Clark students learn what’s cooking in the chemistry lab

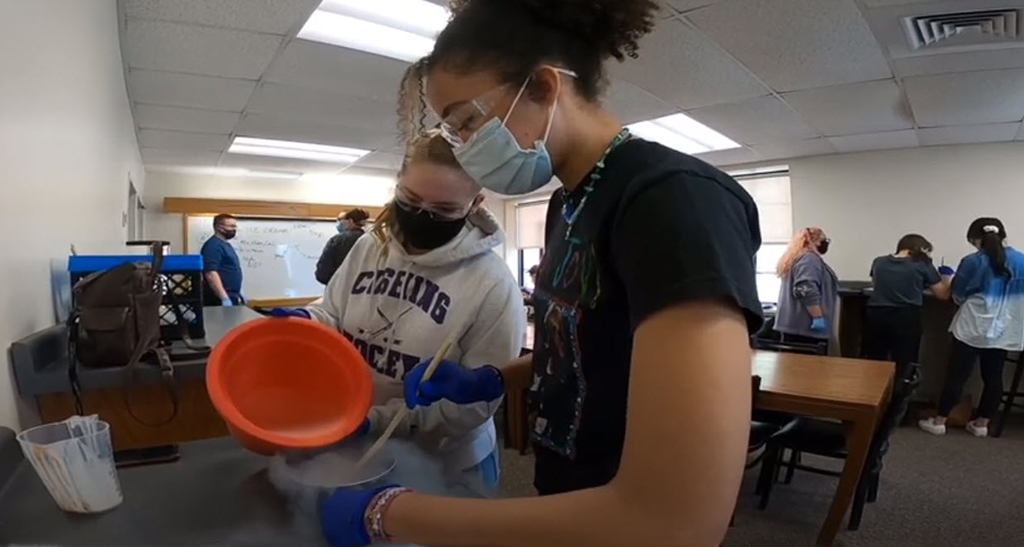

On a recent afternoon, chemistry students in Professor Donald Spratt’s lab carefully measured out whole milk, heavy cream, and chocolate syrup, added the ingredients to a pot, and stirred in liquid nitrogen to slowly freeze the mixture.

The experiment, which produced edible chocolate ice cream, is one of several lab sessions in Spratt’s Kitchen Chemistry course that illustrate how basic chemical principles can be applied to cooking. Considered by some to be the original, most widespread form of chemical research, cooking alters the chemical properties in food. Throughout the semester, Kitchen Chemistry students study these changes by making everything from butter to root beer.

“The idea behind the course is to improve scientific literacy and give people a better idea of what’s going on in the food they eat,” says Spratt, assistant professor of chemistry and biochemistry at Clark. “Some people think that food chemistry is the first chemistry to ever come about, so it’s interesting to talk about why we get different flavors and aromas — these are the chemical processes that are happening as we change our food to make it edible.”

Story continues after video

Spratt developed the idea for the new course, which was launched this semester, after connecting with Dr. Joe Schwarcz and Dr. David Harpp from McGill University’s Office for Science and Society — an organization that aims to demystify science for the public and separate sense from nonsense. The Office for Science and Society at McGill’s work often discusses interesting scientific topics in the news, particularly with food, and Spratt was inspired to develop a curriculum at Clark about chemistry that happens in the kitchen.

“I thought this would be a great opportunity to get students who are not chemistry or science majors into a room to talk about chemistry in a lighter way, but also a really relevant way because they are going to hopefully appreciate what’s going on in their food and understand the processes a lot more,” he says.

Kitchen Chemistry explores the chemical properties of food preparation, consumption, and nutrition through interactive learning. The course includes three lectures per week and a biweekly lab session during which students get hands-on experience with different food chemistry topics. During the first lab session, students examined the pH of different solutions commonly found in the kitchen. Subsequent sessions involve making butter, ice cream, and root beer, and students end the semester by making pickles.

“Having a more critical eye about what’s going on in the world when it comes to science, whether it be different articles, separating fact from fiction, and making good, informed decisions about their diet are the types of things I hope they take away from this course,” Spratt says.

During the ice cream lab, students separated into small groups who were each assigned a different recipe. One group made ice cream using whole milk, another used cream, and the third used an equal mixture of both. When the experiment was complete, Spratt asked the students to sample each variety and describe its taste and texture, then rank the texture on a scale of one to five (with five being the closest to commercial ice cream).

The class learned how air is incorporated as the mixture is churned to increase overall volume. Cheaper ice cream has more than 100% air incorporated, which results in a product that melts quickly and stores poorly, according to Spratt. Premium ice creams and gelato have less than 25% air incorporation, which is why a pint of premium ice cream can weigh the same amount as a quart of cheaper ice cream.

After the session, the class was assigned a lab report with specific questions about the process and properties of ice cream.

“It’s a lot of fun,” Spratt says. “They all wear safety glasses and there’s lots of smoke kicking around from the liquid nitrogen. It looks like an evil chemistry lab, but it really isn’t. It’s just a fun experiment and a quick way to make some ice cream.”

Throughout the course, students also watch videos and complete online activities produced by McGill’s Office for Science and Society that cover scientific literacy and give them a chance to reflect not only on what’s happening in the kitchen, but also about food chemistry in society as a whole.

Students finish the course with a final project about their favorite recipe and the chemistry involved in making the food taste good. After everyone has presented, Spratt shares copies of each recipe to create cookbooks for all of the students in the course.

“Students will be able to share recipes with each other and carry that forward wherever they go,” he says. “They can become better cooks in general — that’s the goal of this course.”