‘I realized it was time to talk.’

The Rose Library in the Strassler Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies is lined with volumes of remembrance — scholarly histories and personal testimonies that challenge us to confront some of the darkest chapters in the human narrative.

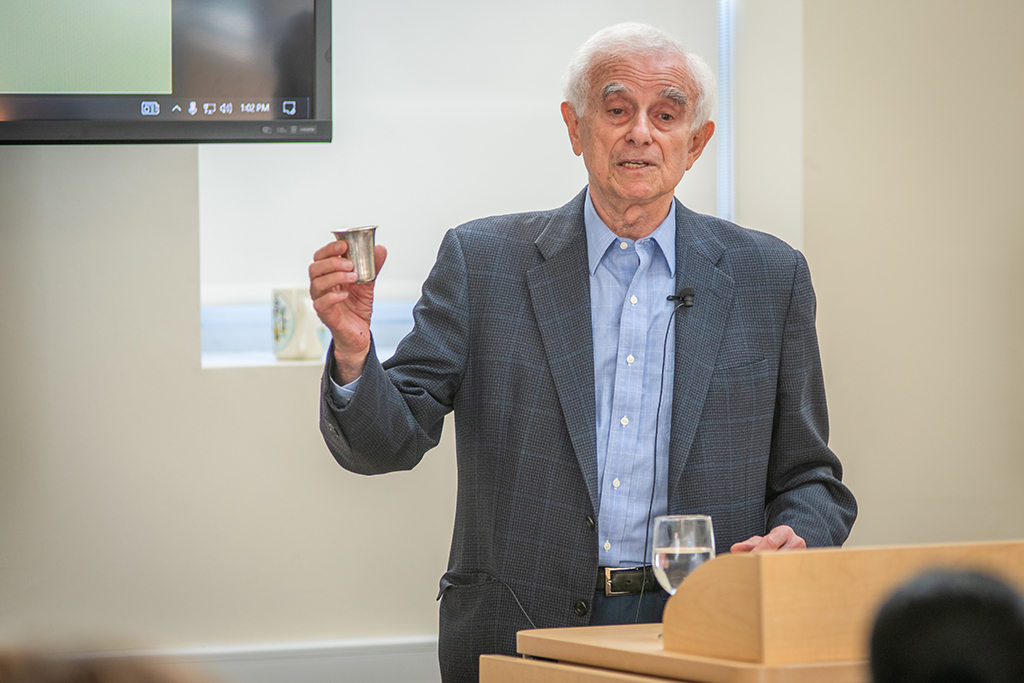

So it was particularly appropriate that on a November visit to Clark University, Fred Schoenfeld, 86, stood at a podium in the Rose Library, mere steps from these same books, to deliver his gripping account of surviving the Nazi regime as a young boy in Slovakia.

For the audience of invited guests, which included his son Steven ’84 and Steven’s family (his son Bruce ’87 is also a Clark alum), Schoenfeld recalled the days during the Second World War when the citizens in his town of Presov turned against their Jewish neighbors.

The enmity came in stages: Jewish business owners were ordered to divulge their finances; Jewish residents were forbidden to go to the movies and for their children to play in the playgrounds; friendly neighbors suddenly turned cold. Schoenfeld remembered his teacher directing him and a handful of fellow Jewish students to sit in the back of the classroom and demanding he keep his distance from the other children during recess. “Kids that you were friendly with last week now were calling you a filthy Jew,” he recalled. Anyone over the age of 9 was ordered to wear the Star of David on their shirt.

At one point during the presentation, Schoenfeld displayed a picture of himself as a boy with his grandfather, taken in April 1942. Six weeks later, his grandfather was put on a train and sent to Auschwitz. “It’s the last time I saw him,” he said.

Any time the trains pulled into town to transport people to the labor camps, the Jewish residents scattered, Schoenfeld recalled. Once, when police were looking for women to load into the cars, Fred’s father, Simcha ordered his son into bed where he feigned that he was sick. An officer arrived at the door, and the senior Schoenfeld convinced him that young Fred’s mother, Ilonka, needed to stay and care for her ailing son. “By a sheer miracle, he turned and left.”

By 1943, amid this atmosphere of hatred and betrayal, living in town became untenable. Fred and his parents hid in the attic of a warehouse for seven weeks, communicating in whispers to escape detection by the workers just a floor below. An employee of Simcha’s would smuggle in food and water beneath a long raincoat. To pass the time, Ilonka murmured stories about her childhood growing up on a farm — anything to keep her fidgety 7-year-old from accidentally revealing their hiding place. “One peep, and it was all over,” Schoenfeld said.

The family was able to emerge for a time, but when deportations continued, they were forced back to the attic for weeks more.

The Schoenfelds eventually escaped into the Tatra mountains in the autumn of 1944. Partisan fighters sometimes brought provisions; Fred tried to dull his hunger by eating snow. As battle conditions worsened, the families moved higher into the mountains, with about 40 people crowding into a hunting lodge.

The war was going badly for the Germans as American, Czech, and Russian troops closed in, but the fighting remained fierce and desperate. Schoenfeld remembers a night in January 1945 when a band of Russian and Czech troops arrived at the lodge to warn them of an approaching German force. Before heading off to fight, they reassured the families they would return to evacuate them.

“There were lots of Jews in the Czech army, and I will always remember hearing a soldier with a gun speaking Yiddish,” he told the Strassler audience. He also never forgot the kindness of one soldier who gave him a thick slice of bread. “I ate half and put the other half aside for a rainy day,” he recounted with a smile.

As promised, the soldiers returned to liberate the families amid the sounds of nearby explosions and firing rifles. “We were told, ‘When you hear a whistling sound, you have to hit the ground.’ The bullets were flying.” Processing in single file, the group passed the bloodied corpses of soldiers half-buried in the snow. They spent the night with the army, then were put onto a truck that transported the Schoenfelds to Fred’s hometown as the war wound down.

“Every day in the afternoon the trucks would pull in, bringing back survivors from the concentration camps, some of them still wearing their striped uniforms,” he said. “There were many happy reunions, but in many other cases there were no reunions.”

The Schoenfelds immigrated to the United States in 1948, settling in Pittsburgh when Fred was 14 years old, and two years later relocating to New York following Simcha’s death. In 1998, at the urging of his sons, Fred made a return trip to Europe to see his childhood home, but he was met with some suspicion by local residents who believed he only wanted to reclaim property his family had lost in the war. When he visited his grandfather’s hometown, he saw swastikas being whitewashed off the local synagogue. “Fifty years later, and nothing had changed,” he lamented.

For many years, Fred Schoenfeld didn’t speak much about his wartime experiences. But for the past five years he has been talking to middle and high school students in New York City about the series of events that beset his family and the Jewish people, and their lingering impact.

“Thinking it over, and especially in the last few years when I heard Holocaust deniers saying this never happened, I realized something important,” he said. “I realized it was time to talk.”