Harry Houdini spent much of his life escaping from chains and straitjackets, but the one thing he never tried to elude was a robust intellectual argument. And he nearly had a doozy at Clark University.

From Clark magazine, winter 2023On November 29, 1926, Clark University faculty and students, along with members of the public, gathered in the auditorium of the Main Building (now called Jonas Clark Hall) for the first in a series of lectures around a subject not covered in any of the University’s classrooms: spiritualism.

The lecture series, “The Case For and Against Psychical Research,” was funded through a bequest by Susan Clark, Jonas Clark’s widow, who in her will left $5,300 to Clark University to establish a special fund for psychical research. The conference was organized by Professor Carl Murchison, the chair of the Clark Psychology Department, who wrote in the preface to a 1927 collection of the event’s lectures and additional essays “that Clark University, in promoting this symposium, is by no means assuming the role of friend to psychical research and its various adherents. Clark University is assuming only the role of parliamentarian in the controversy.”

The idea for the 1926 symposium came to Murchison while eating lunch in Worcester’s Bancroft Hotel with Harvard University Professor William McDougall and a more well-known guest — MacDougall’s friend, magician Harry Houdini. “[We] began talking about spirit mediums, psychic phenomena, and other matters relating to psychical research,” Murchison wrote. “Professor McDougall and Mr. Houdini, though the best of friends, did not seem to be in entire agreement concerning certain matters that have become of wide social interest because of newspaper emphasis. Half-jokingly and half in earnest, I suggested that they and other representatives thrash out the entire matter in a public symposium to be held at Clark University.”

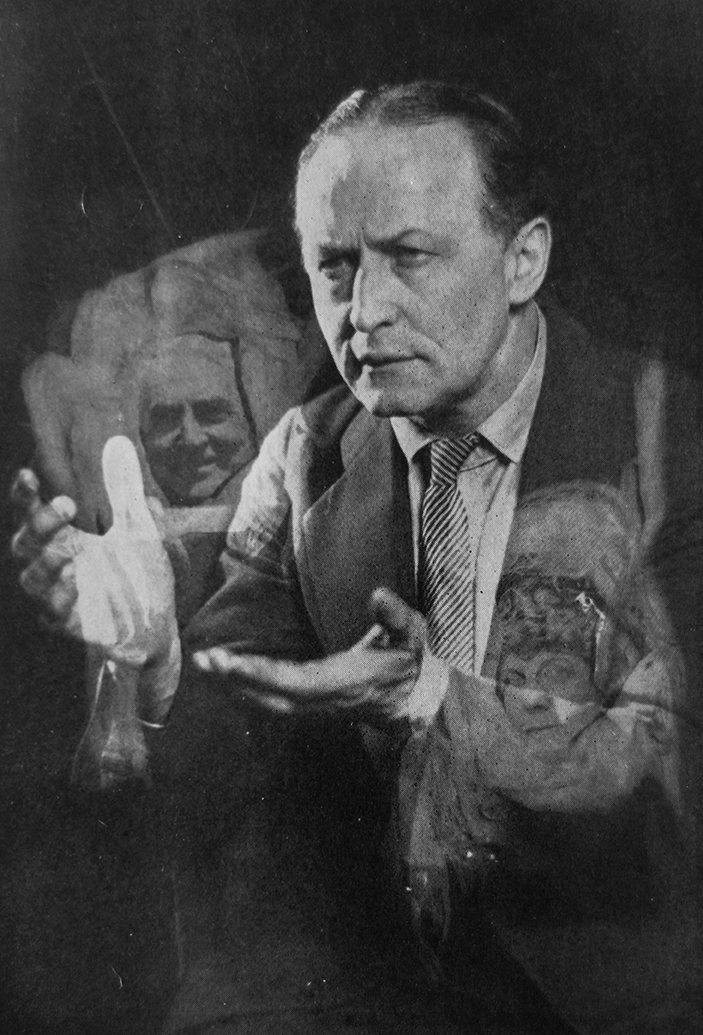

The series of eight lectures included arguments from ardent supporters of spiritualism as well as its fervent opponents. Houdini was among the latter, and for years had been publicly campaigning against spiritualism, debunking mediums and exposing their fraudulent acts. As an illusionist, he easily saw through the various tricks used to deceive believers. Houdini was slated to give the Clark series’ closing lecture, but he died of a ruptured appendix on Oct. 31, just a month before he was to visit campus.

Nevertheless, Murchison worked with Houdini’s widow to include several chapters from Houdini’s book “A Magician Among the Spiritualists” in the 1927 essay collection. “This book is only two years old, and Mrs. Houdini agrees that it still represents Mr. Houdini’s final convictions on the subject,” Murchison wrote.

Strongly disagreeing with his longtime friend Houdini was Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Houdini’s chapter actually includes many letters he exchanged with Conan Doyle). Best known as the creator of the fictional detective Sherlock Holmes, Conan Doyle contributed an essay for the Clark event titled “The Psychic Question as I See It,” which asserted his firm belief in spiritualism and predicted that it would “lift humanity to a higher plane.” Murchison read the essay to the November 29 audience.

Murchison insisted that he and his Psychology Department colleagues — though not convinced of the validity of psychical interpretations — guaranteed “fair play” throughout the symposium.

“If there is a spirit world,” he said, “we also, being human beings, are interested in learning about it.”