Professor Ora Szekely captures fieldwork experiences of social scientists

What do you do if you get stuck in an elevator in Mogadishu? How worried should you be about being followed after you interview a ring of human traffickers in Lebanon? What do you do if you end up in the hospital far from home? These aren’t just hypothetical scenarios, but real dilemmas social scientists have encountered while conducting field research.

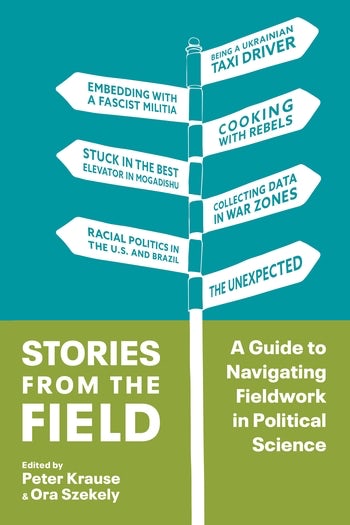

Stories like these — both harrowing and entertaining —make up the pages of “Stories from the Field: A Guide to Navigating Fieldwork in Political Science,” a recently published book from Columbia University Press co-edited by Ora Szekely, associate professor of political science, and Peter Krause, associate professor of political science at Boston College and research affiliate at the MIT Security Studies Program.

Stories like these — both harrowing and entertaining —make up the pages of “Stories from the Field: A Guide to Navigating Fieldwork in Political Science,” a recently published book from Columbia University Press co-edited by Ora Szekely, associate professor of political science, and Peter Krause, associate professor of political science at Boston College and research affiliate at the MIT Security Studies Program.

The personal and professional narratives in “Stories from the Field” come from 44 scholars with diverse backgrounds. They illuminate a side of fieldwork that isn’t often shared: scholars must dodge or quickly adapt to tricky health and safety hazards and other unexpected challenges while exploring the answers to the research questions they dreamed up at home.

Along with the book, Szekely and Krause host a Stories from the Field podcast in which they talk to political scientists about the ethical and logistical aspects of fieldwork. They also address how COVID-19 has affected fieldwork in an article in the journal PS: Political Science and Politics.

We spoke with Professor Szekely about the book and why it was important for her to publish it.

What are your favorite chapters in the book, and why?

While I don’t think I can pick a favorite, one chapter I think is particularly powerful is Amelia Hoover Green’s, in which she writes about not liking field research very much. This isn’t something we talk about much in political science or in the social sciences in general, and I thought it offered a critical perspective.

What kinds of lessons emerge from the scholars’ reflections?

A priority for us in putting this book together was to make sure our contributors reflected the diversity of our field in terms of their research focus, preferred methodologies, and personal backgrounds. As such, the lessons vary widely, from “make sure not to put diesel in a conventional engine” to “try to reflect on the ways in which your own identity can shape your perceptions and interactions during the research process.”

Who will enjoy it? Who should read it?

We’re hoping this book will be of interest to a wide range of readers. This might include faculty and students preparing to do field research, whether in their own communities or on the other side of the world; students thinking about study abroad opportunities; or anyone interested in how the social science “sausage” gets made.

What prompted you to publish this? Why is it significant?

The idea for this book came out of a lunchtime conversation at a workshop a few years ago, when a group of us were sitting around swapping stories about field research, and reflecting on what we’d learned from those experiences. It struck us afterward that these conversations are invaluable, even though they tend to happen informally. So, we wanted to keep growing the discussion in our field about the aspects of field research that can be hard, confusing, unpredictable, or even just unexpectedly hilarious. The chapters our contributors sent us exceeded our expectations in every conceivable way, and we are so, so grateful to them for sharing their stories.

“Stories from the Field” is available from Columbia University Press, as well as on Amazon and other online booksellers. Cynthia Enloe, a Clark research professor and renowned feminist scholar, says she wants every first-year political science student, all graduate students, and her colleagues to read the book.

“Szekely and Krause deliver the real deal: how to do rigorous field research while remaining candid, agile, and curious,” Enloe writes. “In every chapter here, I laughed and I learned.”

Szekely conducts fieldwork across the Middle East to research the foreign and domestic policies of non-state armed groups in the region, including Hamas, Hezbullah, the PLO, the PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party), and others. She also is affiliated with Clark’s programs in Peace Studies and Women’s and Gender Studies. Learn more about her research, as well as her teaching and advising, here.

Her previous books include “Insurgent Women: Female Combatants in Civil Wars” (2019) and “The Politics of Militant Group Survival in the Middle East: Resources, Relationships, and Resistance” (2017).