area to be written by an American, and one leading physicist said of his discussion of electromagnetic theory that its elegance and clarity had “never been equaled in English or in any other language.” But Barnes wrote of Webster’s teaching that “He has instructed some, and appalled more, by his facility in filling six blackboards with forbidding and unintelligible mathematical symbols during a single lecture in the midst of a blinding barrage of chalk dust.”

Webster turned out nearly thirty physics Ph.D.s, all of them thoroughly trained in classical experimental and theoretical physics. In 1911 two of the three students receiving doctorates in physics and mathematics were Solomon Lefschetz, later a distinguished Princeton mathematician, and Robert Hutchings Goddard, a Worcester-born graduate of Worcester Polytechnic Institute. Goddard returned to Clark after a year of post-doctoral research at Princeton to teach in the college, where Webster himself had launched the undergraduate physics program. Webster encouraged Goddard’s rocket research and stoutly defended its possibilities at a time when the notion of a rocket which would carry men to the moon was decried by scientist and journalist alike.

Webster later claimed to be the first American physicist to lecture on ballistics as part of his physics courses. Although he had been an outspoken pacifist before 1917, as soon as the United States entered the World War he virtually turned the physics laboratories into a ballistics institute, funded by the Naval Consulting Board and other agencies. Although Webster’s Institute was limited in scope by comparison with German efforts, out of it came a series of papers on the theory and practice of gunnery. Webster’s first assistant, Louis T. E. Thompson, became the Navy’s first civilian ballistician and two other institute associates, Goddard and Clarence Hickman, became pioneers in rocketry. At the end of the war the three formed a small industrial research laboratory, another concept somewhat in advance of its time, taking contracts for research in ballistics and in electrical components. But the war and its aftermath had also demonstrated that the scale of graduate work in physics at Clark was no longer viable, and in 1920 no new students registered in the physics program.

[In the early 1920s, Clark President Wallace Atwood planned a radical reorganization of the University.]

In May, 1923, Arthur Gordon Webster took his own life in his office in the physics laboratories. Increasingly eccentric in his later years and depressed both over his own work and the future of graduate programs at Clark, he feared (with good reason) that under the reorganization he would be dropped from the faculty in his sixtieth year with no resources on which to survive. In fact, Atwood had tried early in 1921 to get him to retire and, that having failed, to convert his professorship into a short-term research post with no future guarantees.