Jen Plante helps students find the wonder in words

Jennifer Plante, M.A. ’00, knows what it means to be a struggling college student with few goals and little guidance. She excelled in science at her Nashua, N.H., high school, but as a first-generation biotechnology student at WPI in the early 1990s, she found herself struggling.

“I didn’t seek out help; I didn’t talk to my adviser. I had every intention of dropping out of college after my sophomore year, going back to New Hampshire, getting a job, and becoming an adult,” Plante says. “Then I took an English class. What I found when I took that class was my passion.”

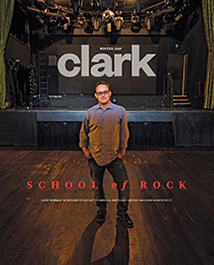

Now director of Clark University’s Writing Center and Writing Program, an adviser in the LEEP Center, and an instructor, Plante has a story to tell students who seek her help. It starts at WPI, where she played basketball against the cross-town rival Clark Cougars. Biotechnology fascinated her, and jobs in the field were plentiful, but she wasn’t thrilled by the idea of working in a laboratory.

Her English class kept her in college. “I had always loved reading and writing, and I especially loved critically analyzing and talking about books,” she says.

The class took her back to childhood, when she pounded out short horror stories on her grandfather’s Royal typewriter. Emulating the gritty, cigarette-smoking scribes of the past, “I would put a pretzel rod in my mouth,” she says. “That was my conception of what a writer was.”

After a stint as a technical writer, Plante earned a master’s degree in English at Clark, and fell in love with the English Department. “I felt like I finally fit,” she says.

She began teaching courses for Clark’s Writing Center and the Writing Program, became the Center’s interim director, and in 2007, she was hired full time.

Through her various roles, Plante teaches, advises, and mentors up to 75 students a semester, from first-year students sorting out their interests to undergraduates in the Summer and Evening Division. She manages a team of peer advisers in the Writing Center who work with undergraduates to hone their writing. She advises humanities majors interested in gaining real-world career experience through LEEP projects and internships, and serves as an adviser for students’ directed studies and theses.

Through it all, she is honest with her students. “I struggle with writing, and I share that with students,” Plante says. “Writing is painful.” She recalls how she failed all her classes the second quarter of her sophomore year at WPI. “When I tell students that, they are very surprised,” she says. “My hope is that they are also somewhat relieved — that this does not define who you are; it’s just a thing that happened, and you learn from it.”

At Clark, Plante’s academic interests have focused on those marginalized by society. With a student, she co-taught a course on Queer Theorists of Color for the Women’s and Gender Studies Program. She developed First-Year Intensive courses on Queer Horror, exploring how monsters are “coded” as queer and tap into society’s anxieties about sexuality and gender. And in Fiction on the Fringe: Crimes, Addictions, and Psychoses, she examined works like “Lolita” and “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.”

Her evening course, Serial Killer Fiction, delves into novels and films like “American Psycho,” “Seven,” and “Natural Born Killers.”

“What we’re really looking at is the serial killer as the embodiment of Americans’ anxieties at the time,” she explains, “and so by looking at the serial killer, you actually learn more about what was going on in America than you do about anything else.”

Plante is now designing a course on superheroes. She is partial to Batman and Batwoman — whom she describes as “canonically LGBTQIA characters” — because “although wealthy, they have no alien powers, and they work hard.”

Plante has laid down roots in the Main South neighborhood. Through a Community Development Corporation program for faculty and staff, she bought part of a multifamily home. She walks to work, and she eats at Fantastic Pizza and Annie’s Clark Brunch, where she enjoys seeing her students. For her, “Main South feels like a small town.”

She tries to foster similar connections in her students, which she hopes will allow them to find their own paths.

“I want my students to have a mentor,” she says. “I want them to come to me and not be as wayward as I was.”