In Vienna seminar, students explore ‘one of the most famous moments in cultural history’

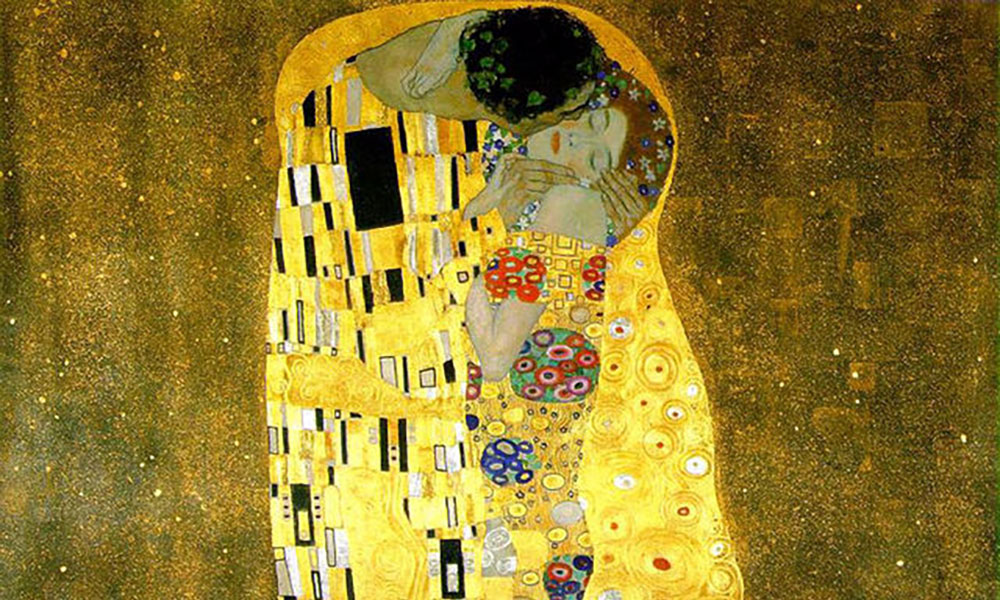

A section of ”The Kiss” by Secessionist painter Gustav Klimt

In her last semester as an undergraduate student at Clark University, Kaya Middleton-Grant ’23 was looking for an engaging course to fulfill a requirement for her B.A. in media, culture, and the arts. So she signed up for a small, interdisciplinary, advanced seminar on “Vienna, 1890-1938: Capital of Tradition, Innovation, Promise, and Peril.”

“I have always been interested in trying new things and engaging with academic topics that are unfamiliar to me to broaden my connection to the world, more specifically, different art and cultural mediums,” explains Middleton-Grant, who is also majoring in Spanish. “I thought it would be a good opportunity to dive into an area that was new to me.”

She found herself immersed in a world she had never explored: fin-de-siècle Vienna, where art, music, culture, science, and philosophy flourished, rivaling Paris as the center of European culture at the turn of the century.

“The period around 1900 in Vienna has become one of the most famous moments in cultural history,” says Benjamin Korstvedt, professor of music, who launched the course this spring with Frances Tanzer, Rose Professor of Holocaust Studies and Modern Jewish History and Culture and assistant professor of history.

Vienna produced composers like Gustav Mahler and Arnold Schoenberg; psychologist Sigmund Freud (whose statue sits at the center of Clark’s campus, to mark his only U.S. lectures here); and secessionist painter Gustav Klimt. Historians have resurrected the stories of women who played a role in the bustling cultural and economic hub. Fanny Harlfinger-Zakucka participated in the radical Vienna Secession art movement alongside Klimt, and ceramic artist Vally Wieselthier produced now-celebrated Art Deco pieces.

Starting in the 1980s, historians inspired by Carl E. Schorske, who wrote the Pulitzer Prize-winning book “Fin-de-Siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture,” began to romanticize this age of Vienna, treating it “as a sort of twilight, shadowed by rising antisemitism and the looming threat of fascism that was to come full force in the 1930s,” Korstvedt says. “This view is far from baseless, but it overlooks a great deal that was going on — artistically, socially, politically, intellectually — in Vienna during this era and especially in the two decades between World War One and the Nazi takeover in 1938.”

Funded by a Clark Innovation Grant, the course has included complementary events on campus, providing students and the Clark community with a chance to dive deeper into Vienna’s rich and complex cultural landscape. The seminar will culminate in a daylong symposium on Friday, April 21 that will draw expert speakers from across the country to Clark, ending with a public concert of Viennese song that evening. Earlier, the course featured a public screening of Hans Karl Breslauer’s long-lost 1924 silent film, “The City Without Jews,” accompanied by live music. One of the foremost authorities on the film, Lisa Silverman, associate professor of history at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, will speak at the conference this week.

In the years before Hitler’s 1938 annexation of Austria — the Anschluss — Vienna had a thriving Jewish population. The class studied Maximilian Hugo Bettauer’s 1922 satirical novella, “The City Without Jews,” which preceded the film. Students heard from Silverman, a guest lecturer for the class, before the film screening.

The fictional story, in which the National Assembly passes a law that forces the Jewish population to leave the city, now seems eerily prescient because contemporary audiences watch the film with the knowledge of the Holocaust, Tanzer points out. Yet the film, released 16 years before the Anschluss, it was a mixture of light-hearted entertainment and melodrama meant to entertain audiences rather than to encourage them to consider a possible looming threat.

“Though the film portrays antisemitism, it was hardly a premonition,” Tanzer explains. “Rather, it is a cultural product that grew out of a world where Jews really were present and where Jewish stereotypes provided a dominant way for making value judgements on urban culture. Meanwhile, our moment is marked by the aftermath of the Holocaust by the realization of a profound Jewish absence in Vienna.”

She adds that “our class has endeavored to understand the ways that the meaning of cultural materials has shifted through the 20th century, particularly during and after the Holocaust.”

Throughout the seminar, students have recalled the similarities between the rising antisemitism and reactionary conservatism of interwar Europe and the right-wing politics that continue to target minorities and immigrants today.

“There are so many themes that our class has touched on that are so important for thinking about the contemporary world,” Tanzer says. “One of our major themes is the relationship between art and politics. What happens when artists are working in a more restrictive political climate? How is their work interpreted? What happens if they are forced to flee? These are some of the questions that come up in the class, and I think that they’re still questions we have today.”

Doctoral students in the Holocaust and Genocide Studies Program are taking the seminar, adding another level of expertise to classroom discussions.

“Fin-de-siècle Vienna has been portrayed as an outpouring of liberal culture and ideals, but that’s really not an accurate representation of what it was like,” says Nathan Lucky, a first-year doctoral student and Tanzer’s advisee. “Instead, conservative ideology and conservative intellectualism ruled the day for most of the interwar period, and that somewhat explains how these pan-Germanic and fascist ideas came about.”

Emily Steiger ’23, a media, culture, and the arts major and marketing minor, appreciates the wide range of critical and analytical readings for the class, and the team-teaching by Tanzer and Korstvedt, who bring in different areas of expertise that enrich class discussions.

“This class has given me the structure to know how to talk to people in an elevated setting,” Steiger says. “That’s one thing I like to explain when I’m in job interviews. My education has given me a well-rounded vocabulary, which is absolutely necessary for certain fields. At the end of the day, if you don’t know how to communicate with people, you’re lost.”