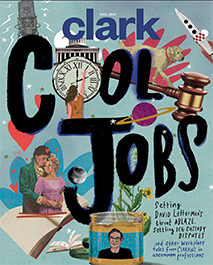

Clark Magazine

Do you know the mustard man?

What makes a job cool? Is it fun, rewarding, unusual, or a combination of all three? → Gotta be all three. → While there aren’t enough truly cool jobs to go around, our alumni seem to have landed more than their fair allotment. So does that mean Clarkies are inherently cooler than everyone else? Read on, and decide for yourself.

Not every attorney gets to argue a case before the U.S. Supreme Court. And of those who have, it’s a safe bet only one has done it with a jar of mustard in his pocket.

Barry Levenson ’70 was an assistant attorney general for the state of Wisconsin in 1987. On the way to court, he saw on a room service tray a small unopened jar of mustard. He had just begun collecting different types of the condiment, so he picked it up and put it in his pocket.

“I argued that case — an important Fourth Amendment case, Griffin v. Wisconsin — with that jar of mustard in my left pants pocket. And I won the case,” he remembers.

The Supreme Court Mustard holds a special place in the National Mustard Museum, which Levenson founded in 1992 (originally as the Mount Horeb Mustard Museum). It moved to its current location in Middleton, Wisconsin, in 2009.

“We’ve got the world’s largest collection of mustards — almost 6,200 different kinds — and hundreds of antique mustard pots and tins,” Levenson says. “There’s also an exhibit about mustard in medicine.”

Levenson was once interviewed by Oprah Winfrey, and almost appeared in a David Letterman segment on unusual collections. Letterman, over Levenson’s warnings, ate a spoonful of a fiery horseradish mustard and fell to the floor, writhing in agony. Levenson’s segment was cut from the show.

Why mustard? It all began on Oct. 28, 1986, hours after the Boston Red Sox lost the World Series to the New York Mets. A Worcester native and lifelong Boston sports fan, Levenson was looking for something to take his mind off baseball and ended up wandering the aisles of a local supermarket. He stopped in front of the mustards. “If you collect us, they will come,” he heard (well, he claims he heard).

And they do. Thirty thousand visitors a year make their way to his museum for exhibits like the Great Wall of Mustard and a new display from Saskatchewan, Canada, the world’s largest exporter of mustard seed. Visitors can take the Curator’s Interactive Food Quiz, consult with confidential condiment counselors about which mustard is best for them, and purchase official memorabilia from Levenson’s mustard “university,” Poupon U.

The museum welcomes 6,000 visitors on the first Saturday of August for the annual National Mustard Day festival, which Levenson has organized since 1991. This year’s theme was “Carpe Dijon” — “ loosely translated as ‘Squeeze the Day,’ ” he quips.

“Every year, it gets bigger. We have all sorts of mustard games — ring toss, spinning wheel, fishing for mustard, mustard bowling — live music, and lots of mustard for the hot dogs and bratwurst,” he says. But don’t expect to see ketchup or mayo. “I’m very much against the lesser condiments.”

The museum hosts the Worldwide Mustard Competition each spring, with about 300 international submissions, including entries from Romania and Sweden. This year’s favorite was the Moutarde du Meaux, a French mustard whose recipe is unchanged since 1632. “It’s a favorite of chefs and foodies,” Levenson says.

When he’s not curating mustard, Levenson teaches future lawyers about food law. He even wrote a book on food-related legalities, “Habeas Codfish” (University of Wisconsin Press, 2001), in which he examines issues like the McDonald’s scalding-coffee case, the cattle ranchers who sued Oprah Winfrey, and how the Mr. Peanut logo shaped trademark laws for the entire food industry.

Levenson has written two other books and two plays, including “No One Goes to Hell for the Food,” which was staged in Madison, Wisconsin, in 2018. “It’s based on a true incident,” he says. “A convicted killer was executed by the state of Oklahoma in 1995. And his last words were, ‘I didn’t get my Spaghetti-Os.’”

Levenson insists his greatest joy is interacting with people who are surprised to find visiting a mustard museum is actually a lot of fun.

Sometimes those visitors are Clarkies, which is the coolest part of a very cool job.