#ClarkTogether

Clark professors ready to welcome students to their online classrooms

The COVID-19 pandemic has altered so many details of our daily lives, it’s almost impossible to quantify them. But as Clark University students resume their classes on March 23 they can be comforted to know that one essential thing about their University has not changed: Their professors remain as committed as ever to shaping a rigorous and fruitful learning experience for, and with, them.

Classes will be conducted through a variety of online formats, and at a safe distance, which will take some getting used to. Professors have been preparing for these new circumstances since the University announced that on March 23 it would move to distance learning. By using the open-source learning tool Moodle and videoconferencing/streaming platforms like Zoom and Panopto, professors have adapted their content and teaching styles for the virtual classroom and are ready to reconnect with their students.

“The technology staff at Clark has been so helpful,” says María Acosta Cruz, professor of Spanish in the Language, Literature, and Culture Department. “And there’s also been masses of instructional advice from colleagues across campus, as well as professional organizations. It’s a learning curve for all of us.

“I’ve been practicing with colleagues,” Acosta Cruz adds, “but seeing what works and what doesn’t is going to be day-to-day. I want to make sure I give students many chances to catch up with the content — which, by the way, hasn’t changed much.”

Shuo Niu, assistant professor of math and computer science, is teaching Introduction to Data Science this semester, which helps students develop skills in data-centered computing and application. Typically, he assists students with solving coding problems during face-to-face lab sessions. “In the virtual classroom. I plan to use the remote desktop control technology on Zoom to help students solve program problems,” he notes. “I can remotely type program codes on the students’ computers while talking to the students.”

Niu will replicate face-to-face interactions using Zoom’s audience feedback tools that allow students to “raise their hands,” vote “yes” or “no” on a particular question or topic, and request that the professor move at a slower or faster pace.

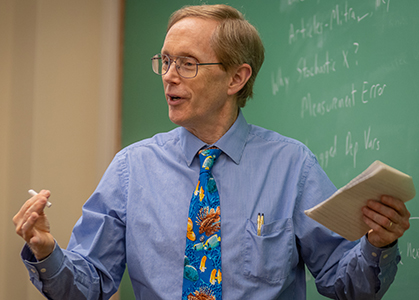

“I’ve been teaching at Clark for 35 years now and haven’t seen anything remotely like the current Covid-19 crisis and response,” says Wayne Gray, professor of economics. “I’ve been impressed by the creativity of my faculty colleagues, as we’ve shared strategies to move courses online. I’m most comfortable teaching with chalk on a blackboard, but Zoom is a good tool for teaching an online class, and with help from folks in Media Services I’m writing with a stylus on an interactive screen — no more chalk dust, starting Monday!”

Some professors are teaching their courses synchronously (in real time), others through asynchronous means, such as through recorded lectures that can be accessed anytime. The latter is especially helpful when a class is composed of students who live in different countries and time zones.

Abbie Goldberg, professor of psychology, is using a mix of technologies to create as complete a classroom experience as possible, with most of the learning to be done asynchronously. “This is essential, in order to manage the many demands that we all have upon us, and our need for flexibility and understanding,” she says. Her students can also expect a bit of fun when they log in. “I’ll be posting lots of cat pictures and nature pictures.”

Virtual teaching can pose a particular challenge to those in the sciences, where lab work is often essential. Donald Spratt, assistant professor of chemistry and biochemistry, notes that while traditional lab work is ramping down, essential student research continues. “My students backed up all of their data so they can work from home on their honors, M.S. and Ph.D. theses,” he says, “and some of them will be defending their theses later this spring.”

Online learning provides a special challenge for performing arts instructors, says Gino DiIorio, professor of theatre arts. “Courses such as Creative Actor, Shakespeare in Action, and Modern Dance obviously call for a lot of face-to-face contact,” he said. “We’re making do with some modifications. For example, a lot of students in Shakespeare are doing monologues; in Modern Dance, they’re researching great choreographers and doing papers on them.”

A number of student productions were shut down this spring, he adds.

“This is the work that doesn’t show up in one’s grade but is part of the artistic experience. Three plays were canceled, a musical, a cabaret, two dance concerts — the list goes on. We’re hopeful that we can bring back some performances next fall once things return to normal — fingers crossed.”

Meredith Neuman, associate professor of English, has used a questionnaire to her students to gauge which teaching approaches will be most suitable to their personal living and working situations. A key question, for instance, is whether the student has reliable access to the internet.

“A lot of what I’ve been doing with the questionnaire is just finding out where students are right now in terms of their ability to connect,” she says. “For example, imagine a family that has multiple people working from home and taking online classes. The demand for even a good internet connection is going to be high. If you are at home rather than at school, there are suddenly going to be other demands on your time. Faculty are getting ready to really understand the various situations students may find themselves in.”

The Introductory Biology course, co-taught by professors David Hibbett, Deb Robertson, and Beth Bone, is a large class whose students live in many time zones on at least two continents. While the professors have transitioned to an online format, they stand ready to mail or fax hard copies of notes and exams to anyone having difficulty with internet access, Hibbett says.

Anita Fábos, professor of international development and social change, has the benefit of having taught an online course last fall. “I learned how to align the learning objectives of each of my assignments with the right tool or technique — something I had long done as an in-person teacher. However, I believe that having to rethink these learning objectives for my online students has made me a stronger teacher in the classroom,” she says. All three of her courses this semester were planned to incorporate community fieldwork, but now will involve solely secondary research. A class she’s teaching with Tim Downs, associate professor of environmental science and policy, concerning migrant and refugee challenges, will not include in-person research but instead will involve field notes, journals, online information, and other sources.

Clark’s new learning situation — as with that of colleges and universities across the country — is premised on the concept of “social distancing” to help prevent the spread of COVID-19. Rosalie Torres Stone, associate professor of sociology, prefers the term “physical distancing” to describe what she and other Clark professors will be practicing.

“When experts recommend ‘social distancing’ they don’t mean social disconnection, social exclusion, and rampant individualism,” Torres Stone says. “We need to find creative ways to maintain social connectedness with our students, faculty and staff and Clark has done just that! We have been given the tools that will help us stay socially connected with our students and our colleagues.

“My plan is to maintain as much consistency as possible with my students while recognizing that it’s not going to be perfect, it may even be messy. But that’s OK. Life is messy right now.”