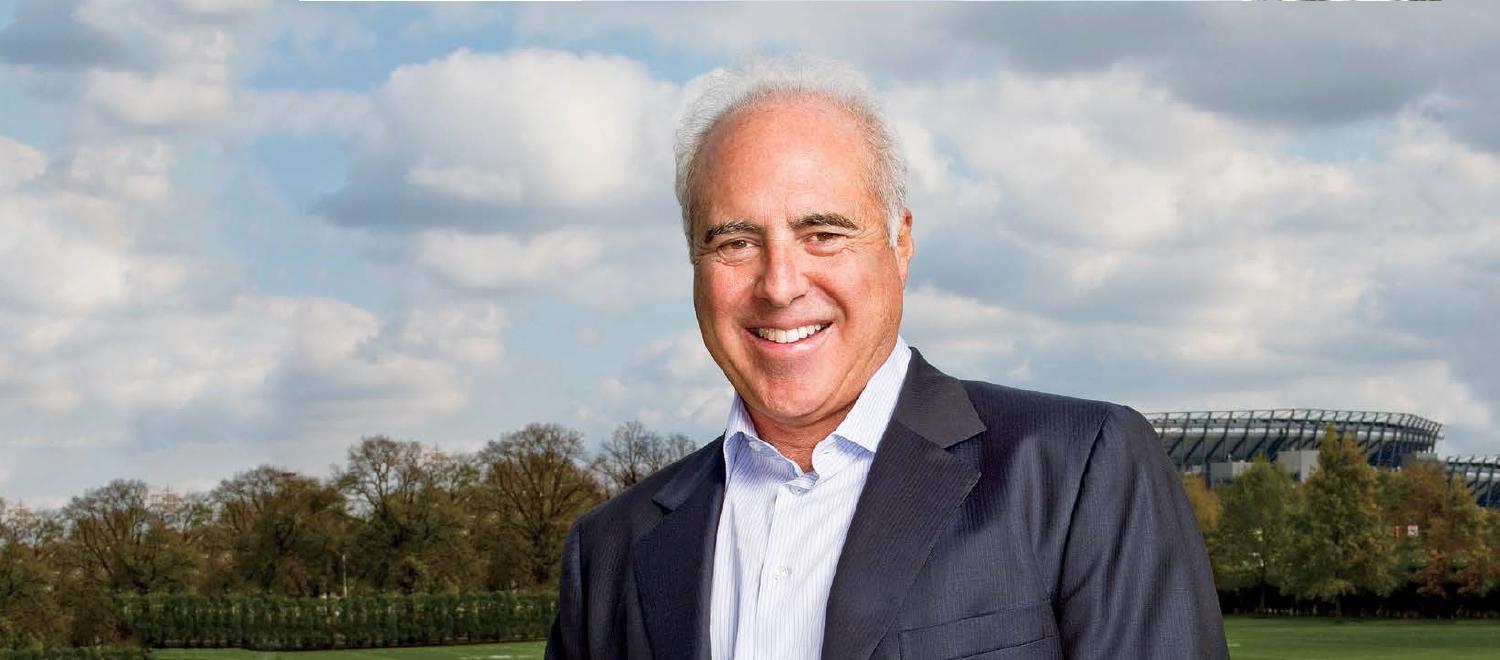

Editor’s note: As the Super Bowl approaches, Clark is rooting for alum Jeffrey Lurie ’73, owner of the Philadelphia Eagles, who are taking on the Kansas City Chiefs in the big game. We are republishing this fall 2013 CLARK magazine profile of Lurie, which describes his journey from Boston kid and Clark undergrad to the highest echelons of the NFL.

The mayor was on the line, welcoming Jeffrey Lurie ’73 to town as the new owner of the Philadelphia Eagles, when a rat skittered across Lurie’s office floor. As omens go, it was a doozy. Things didn’t get better the next morning when The Wall Street Journal ran a front page story taking Lurie to task for overpaying for the franchise — a then-record $185 million — and for making the purchase based on the heat of emotion rather than cold analysis. The numbers just did not add up, the paper insisted. It was early May 1994. As Lurie sat in that basement office in Veterans Stadium, a dismal facility widely regarded as one of the worst in the National Football League, he pondered the newspaper’s admonition.

“I wasn’t self-confident enough to think they weren’t right,” he recalls with a laugh.

But Lurie knew something his critics didn’t. He had approached this business deal methodically, studying the figures, poring over the projections, and extracting sentiment from the equation before pulling the trigger — something he would do time and again in the succeeding years.

And there was one more thing, his personal wild card, so to speak. Lurie was entering the NFL as a second career. His first had been in the film industry, which helped him assess his newly chosen profession in a unique light. He saw the NFL games as hit movies playing to eager audiences every weekend, and as the number of avenues to distribute the product was multiplying, the potential for an explosion in football’s popularity loomed on the horizon.

Paid too much? Lurie was figuring the team had been undervalued. That rat in his office was not a premonition of doom. It was a call to action to rebuild a proud franchise that had fallen on hard times and catch the wave he believed was forming.

Jeff Lurie stood at the podium in Tilton Hall on May 17 and told the Reunion Weekend audience who’d come to hear him speak that Clark University represented a reversal of the rigid prep school education he’d received.

“At Clark, it wasn’t just a professor determining what the paradigms of the moment were,” he said. “I didn’t want to hear the paradigms as they existed; a lot of us wanted to hear the paradigms of what could be. That notion infused me with a lot of energy to go after things that others would say were conventionally unrealistic.”

In a recent interview, Lurie remembered that Clark’s emphasis on emotional intelligence and critical thinking “liberated what was inside of me and allowed me to flourish.”

“What I really respect and value about my time at Clark was that the school focused on empowering students to explore and not be fixated on any rigid form of analysis, but really be open to the world around them,” he says. “Clark wasn’t what was important — the student was important.”

Days were for class; the nights included trips to El Morocco, the Miss Worcester diner and any of the dozens of rock and folk shows that passed through Worcester and Boston (sometimes with stops at Clark). A Grateful Dead fanatic, Lurie followed the band across New England whenever it swung through the Northeast.

The Boston native was fervent about his hometown sports teams to the point where he would sleep overnight outside of Boston Garden to snag tickets for obstructed-view seats to Bruins games. When the Celtics reached the playoffs, he and his Clark buddies camped outside the Ticketron office in the parking lot of the Auburn Mall to be the first in line for tickets. “I got to know the lady in charge there,” he recalls. “She was very helpful.”

Lurie graduated from Clark with a degree in psychology, earned his master’s at Boston University and his Ph.D. in social policy from Brandeis. Though he enjoyed a stint teaching at B.U., he had no interest in becoming an academic. His two loves were sports and movies, and a career that didn’t involve either of them simply was unthinkable.

Shortly after earning his doctorate, Lurie joined the family business, General Cinema Corp. The company was founded in 1935 by Lurie’s grandfather, Philip Smith, and at its peak could boast of being the largest movie theater chain in the country.

“My grandfather came up with the concept of opening a movie theater in a shopping mall in the suburbs, which was unheard of in those days,” Lurie says. “People would go to the city for entertainment, and suburbs were just places to live. He built the first cinema in a shopping mall in America — at Shoppers’ World in Framingham [Mass.] — and at first nobody showed up because the concept was so new. He brought in stars of the day like Mae West and Marlon Brando to perform live on weekends so people would realize that there could actually be entertainment in the suburbs.”

Lurie dove in. As the company’s liaison to the Hollywood studios, he learned the mechanics of production, distribution and finances. Cable TV channels like HBO and Showtime were appearing on the scene and altering the industry’s dynamics, and movie companies were forced to adjust.

Within a few years, Lurie, tired of the movie exhibitor side of the business, left the company to form Chestnut Hill Productions and produce his own movies in Los Angeles.

“I’d gotten to know a lot of top Hollywood executives through my job at General Cinema and it was a natural move for me,” he says. “I’d become less interested in the movie theater business and more interested in what kinds of movies you could make.”

As another learning experience, his time in Hollywood was invaluable. He gained an intimate understanding of the movie and TV industry while producing a number of feature films from the late 1980s through the mid-1990s, including “I Love You to Death” with Kevin Kline, “Blind Side” with Rebecca De Mornay, and “Foxfire,” starring a then-unknown Angelina Jolie. “Even in those days you couldn’t take your eyes off her,” he says of Jolie. “There was a charisma about her, a sort of live spirit. It was no surprise to me that she gained the success she did.”

Obtaining financing within the Hollywood studio apparatus proved difficult, especially for a newcomer like Lurie, and he was forced to abandon projects about which he was particularly passionate. One of those unmade films, “The Tunnels of Cu Chi,” told the harrowing story of the sophisticated underground strongholds built by the Viet Cong during the Vietnam War and the U.S. “tunnel rats” who infiltrated them. Despite the star power of Kevin Costner behind the film, it never got made.

“The movie looked at the Vietnam War not just through the eyes of American G.I.s, but also from the Vietnamese point of view,” Lurie says. “The story would have dealt with the human aspect of what it’s like to fight for your country, and also the complicated nature of being a tunnel rat. At the time it was too controversial for a studio to finance a movie that wasn’t told only from the Western perspective.”

Even during his years on the West Coast, Lurie maintained his fanatical devotion to the Boston sports scene. In the pre-satellite dish days, he would drive hours to find any place that was airing the New England Patriots games — to a small Santa Barbara motel or across the border into Arizona. Once, on a trip to Santiago, Chile, he talked his way into police headquarters and into a stark room with a tiny television to catch the Pats in the playoffs.

As it turned out, Lurie wasn’t just watching games. He was planning his next move.

Jeff Lurie’s love of football dates back to the legendary 1958 championship game between the New York Giants and Baltimore Colts, which he watched on television with his father, Morris. Dad was a Giants fan; young Jeff favored the Colts because he liked their quarterback Johnny Unitas and he preferred their uniforms. The Colts won the overtime thriller in what has been branded “The Greatest Game Ever Played,” and Lurie was hooked.

In the early 1990s he actively pursued his goal to own a sports franchise, putting together the financing for a bid to buy his hometown team, the Patriots. He lost out to Bob Kraft and then turned his attention to another club on the market, the Philadelphia Eagles, a team with a storied history, yet one that had experienced little playoff success for more than a decade.

Lurie’s bid of $185 million won him the team, but at what cost? He was inheriting a franchise that appeared to be on a downward trajectory. The fans were alienated, the players clashed with management, the employees had grown disheartened, and the team’s relations with the Philadelphia community had frayed. The Eagles also competed in a city-owned stadium so dilapidated that it prevented the team from attracting top-notch players and coaches. The rat in Lurie’s office was only one in an army.

Though Lurie knew the reality laid out before him, he also perceived the potential in this drowsing juggernaut. His experience in the movie business had offered him an insider’s view of how changing broadcast models could transform an industry. Cable television and satellite were changing the landscape.

“In those days there was really a split between the entertainment industry and sports; people didn’t look at it as integrated, but we were just starting to see the explosion in the ways the sport could be distributed,” he says. “We would be making hit programming on a global scale.

“It was scary because it was the first really big acquisition where I was risking a tremendous amount to take this opportunity. I couldn’t let my dream to own an NFL team confuse the analysis; the analysis had to come first. Eventually, it all came together.”

Lurie went to work, hiring a management team and coalescing financial and community support for the construction of the state-of-the-art NovaCare Complex and the $500 million Lincoln Financial Stadium, an environmentally friendly facility outfitted with solar panels and wind turbines that produce much of the building’s electricity.

Off the field, Lurie and his staff built a culture of community stewardship through the creation of the Eagles Youth Partnership. The nonprofit serves more than 50,000 low income children in the Greater Philadelphia area every year with a focus on health and education programming. EYP takes its services directly to the schools and neighborhoods with mobile programs — the Eagles Eye Mobile and Eagles Book Mobile — that have led the way for other organizations to emulate. In addition, each year, team members, from Lurie on down, build a playground in a disadvantaged neighborhood and remain connected with charitable organizations throughout the city and beyond. Lurie notes that the Eagles’ training facility features the Hall of Heroes, which is adorned with portraits, not of football players, but of Jonas Salk, Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, and other scientists, humanitarians and activists whose accomplishments shook the world.

In 2011, the Eagles were named the Team of the Year by Beyond Sport, an organization that promotes, develops and supports the use of sport to create positive social change worldwide. The award recognizes the top sports team in philanthropy across the globe. In addition to his charitable efforts within the organization, Lurie devotes his time to autism research on a global basis.

“I’d always admired what the Red Sox did with the Jimmy Fund regarding cancer research, so when I bought the Eagles I made it a high priority that what we do in the community should be of equal priority to what we do on the football field,” he says. “That’s the way we’ve operated, inculcating in every player who we’ve brought in that they’re not just joining a football team, they’re also having an impact in the community.”

On the field, Lurie and his football operations team built a winner, eventually hiring Andy Reid as coach and drafting Donovan McNabb at quarterback, a pairing that made the Eagles perpetual playoff contenders and led them to the 2005 Super Bowl (which they lost 24-21 to the Patriots).

Today, he notes, despite struggling in the 2012 season, the team boasts a 60,000-person waiting list for season tickets, which is emblematic of Eagles fans’ near-mythic zealotry (memorably depicted in movies like “Invincible” and “Silver Linings Playbook”). In 2013 Forbes valued the franchise at $1.3 billion.

Lurie resurrected the flagging Eagles so resoundingly that it inspired Harvard business professor Rosabeth Moss Kanter to chronicle the turnaround in her book “Confidence: How Winning and Losing Streaks Begin and End.” In assessing Lurie’s job as owner, Kanter wrote:

“[Every] turnaround starts with the same overriding challenge: the need to make unpopular decisions about a situation whose full ugliness has been denied, and yet, at the same time, restore people’s confidence that they can start winning again.”

Lurie has made those tough decisions. In 2010 he traded McNabb, and last year he parted ways with Reid — who has more wins than any coach in franchise history — and hired University of Oregon coach Chip Kelly as his on-field general. The moves were personally wrenching (Lurie remains close with both men and presided over McNabb’s induction into the Eagles’ Hall of Fame), yet emotion was put aside for the overall health of the team.

In 2009 Lurie made the controversial decision to hire quarterback Michael Vick after he had served 21 months in federal prison for his involvement in a dog-fighting ring. Vick’s return to the football field was denounced by many; Lurie says bringing him back to the NFL “boiled down to the notion of second chances.”

In 2009 Lurie made the controversial decision to hire quarterback Michael Vick after he had served 21 months in federal prison for his involvement in a dog-fighting ring. Vick’s return to the football field was denounced by many; Lurie says bringing him back to the NFL “boiled down to the notion of second chances.”

“If somebody has performed his jail time and satisfied the entire penalty, then society needs to give him a second chance,” he says. “Michael has been a wonderful teammate and a model citizen since we’ve given him that second chance.”

Any story about a man who once earned a living making movies deserves a Hollywood ending, and Lurie’s is no different.

Five years ago Lurie and his then-wife Christina (they’ve since divorced; Lurie is remarried) launched a documentary-film company, Screen Pass Pictures. He’d never been able to produce the kinds of feature movies he’d wanted during his years in Hollywood, and he saw the surging popularity of documentaries as a new opportunity to address important issues through film.

“There was a time when it wasn’t worth it to make a documentary that might be seen by eleven people. Today, you can see documentaries in movie theaters, on HBO, Showtime, PBS. They’re finally getting distributed, and they’re having an impact.”

The company’s 2010 film, “Inside Job,” detailing the global financial crisis, earned the Academy Award for best documentary film. Last year, the Screen Pass film “Inocente,” which chronicled the plight of a young undocumented immigrant artist, won the Oscar for best documentary short.

“It’s humbling,” Lurie says. “I’m proud of it, but you don’t make a film because you think it’s going to win an Academy Award. You take on an issue, align yourself with talented filmmakers, and go from there.”

The success of the NFL is like a blockbuster movie playing in real time. Contracts with the TV networks rake in billions (with good reason: the games dominate the ratings), Fantasy Football leagues are an obsession for millions of fans, and the Super Bowl has evolved into a de facto national holiday.

And the Clarkie who refused to be rooted in old paradigms when new models were crying out to be invented, the guy who sat in a bleak basement office 19 years ago and was told by The Wall Street Journal that he’d made the biggest mistake of his life, could be forgiven if he simply sat back and said, “I told you so.” But that would require dwelling on the past when the future is so much more intriguing.

This story was originally published in CLARK Magazine, fall 2013.