Clark Magazine

Nothing but Net

When Giannis Antetokounmpo fell to the hardwood, his face contorted in pain, the championship prospects of the Milwaukee Bucks seemed to topple with him.

It was Game 4 of last year’s Eastern Conference finals against the Atlanta Hawks. The Bucks’ towering center had leaped to defend a pass, then crumbled, clutching his left knee. As the medical staff sprinted to Giannis’ side, his teammates watched in stunned silence. Even the Hawks players appeared unsettled by the sight of the big man brought low.

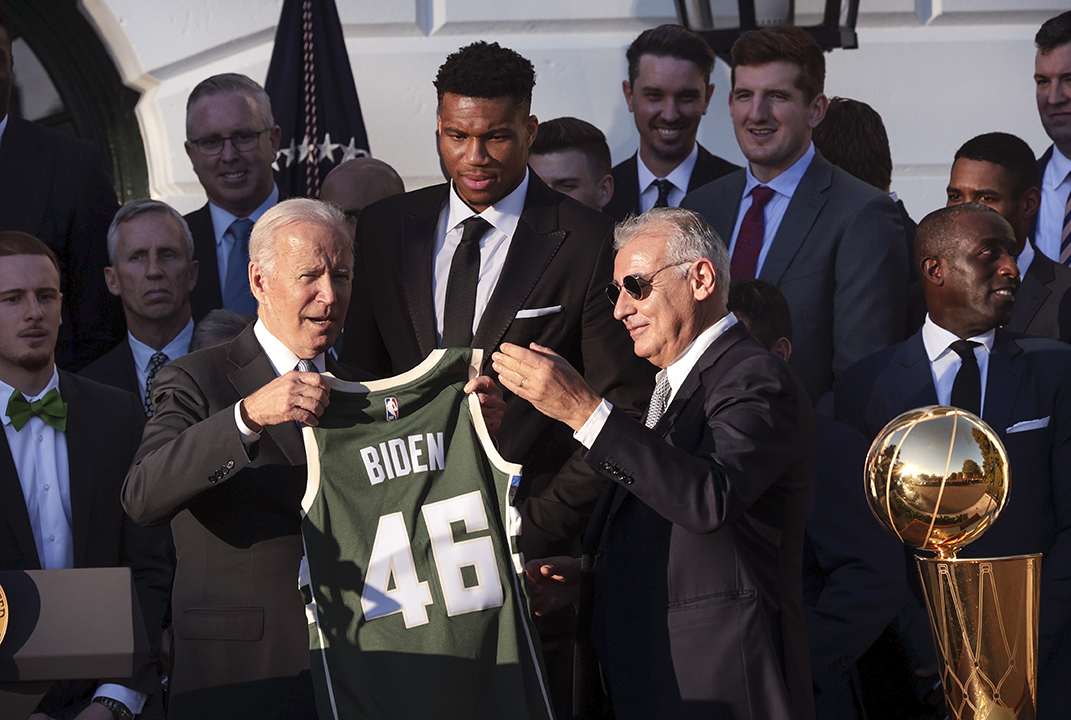

“It looked horrible from where I was sitting,” recalls Marc Lasry ’81, co-owner of the Bucks. “I just hoped that he was all right.”

Replays revealed that Giannis had landed awkwardly — the knee bent backward, as if mocking the limits of his anatomy. After he’d limped off the court with the assistance of two trainers, the Hawks played their way to a 110- 88 victory, tying the best-of-seven series at two games apiece and wounding the hopes of the Bucks’ title-starved fans. Everyone within the Bucks’ universe had embraced the notion that Giannis, perhaps the most gifted player of his generation, would lead Milwaukee to its first NBA championship in 50 years, and they knew reaching the summit was improbable without him.

Lasry joined Giannis and the medical staff inside the locker room, anticipating bad news — ligament damage seemed inevitable. But the preliminary examination produced a more hopeful diagnosis, later confirmed by an MRI: a hyperextension of the knee with no tears. Giannis had escaped serious injury and would need just a few days’ recovery time.

The Bucks not only stayed alive without their rehabbing superstar, but they thrived, sweeping the next two games and advancing to the finals against the Phoenix Suns. Giannis returned in time for Game 1, resumed his role as a virtually unstoppable force, and powered Milwaukee to a basketball title the city hadn’t experienced since a young Lew Alcindor (later Kareem Abdul-Jabbar) was lofting skyhooks for the Bucks.

With victory assured in the closing moments of the deciding Game 6, the fans inside the Fiserv Forum erupted, their joyous cheers echoed by another 100,000 people who’d gathered outside the arena to shout into the June sky.

“In those final moments, a huge sense of relief came over us. Then it was jubilation,” Lasry says. “It’s true that you have to be really good, but you also have to be a bit lucky and have things fall in the right place. So when you know you’re going to win, you’re like, ‘Yes! Thank God!’ It was a fabulous feeling.”

Celebrating a title with some of the world’s best basketball players would once have seemed a distant dream for Marc Lasry, who was born in Morocco and came to the United States with his father, a computer programmer, and his mother, a teacher. The Lasrys lived in a modest two-bedroom apartment in Hartford, Connecticut, with Marc and his sisters, Sonia and Ruth, sharing a room until he left for Clark in the summer of 1977. “In that kind of living situation, you can either become really close to your sisters or you can absolutely hate them,” he laughs. “Fortunately, we were very close.”

Indeed they were. Sonia Gardner ’83 and Ruth Lasry Steinberg ’86 would eventually join their brother as Clarkies.

An accomplished student, Lasry loved basketball, and played his freshman year under ultra-ambitious Clark coach Wally Halas, who soon began assembling power-house teams to compete in the NCAA tournament. “They really started recruiting people then, and got very good. I was hoping they’d just stay OK and I could play all the time,” Lasry says with a smile.

He speaks with great affection of his Clark days. Of being a history major and studying under legendary professor George Billias. Of the good friends he made during his four years at the University, and with whom he remains connected today. Of meeting Cathy Cohen ’83 on the first day of school in 1979, falling in love, and marrying three years later.

He also recalls squeaking by on little cash and a lot of ingenuity. When he lived off campus, Lasry and his buddies snagged $20 in carpet remnants at a sale at the Holiday Inn and hammered them into the apartment floorboards. His bed, including the mattress, was a castoff he found at the Salvation Army. He even managed to cadge free meals in the dining hall through an inside connection.

“When you’re 18, everything seems great,” he says. “You don’t even realize how disgusting your room is or the things you don’t have.”

“I loved Clark,” he continues. “It was the right place at the right time for me. I grew up pretty sheltered, and I wasn’t that sophisticated. Clark was a nice stepping stone to introduce me to the world.”

****

After graduating from Clark, Lasry earned his juris doctor from New York Law School. He clerked for the chief bankruptcy judge of the Southern District of New York, and when he graduated from NYLS went to work in the bankruptcy division of the Manhattan law firm Angel & Frankel.

Despite his legal acumen, Lasry had different ambitions. He and Cathy had begun a family — they would eventually have five children — and Marc wanted a job that paid better and engaged his talents and interests. He joined a small investment firm and discovered that he not only loved the work, but was very good at it. In 1989, he and Sonia co-founded Amroc Investments, and in 1995 the two launched Avenue Capital Group, whose primary focus is investing in distressed debt and other special-situations investments in the United States, Europe, and Asia. (The Lasry siblings remain close professionally as well as personally: Marc is Avenue’s CEO, Sonia is president, and Ruth is a managing director.)

Read about how Marc and Cathy Lasry are building a legacy at Clark

Much of Avenue Capital’s success has hinged on Lasry’s ability to perceive opportunities where others may not.

“My skill set is that I can look at something and do the work to understand it. Then, even though you and I have the same facts, I’m going to put a higher value on certain things than you will,” he says. “You might see problems that, to you, make it a bad investment, and I might say, ‘This can be turned around.’

“Basketball is much easier to explain,” he adds. “I can say the reason I’m good at basketball is because I’m too quick for you to cover me, or I’m a great shooter. But with investing, I find it more difficult to describe because it doesn’t always make perfect sense. I just try to take a complicated situation and simplify it so that others can understand it.”

His ability to synthesize the complexities of Wall Street has made Lasry a highly sought-after interview on business programs airing on MSNBC, CNBC, and Bloomberg, where he shares his insights about the market.

****

While high finance has its obvious rewards, Lasry never lost his passion for basketball. He invested in the Brooklyn Nets with hopes of becoming a principal owner, but when he learned that the Milwaukee Bucks were for sale, he was intrigued — with reservations.

This was a struggling team: Besides owning the worst record in the league, the Bucks languished in the bottom 10 percent of every business metric, from ticket revenues to the number of jerseys sold.

Still, as he often did with failing companies and under-performing stocks, Lasry saw potential. In May 2014 he inked a deal to become co-owner of the Milwaukee Bucks with fellow majority owner Wesley Edens.

“I thought it would be a great opportunity — something super interesting and fun. There was clearly a lot of room for improvement, but you only invest in something because you believe you can turn things around,” he says. “I felt if we hired the right people we could get the team into the top half of the league. Then we’d have to establish a new identity, build a new arena and training facility, and hopefully in the next five to 10 years we could end up being one of the five- to 10-best teams in the NBA.”

While Lasry knew the challenges he faced, he was unaware that he had a secret weapon. The year before he purchased the Bucks, the team drafted a skinny 6-foot-11- inch player with a sunny disposition who’d been raised in Athens, Greece, by Nigerian immigrant parents.

“Giannis was just this sweet kid who was always in the gym working out,” Lasry recalls. “Our GM at the time said he had a lot of potential and hopefully he could be an all-star. It turned out that Giannis is not only a talented player, but he’s a phenomenal individual. He cares about the organization and cares about the city. We’re lucky to have him.”

The Milwaukee Bucks kicked off the 2021–22 season with a ceremony awarding the members of the organization their mammoth, diamond-encrusted championship rings. The first to receive one was Marc Lasry. He delivered brief remarks, thanking the fans, before concluding with a line that exhilarated the crowd inside the Fiserv Forum.

“To Milwaukee,” Lasry said, raising his left fist into the air, the arena’s lights glinting off the jewels in his newly awarded ring. “The beginning of many, many championships!”

With Giannis once again dominating on the court, the Bucks are aiming to make good on their fans’ expectations of a repeat championship. Marc Lasry believes if they stay healthy, they can do just that. This June, Milwaukee may roar yet again.