How much do we value healthy rivers and streams?

The economic benefit of water quality improvements depends on where those improvements occur. But which water quality changes do New England residents value the most, and where would they prefer these changes to occur across large river and stream networks? Robert J. Johnston, director of the George Perkins Marsh Institute and professor of economics, and a team of researchers developed a novel method for determining this information. The method is highlighted in “Spatial Dimensions of Water Quality Value in New England River Networks” published this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

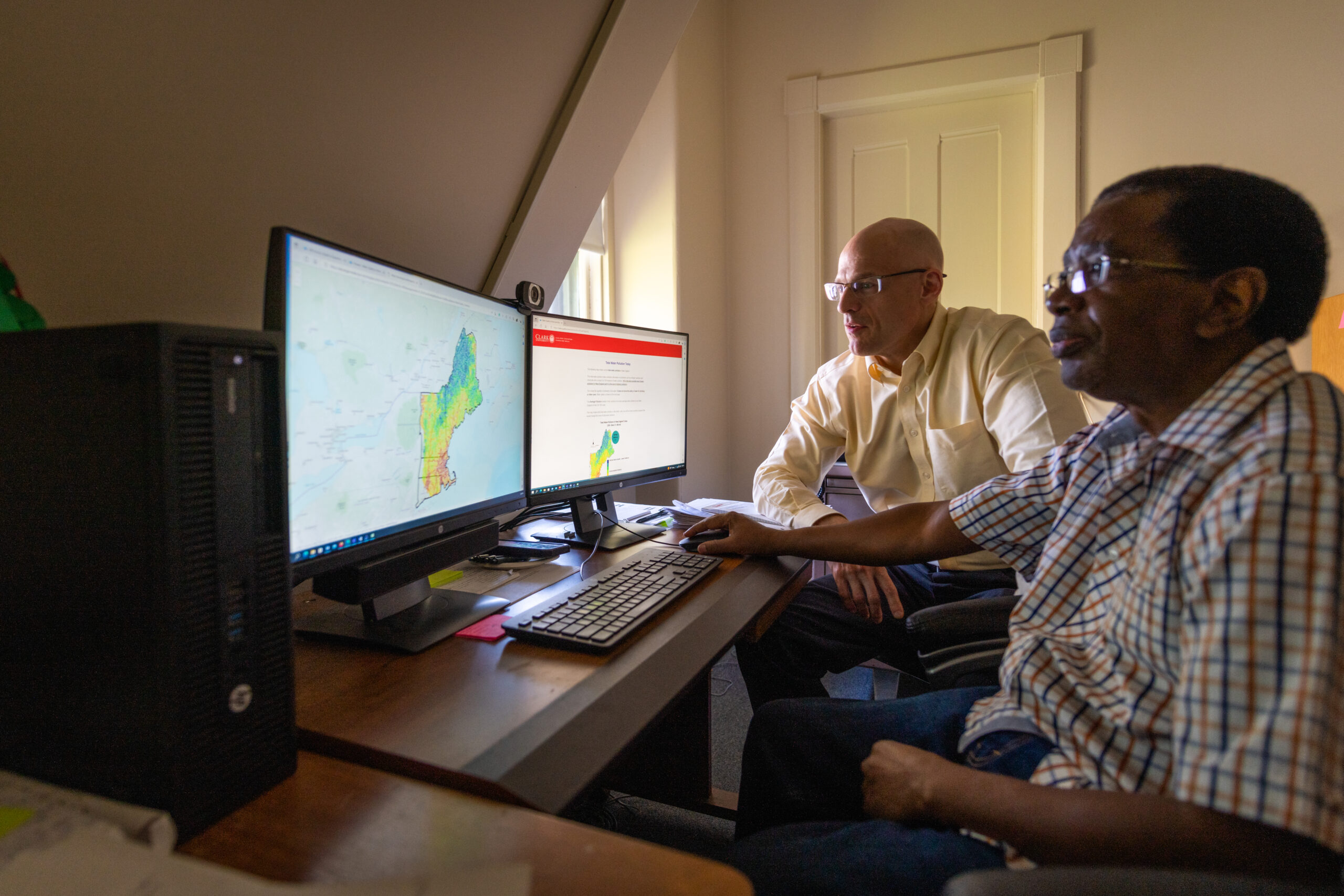

Johnston’s study was supported by a grant from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Science to Achieve Results (STAR) Program. His research team included faculty, scientists, and geographic information system (GIS) architects from Clark, Virginia Tech, the University of New Hampshire, and the consulting firm ICF International. Within the study, Johnston and his team developed a unique online survey interface that enabled people to actively explore future scenarios of water quality change using interactive maps. These maps showed alternative scenarios for improving future water quality, for instance, to support aquatic life or human uses like swimming and fishing in different areas across New England. Survey participants across the region were then asked whether they would vote for or against these scenarios in a hypothetically binding public referendum, at a given annual cost to their household.

“We found that allowing people to examine online maps of water quality change as part of these surveys tells us a lot about what people value and where,” says Johnston, the lead author of the paper. “When exploring these water quality changes on their own — for example, panning and zooming on the maps — people naturally spent more time looking at the areas they value most. Understanding these locations allows us to better predict what type of water quality changes people value and what type of programs they support. This is the first time that map-tracking data of this type has been used to help us understand the value of water quality to the public.

“When people think about what kind of water-quality policies they support, they seem to be thinking in a spatial and sophisticated way,” Johnston says. “If water quality improves a lot in areas that people examine on a map, they’re more likely to vote ‘yes’ for that policy. And if water quality doesn’t change in those high-attention areas, they’re less likely to support it. We can use this information to predict what they would be willing to pay for water quality improvements in rivers and streams across New England.”

The survey also indicated that people care more about improving New England’s low-quality rivers than further improving the region’s high-quality rivers. “People not only care about where water quality improvements are on the map,” says Johnston, “but what types of improvements are made in those areas.”

A total of 1,698 people completed the survey across New England, and of those, 1,239 voluntarily explored the digital water quality maps when given the opportunity. The researchers found that people tend to hold high values for water quality improvements that occur close to their homes, as expected. But many people explored other areas on the map that were nowhere near their home — and improvements in these areas were also linked to particularly high values.

As explained by Johnston, “survey respondents often used the interactive maps to explore water quality conditions in densely populated areas such as southeastern New Hampshire, the greater Boston metropolitan area, and much of Rhode Island. This makes sense, because many of the respondents live in those general areas.” However, many respondents explored water quality improvements in areas that are less densely populated and far from their homes, such as some areas in Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine. “These could be locations where people recreate, where they own a second home, or areas they care about for other reasons,” Johnston notes. “People value water quality for many different reasons, and not only close to their primary homes.”

One of the main goals of the project was to improve the methods used to measure the economic value of water quality improvements within benefit-cost analyses conducted by federal and state agencies, for example within regulatory rulemaking under the US Clean Water Act. Johnston says this mapping methodology could be helpful when evaluating future policies and programs to improve water quality across the US.

“The extent to which people value water quality improvements depends on where these changes occur — it’s not one size fits all,” Johnston says. “But we don’t always know in advance what types of improvements people value and where. Each person might value water quality improvements in different areas — and that matters when we are trying to predict benefits. This approach can help economists and decision-makers better understand these spatial dimensions.”

Learn more details about this research project.