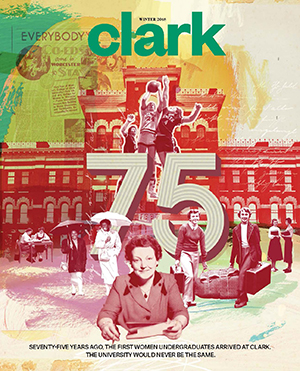

‘We were here because we wanted a good education’

“You musn’t make waves.”

Hughes, at her desk in 1952

So went the motherly advice of Hazel Hughes to the 73 students who had arrived on the Clark campus in fall of 1942 as the University’s first women undergraduates. Hughes was hardly timid, but as the director of student activities for the newly launched Women’s College, she knew dramatic change was coming to Clark, and believed her young charges should ease their way onto the overwhelmingly male campus.

Nine months earlier, the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor, and as men were siphoned into the war effort, women were presented with educational and professional opportunities they had long been denied. They seized their moment, and the country, the culture, and Clark were about to be transformed.

Waves were inevitable.

In the shadow of war

During the Great Depression of the 1930s and early 1940s, the possibility of admitting women to Clark University’s all-male undergraduate college was under debate. In the wake of the nation’s dire economic situation, men’s enrollment in the undergraduate college was fluctuating, and the University’s endowment had shrunk. To remain viable, the University needed students to bring in revenue. But while Worcester’s liberal arts colleges competed for male students, no similar opportunity existed for academically inclined women. As such, Clark’s administration identified a market niche waiting to be filled.

In his endowment establishing Clark University, founder Jonas G. Clark stipulated the institution’s purpose was to educate young men. To accommodate female undergraduates, the University established a legally distinct Women’s College that would share faculty, administration, classroom and library facilities, and curricula with the Men’s College.

The reaction of male undergraduates and faculty to the announcement, while mixed, was not characterized by significant resistance. As Clark historian William Koelsch wrote in his book “Clark University, 1887-1987”: “Once the deed was done, the male students and faculty largely welcomed the women undergraduates both as individuals and as parts of the college organizations.”

The late H. Martin Deranian ’45 confessed to being delighted at the news that some of his classmates would be female. “I was ecstatic! I felt privileged to see this happen,” he said in a 2015 interview. “I didn’t know what to make of it all. I was really kind of in awe.”

Campus life at Clark during the war years was certainly not a typical undergraduate collegiate experience for the 73 women (approximately one-third were transfer students) who entered Clark in fall of 1942, or for the 269 men enrolled that year.

The late Effie Vranos Geanakoplos ’43, who transferred to Clark in the fall of 1942, was one of several undergraduate alumnae interviewed by Ashley C. Rondini ’97 and Lauren Almquist ’97 in the mid-1990s for their research paper “‘The Legitimate Invasion’: An Oral History Celebration of Clark’s Pioneer Women, 1942-49.” Geanakoplos told the authors her graduation day was “a blend of joy and sorrow. A lot of the boys were going to go off to war, and, before that date, casualty lists were coming in every day. We were all very aware of the dangers, and it was very sad.”

Those who joined the Women’s College embraced the chance to earn a liberal arts degree.

“We were all here [at Clark] because we wanted to be here,” said Phyllis Freeman Gustafson in a 1986 interview with members of the Class of 1946. “The University was sought out by each of us. We were here because we wanted a good education.”

Some women sacrificed deeply to be among this historic class. When Barbara Norris Andersen ’46 announced she was enrolling at Clark, her mother demanded she instead attend Radcliffe, a family tradition. A defiant Barbara packed a single suitcase and got a friend to drive her to Worcester. Her mother was so enraged that she disowned Barbara, refusing to speak to her daughter ever again.

Once they’d arrived, the women proved themselves on every front. Their exemplary performance in the classroom assured the administration and faculty that Clark’s academic standards would not be compromised. Pleiades was established in 1945 as the women’s counterpart of Gryphon, the men’s honor society, and five years later, when a chapter of Phi Beta Kappa was established at Clark, three of the first five initiates were female. Women assumed leadership roles in clubs and organizations across campus. They rowed crew and played basketball in the basement of Jonas Clark Hall, a.k.a. the Women’s Gym, which required them to pass and dribble around the grove of pillars that held up the building.

Acceptance wasn’t universal among the men. An April 30, 1943, editorial in The Scarlet opposed adding women to the Athletic Council and objected to women being awarded the same “Block C” insignia — the varsity letter — as the men for their participation in varsity sports.

Ann McKenny Early ’46 counterpunched in her Scarlet sports column, decrying “the misogynists [who] just didn’t want us,” noting that the women athletes were “insulted in assembly.” From that point on, she cheekily retitled her column “Block C’s.”

There were instances of sublime collaboration.

Women’s student body president Margaret “Peg” Russell ’46 successfully allied with Stanley Gutridge ’45, president of the men’s student body, to improve the study environment in the library by drafting rules for appropriate behavior, which, if violated, could result in academic penalties.

“Clark looked into the future,” Gutridge said in a 2016 interview. “They knew men were off to war and women were pushing ahead, stepping into jobs and working for social and economic equality. It was really a learning experience for all of us, but a very good one. Clark was preparing us for the reality that once we headed out into the world we needed to go forward together.”

More than holding the fort

women undergrads filled classrooms on campus

While the number of students in the Women’s College doubled between the 1942-43 and 1944-45 academic years, male enrollment in 1944-45 barely reached 30 percent of what it had been three years earlier. With the men’s numbers much reduced, it fell to the women to maintain Clark traditions like Spree Day, publications like the campus newspaper and yearbook, and cherished student organizations such as the Glee Club, the Boheme Committee and the Clark University Players Society. For more informal fun, the Women’s Lounge hosted marathon games of bridge played with the same zeal brought to today’s video games.

In the 1986 interview of Clark women, Harriet “Heidi” Burack Lewitt ’46 reflected on how campus life changed as the men’s numbers dwindled. “It had altered because we were running all the organizations,” she said. “We were not only holding the fort, we were given that opportunity because we were here, and [the male students] weren’t. It was less of a competitive thing than sort of the norm. We could become head of whatever group it was.”

In August 1945, Japan surrendered to the Allies, ending the Second World War. Returning servicemen, buoyed by the G.I. Bill, flocked to colleges to begin or finish their degrees. “By the time a lot of them came back, [women students] were an established fact, and much more accepted,” Sue Colton Arnold ’46 recalled in the 1986 interview. “There wasn’t this, ‘Do we want you here?’ We had been here. They were coming back and had to be received and acclimated.”

‘The women had arrived’

The actions and attitudes of members of the Clark University faculty were crucial to the success of the Women’s College. The almost entirely male faculty, with a few exceptions, was accepting and encouraging of their female students. Thelma Brodsky Lockwood ’45 recounted the note a professor had left in her final exam book that read, “I questioned women coming to Clark University, and now I apologize.”

“I thought that was beautiful,” Lockwood said. “I felt, well, the women had arrived.”

The most loved and enduring figure in the Women’s College, M. Hazel Hughes, watched over her co-eds with protectiveness and affection from 1942 until her death from cancer in 1968. Hughes was energetic enough to serve as the women’s first basketball coach, and mature enough to act as trusted mentor and mother-confessor as she rose to the position of dean of women. It was under her watch, in 1962, that women were given permission to entertain male visitors in their rooms (on Sundays from 2 to 5 p.m.), and that the curfew for sophomore, junior and senior women was eliminated in 1966.

The place Hughes held in the hearts of Clark’s women, particularly the players on her basketball teams, during those early decades was recognized in 2011 with the installation of a plaque in her honor outside Jonas Clark Hall Room 001, the former Women’s Gym.

Dueling destinies

Like many at the time, Clark’s early women struggled with determining if their destinies lay in traditional roles as wives and mothers, as career seekers, or as both. In 1948, the Advisory Board for the Women’s College proposed that a curriculum focusing on “human relations” should be available to female students, on the grounds that “the most important function of women in the contemporary world is that of wife and mother.” The University never adopted the proposal, but it spurred a master’s thesis that included a survey of 107 alumnae of the Women’s College. Some supported the board recommendation; others were dismissive. “Clark is not a trade school,” one respondent said, “and I did not go there to learn to keep house.”

The homemaker vs. college graduate dilemma helped Betty Friedan’s bestselling 1963 book, “The Feminine Mystique,” resonate with college-educated women. The book has been credited with sparking “second-wave feminism,” which contributed to widespread activism by female students at Clark and other colleges and universities during the 1960s and the ’70s. The need of many women to put their college degrees to good use would bring profound change to the country, and to Clark.

The Women’s College is not mentioned in Clark’s academic catalog after 1968, and there was no dean of women appointed after Hazel Hughes’ death that same year. Marcia Savage ’61, M.A.Ed. ’62, Ph.D. ’66, L.H.D. ’92, would assume many similar functions in her role as dean of students, and later as the first female dean of the college from 1975-79. During that decade, the number of Clark women appears to have reached 50 percent of the undergraduate student body.

Savage recalled the respect accorded to her in her administrative position. “What I thought was fascinating about Clark, and my relationship to it, was how they felt when I was the only woman on the provost’s council during a very difficult period. I was serving with faculty members who had had me as a student. But they did very well with me. They gave me the due that I was owed at that point.”

Changing times

Women’s Basketball Tournament

By the time the 1960s had drawn to a close, women slowly had begun to assume more administrative and faculty positions at Clark. In 1962, Alice Cooney Higgins became Clark’s first female trustee, and five years later was named chair of the Board of Trustees, the first woman in the United States to hold that position at a private research university. She proved to be an influential and forceful leader for the length of her tenure.

In 1921, with the appointment of Ellen Churchill Semple to the faculty of Clark’s newly established Graduate School of Geography, the male monopoly on instruction at the University was breached. But it wasn’t until 1963 that a female faculty member, English Professor Jesse Cunningham, was granted tenure. In 1977, Education Professor Helen Kenney became the University’s first female department chair.

The 1970s at Clark reflected the social changes sweeping the nation. Title IX, guaranteeing women equal opportunity in education, was signed into law in 1972. Starting that same year, women’s varsity sports, beginning with basketball, gradually returned to campus after having been demoted to club sport status in 1952.

Clark women advocated for changes to the curriculum that shed a scholarly light on the contributions of women, debated how women had been portrayed in the scholarly record, and planned their futures.

Seventy-five years after arriving on campus, Clark women continue to change the game as leaders in medicine and business, the arts and education, science and the law. They are shaping our world at every level in every field, fulfilling the promise of those 1942 pioneers. And they provide daily inspiration for future generations of Clarkies, both men and women, by doing what they’ve always done best.

They make waves.