Professor Benjamin Korstvedt examines why tradition-bound Nazis embraced composer’s avant garde music

Music Professor Benjamin Korstvedt

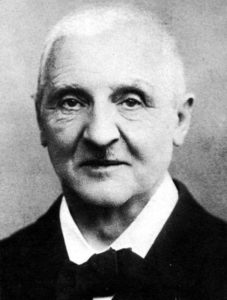

The Austrian musician Anton Bruckner composed musically avant garde, even modernist, symphonies during his lifetime (1824-1896). So why did the Nazis, typically tradition-bound in their aesthetic preferences, co-opt his music for their political ends?

Clark University Music Professor Benjamin Korstvedt addressed that fascinating contradiction in a talk given as part of the Especially for Students lecture series at the Strassler Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies. Beginning in the 1930s, the Third Reich appropriated Bruckner’s music as an exemplar of the German classical heritage in the tradition of Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms. During the Nazi period, his music was used at the Nuremberg rallies, routinely played on radio broadcasts, was performed in government-sponsored festivals, and was the subject of frequent articles in the popular press, and in scholarly publications.

Seeking to avert an imagined spiritual decline, the Nazis promoted traditional Germanic classical music while denouncing innovative musical styles that had emerged in the early 20th century. As with the visual arts, Nazi musical tastes favored conservative and conventional forms, in contrast to modernist work they derided as “decadent,” “degenerate,” or “Bolshevist,” terms tinged with antisemitism.

What made Bruckner appealing was the monumentality of his music, which suited Nazi aesthetics, as well as the perception that he was part of a German musical legacy that embodied national greatness. His origins in upper Austria, the region of Hitler’s birthplace, conveniently underscored Nazi claims about a cultural “bridge” between the German Reich and Austria. And propagandists characterized him using blood and soil terminology.

At the same time, Nazi ideology ignored details about the composer that did not fit their narrative. Thus, the facts that he was not actually German but rather Austrian and never embraced anti-Jewish views, as did Richard Wagner and his descendants, were overlooked. In actuality, during his lifetime, Bruckner enjoyed close relationships with Jewish friends, including his student, Gustav Mahler, and his “artistic father,” the conductor Hermann Levi.

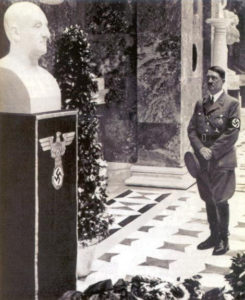

Korstvedt described how the Nazi regime instrumentalized the image of Bruckner. Their fascination and campaign of exploitation culminated with a June 1937 festival devoted to his music in Regensburg. On that occasion, officials unveiled a bust of Bruckner on a pedestal emblazoned with a swastika in Walhalla, the fantasy temple to German culture and history in Bavaria. During the ceremony, Hitler laid a wreath at the base of the pedestal, and Joseph Goebbels extolled Bruckner as a “son of the Austrian soil … that unites the entire German people.” This event was part of a prelude to the Anschluss in March 1938 that annexed Austria to Germany.

In this highly politicized setting, scholarly debates about different versions and editions of Bruckner’s music were hardly objective. These disputes fit into the Nazi’s ideological embrace of German cultural forms which they aimed to free from Judaizing or modern influence.

Korstvedt highlighted the work of Robert Haas, a committed Austrian Nazi and music scholar, who praised Bruckner’s music for its pure German essence. Espousing flagrantly antisemitic language, Haas asserted that a cadre of former pupils, friends, and the composer’s music publisher — all largely Jewish — deceptively doctored the text of Bruckner’s compositions. Haas was committed to producing a critical edition that would restore the oeuvre to its supposedly original form. At the Regensburg festival, Goebbels pledged state financial support to the Bruckner Society, under Haas’ leadership, to publish an officially approved edition that would carry Hitler’s imprimatur. The Nazi investment in Bruckner proved long lasting and his work carried this taint for decades.

Authoritarian regimes, Korstvedt explained, take music more seriously than democratic governments, both to harness its emotional resonance and to control its potentially unsettling political meanings. The case of Bruckner demonstrates how aesthetic symbols can be put in service to totalitarian ideologies. Laying bare the Nazi exploitation of Bruckner, Professor Korstvedt shows the power of music as an emotional force whose meaning can be subordinated to the state. Music turns out to be another important avenue for understanding genocide and underscores the significance of interdisciplinary research and teaching at Clark’s Strassler Center.

Editor’s note: Mary Jane Rein is executive director of the Strassler Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies.