Kettle pond researcher seeks answers below the surface

Linnea Menin’19 grew up near the Atlantic Ocean, in Newburyport, Massachusetts. At Clark University, however, she has discovered that you can attend college further inland and still conduct marine biology research in iconic waterways, like Cape Cod and Walden Pond.

Funded by the University’s Steinbrecher Fellowship and Summer Scholars Program, Menin has worked with Assistant Professor Nathan Ahlgren and doctoral candidate Emily Dart on a study of the microbial communities — the types of bacteria and other microorganisms — found in 11 kettle ponds on Cape Cod. These rounded, sediment-filled ponds formed thousands of years ago when retreating glaciers scraped off layers of soil and left behind chunks of ice, which eventually melted and pooled in the sand.

The three biologists also have focused on Concord’s Walden Pond, a kettle pond made famous by 19th-century author Henry Thoreau, and several ponds and reservoirs in Worcester.

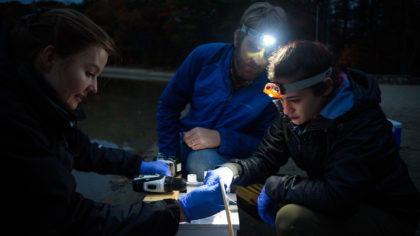

They took water samples at all of the ponds, spending a week at the Cape this summer and visiting Walden Pond several times over the past year.

Back in the Ahlgren Lab at Clark, they processed samples and extracted microbial DNA, which they sent off to be sequenced. They also studied the makeup of nutrients and the amount of chlorophyll in the samples to determine the ponds’ health.

“Once we have the DNA sequences back, we will use bioinformatics tools to determine the composition of the microbial communities in each of the ponds,” Menin says. “We hope to incorporate the results into a public outreach campaign to educate the public about how to better care for the ponds.”

Last spring, a study published in PLOS One raised concerns about the water quality of Walden Pond, drawing the attention of media across the world. “Please stop peeing in Walden Pond, researchers beg,” read a Boston Globe headline. “Pee and pesticides: Thoreau’s Walden Pond in trouble, warn scientists,” noted The Guardian of London.

The media coverage came right in the middle of the Clark researchers’ work.

“All the press has been about peeing in the pond, but a lot of the data surrounding the impact of swimmers urinating in the pond has already been estimated” by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), Menin says. “We’re more interested in the more concrete issue of the septic tank placement.”

State officials moved and replaced the septic tank for the Walden Pond visitors center several years ago, she explains. Groundwater samples she, Dart, and Ahlgren took from around the edge of the pond last fall revealed a significant decrease in nitrate concentrations compared to samples taken 20 years ago, preliminarily indicating the tank removal will help improve water quality.

John Colman, one of two researchers involved with the earlier USGS report, taught the Clark team how to take samples at the same locations he had used 20 years ago. The researchers will continue to monitor the groundwater to see if the trend continues, Menin says.

The Cape Cod ponds may face similar issues with human contamination, yet at a lower level. “We believe that there is probably less contamination from human contact in the Cape Cod ponds because they are more isolated,” she says. “Walden, on the other hand, receives more than 500,000 visitors each year.”

A biology major, Menin added a concentration in mathematical biology and bioinformatics to gain skills and experience in that ever-expanding field. She is writing a thesis about her pond research for Clark’s fifth-year Accelerated B.A./Master’s Degree Program in biology.

“This project has given me lots of experience with both lab work and field work,” Menin says. “I now know how to write research grants and how to present scientific findings in a comprehensive manner. I’ve also been able to better hone my lab skills like sample collection and preparation, and DNA extraction and sequencing.”

The pond project builds upon the experience that the Traina Scholar gained her first year, working in the lab of biology professors Susan Foster and John Baker. She has interned at New England Biolabs (NEB), a well-known genomic research company, where she met two Clark alumni — Cathy Rezac ’03, M.A. ’04, a production scientist, and Jessica Brown, M.A. ’91, executive director of the NEB Foundation — and presented her work in a company-wide seminar.

Last spring, Menin served as a peer learning adviser for a forensics course at Clark, helping prepare the labs and design a “crime scene.” Outside of academics, she’s on the executive board of J Street Clark U and works as a proctor and supervisor at the Bickman Fitness Center.

For Menin, Clark’s small size is a plus. “I chose to attend Clark because I liked the small class sizes and the tight-knit community. Clark also has a reputation as a college that values collaboration over competition, and the campus is both beautiful and conveniently compact.

“I love how accessible the professors are,” she says. “The ability to do research with a professor relatively easily is a valuable part of the major.”

After graduate school, Menin hopes to apply her biology degrees and interest in nature and wildlife to a career that combines fieldwork and lab work, perhaps for the National Park Service or in environmental policy.

“All of my work in the lab and the field has been very instrumental in helping me figure out what I want to do in the future,” she says.