Phillis Wheatley Peters is known as the ‘mother of African American literature’

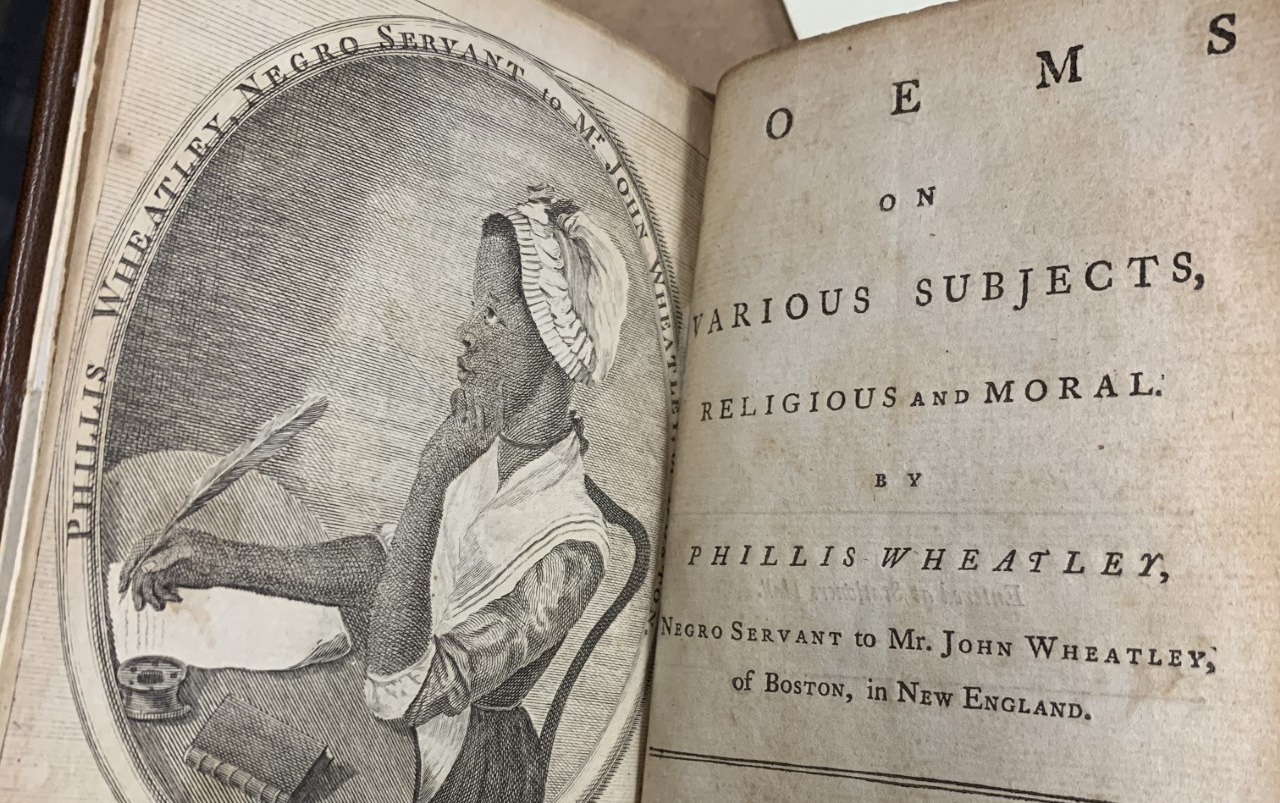

“Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral,” a rare first-edition volume by 18th-century African American poet Phillis Wheatley Peters, was recently transferred from campus to the Museum of Fine Art, Houston to be included in the reopening exhibition of its American wing.

If you visit the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, Texas, you’ll spot a bit of Clark among its displays. The museum is currently borrowing the University’s copy of “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral,” a rare, first-edition volume of work, housed in Goddard Library’s Archives and Special Collections, by Phillis Wheatley Peters — considered by many to be the mother of African American literature. The poems were written while Wheatley Peters was enslaved in a Boston household in the 1760s, and the publication of the volume led to her self-emancipation.

Born in West Africa, Wheatley Peters was kidnapped and sold at the age of 7 or 8 to a slave trader and brought to Boston, where she was sold again to merchant John Wheatley. The family educated Wheatley Peters and eventually she began to write poetry, becoming well known in the city through the family’s connections and from work published in newspapers and pamphlets.

At the age of 20, Wheatley Peters accompanied one of the Wheatley children to London, where she met members of London society, earned the recognition of patronage of the Countess of Huntingdon, an influential evangelical aristocrat, and published “Poems” — becoming the first African American to publish a book and the first to achieve international fame as a writer.

At the suggestion of Huntingdon, the book includes a frontispiece — an engraved illustration opposite the title page — featuring a portrait of Wheatley Peters. The frontispiece would have been created by a different kind of printing than the book itself — and would have increased the value, and importance, of the book, according to English Professor Meredith Neuman.

Neuman teaches “Poems” in her Major American Writers I survey course each year. “It’s a special book,” she says, especially because Clark students have the opportunity to see an original copy in Archives and Special Collections. “It’s deeply meaningful for them.”

“Phillis Wheatley Peters managed to publish her collection of poetry in England, even after American publishers rejected her,” says Luis Santos ’21, an English major with a concentration in Africana studies, who is writing his honors thesis on Wheatley Peters. “Through the Wheatley family and manuscript circulation of her poems, she published ‘Poems’ by navigating a transatlantic, white evangelical network,” using those networks as a means to her ends.

Wheatley Peters returned to Boston prior to the book’s actual publication, and soon received her manumission papers — in other words, she was free. Within several years, she married John Peters, and chose to adopt his name. That’s significant, Neuman says, because her first name was given to her by the Wheatley family — it was the name of the ship that carried her from Africa — and like most enslaved people, her last name was that of her enslavers.

“The book is not just important to history and literature,” Neuman says. “It’s crucial in terms of understanding the early African diaspora.” The work was written in Boston and traveled with Wheatley Peters to London to be published, then back across the Atlantic once printed. Wheatley Peters distributed copies throughout the colonies.

The Clark Archives and Special Collections received its copy of “Poems” in the early 1970s through a gift from Mrs. Winifred Gates, widow of Professor Burton N. Gates, says University Librarian Laura Robinson, who arranged for the volume to be transported to Houston. An art moving company that specializes in transporting rare, unique, and fragile materials “built a custom enclosure for it to be shipped safely.” It is being displayed as part of the Museum’s reopening of its American wing and will be on loan for 1 year, under the care of the museum’s paper and book conservators.

The COVID-19 pandemic made transferring the book to Houston difficult. “Rather than picking it up directly from the library, the shipping company had to build a book enclosure from the back of their truck near Woodland Street,” Robinson explains.

According to Cynthia Shenette, head of access services at the Robert H. Goddard Library, the book is valued between $7,000 and $10,000. The first edition held in Clark’s Archives and Special Collection has been rebound; a first edition with its original binding could be worth many thousands more.