Nita Winter’s wildflower photography is a blooming success

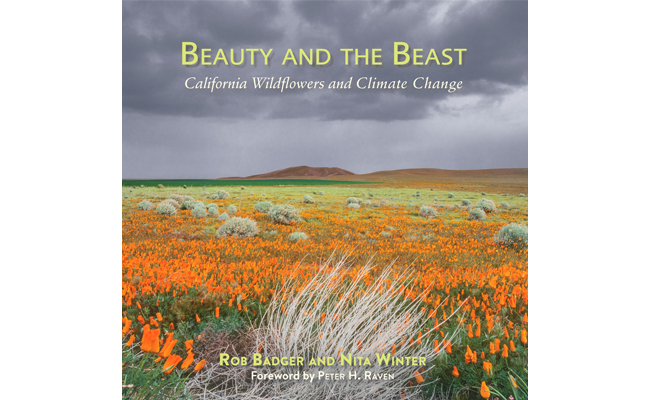

Nita Winter ’76 and Rob Badger had never witnessed anything like it. As far as the eye could see, fields of brilliant orange wildflowers blanketed California’s Antelope Valley Poppy Reserve, rippling like waves as the wind swept across the ground on a spring day in 1992.

The incredible “superbloom” was the first of its kind in nearly a decade. Badger had visited the poppy reserve earlier in the week, and after seeing the stunning landscape, he immediately called his wife to tell her about what he had just experienced. “You just have to see this,” he told Winter.

A few days later, the couple made the seven-hour drive back to the Mojave Desert from their home in San Francisco where they spent the next several days creating breathtaking images in the poppy reserve.

The trip sparked a lifelong passion for conservation photography, and compelled Winter and Badger to spend the next 27 years photographing wildflowers on public land across the western United States. Their goal was not only to capture beautiful images, but to advocate for land conservation and action against climate change and species extinction. The couple was recently honored with the Sierra Club’s 2020 Ansel Adams Award for Conservation Photography after publishing an illustrated coffee table book and accompanying traveling educational exhibit, “Beauty and the Beast: California Wildflowers and Climate Change.”

“We are not just looking for pretty pictures,” the Sierra Club nominating committee shared with Winter and Badger. “We are looking for photographers who use their work to help further a conservation cause. We were all struck by the stunning photos and the combination of art and activism that was reflected in the book.”

Winter grew up on Long Island and studied biology at Clark University. She met her future husband at a photo lab in California in the 1980s while waiting to pick up prints. Winter had moved to northern California after college to spend a summer working as a wildland firefighter and later landed jobs with the National Park Service and the Bureau of Land Management. Eventually, she moved to San Francisco and began volunteering for the Women’s Building of the Bay Area — a women-led, nonprofit community space that was the first of its kind in the country.

The position exposed Winter to new people and places, and she decided to turn her photography hobby into a full-time venture, beginning a project called “Children of the Tenderloin” that documented life in San Francisco’s toughest neighborhood. “That launched my career as a people photographer and I ended up having my work reproduced in the Village Voice,” she says. “I started working with the Children’s Defense Fund, so for the next 25 years I focused on creating healthy communities and celebrating diversity.”

While at Clark, Winter took numerous art classes, including a six-week photography course at the Worcester Center for Crafts. Her father loved sharing his passion for photography with his daughter, and once Winter began taking her own pictures, she quickly fell in love with the medium.

After Winter and Badger discovered the Antelope Valley Poppy Reserve in 1992, they traveled when they could, embarking on three- to four-week excursions to document wildflower superblooms that have become increasingly frequent due to climate change. In 2010, they met with a representative from Blue Earth Alliance — an organization that supports photography projects documenting environmental and social issues — and found a way to use their images to advocate for conservation. With Blue Earth’s support, they created their art-to-action project, “Beauty and the Beast: Wildflowers and Climate Change.”

“Climate change was being talked about, but not very much,” Winter says. “We were learning about how it was going to affect the wildflowers and their natural communities, and we realized we had an opportunity to approach this topic in a unique and subtle, but powerful way. It’s not polar bears, it’s not melting ice, but it’s just as critical. That’s when we realized we could address climate change, land conservation, and species extinction all together.”

To support their work, Winter and Badger were commissioned to create fine art prints and architectural installations from their nature and wildflower images for hospitals and medical centers.

In 2009, Badger won a Wildlife Photographer of the Year award from the British Museum of Natural History and BBC Worldwide. After crowdfunding enough money to travel to London to accept the award in person, Badger decided to put together a book of photographs to bring with him.

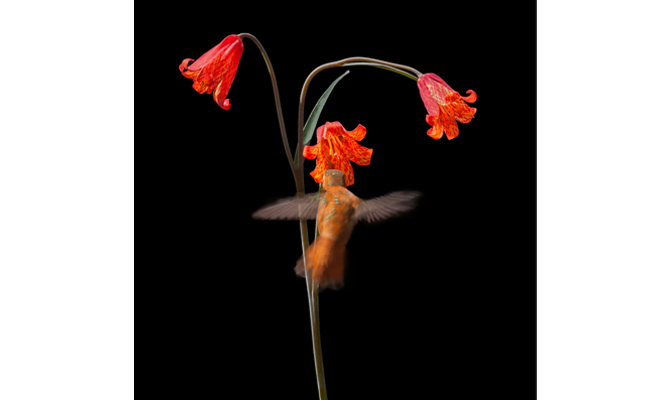

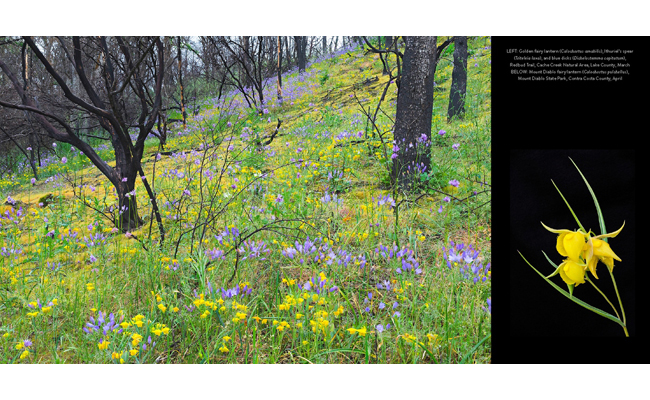

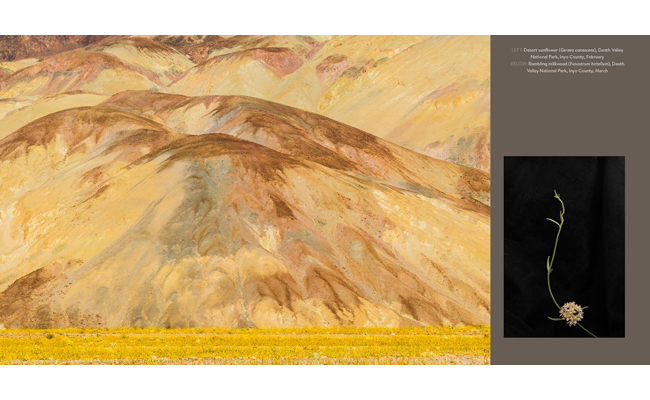

“We feverishly put the book together with a whole collection of photographs within a week,” he recalls. “By that time, I had converted to digital photography, which allowed the two of us to do more macro photography and floral portraits, so the book was not just about landscapes, it was about all the different closeups of wildflowers we were finding on these public lands.”

The couple later brought this early book to the San Francisco Public Library where, in 2016, they hosted a 100-image exhibit focusing on California’s wildflowers. They then turned their attention to creating the exhibit’s companion coffee table book, contacting a diverse group of scientists, environmental leaders, and nature writers to submit short essays. “It was about beautifully weaving art and science together to inspire hope and action,” Winter says.

Badger and Winter teamed up with the California Native Plant Society to publish “Beauty and the Beast,” which features 18 essays from 16 authors who range in age from 20 to 82, as well as 190 images of superbloom landscapes and floral portraits. The essays and images are divided into three sections — “The Gift of Beauty,” “The Human Connection,” and “Ensuring the Future” — plus a “Behind the Scenes” section about how Winter and Badger create their photographs without disrupting the landscapes around them.

“We have stories about restoration work, we have stories about the origin of California flowers, we have scientists who are out in the field studying the rufous hummingbird in mountain meadows and how climate change is affecting their epic migration from Mexico to Alaska,” Winter says.

The book also includes a 25-step action guide for those hoping to begin making a difference in protecting the fragile wildflower ecosystems being threatened by climate change and other human activities.

Using their own money, as well as donations and funds raised through a Kickstarter campaign, Badger and Winter independently published “Beauty and the Beast: California Wildflowers and Climate Change,” which gave them total control over everything from the book’s title and cover to the content on each page. Since the book’s release, Badger and Winter have won 12 awards from the publishing industry and photography competitions — including the 2020 Ansel Adams Award for Conservation Photography.

“We are a voice for wildflowers and the life that depends on them,” Badger says. “As award-winning conservation photographers, our lives are dedicated to creating change with our images.”

Nonprofit organization Exhibit Envoy began hosting Winter and Badger’s traveling educational exhibit, “Beauty and the Beast: California Wildflowers and Climate Change,” in 2018. The show has been seen by more than 45,000 people so far, and the San Diego Natural History Museum is creating a large-print version of the exhibit, expected to open in early 2021.

“This has always been about the power of art and storytelling — about educating and motivating people,” Winter says. “It’s exciting to see how it’s grown.”