Too fat. Too skinny. Too short. Too tall.

Dumb. Slow. Bad hair. Bad skin. No style.

The insults are like darts that land precisely where a girl might feel most vulnerable. They may be launched by a classmate, a teammate, or even a “friend.” More insidiously, the messages are reinforced on television, in music and magazines, and through social media. The cumulative effect can be devastating.

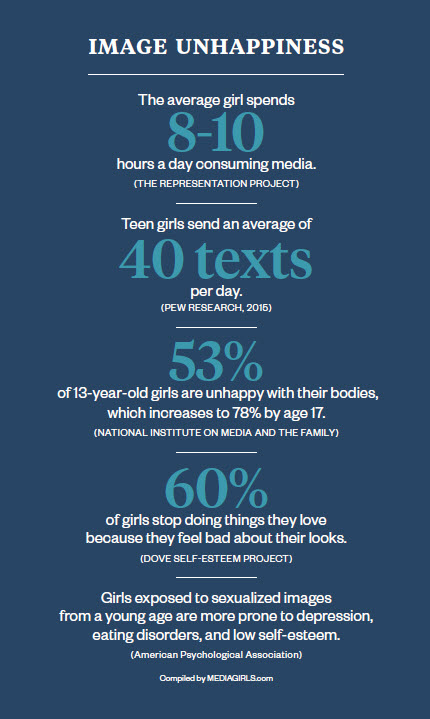

Michelle Silver Cove ’91 is fighting back. Two years ago, she founded MEDIAGIRLS, a nonprofit that teaches middle school-age girls to examine, critique and change sexist and other negative messaging that diminishes girls and young women. MEDIAGIRLS instills in girls the confidence to create their own positive platform. Their empowerment matters, Cove says, because many adults wrongly assume girls understand the depth of the media’s influence on their self-perceptions. “They are inundated with 10 hours of media a day. If no one stops to talk about how manipulative media can be, how would they know the messages aren’t true?”

Her education program builds awareness that helps girls assess why the media pushes impossible beauty standards and recognize how ads influence attitudes. Participants use social media to write and post content about women who inspire them. They evaluate music videos and ads, and speak up on behalf of girls everywhere.

Cove is no neophyte to the world of media. She came to Clark from Tulane University as a junior (the fall after her brother Eric ’89 graduated) and jumped right into media and communication studies. Her award-winning journalism has appeared in national publications, and she’s written books on parenting and families, including “I Love Mondays” and “Seeking Happily Ever After” and co-authored “I’m Not Mad, I Just Hate You!: A New Understanding of Mother-Daughter Conflict.”

As a filmmaker, Cove directed and produced the documentaries “Seeking Happily Ever After,” which explores how single women are redefining personal happiness, and “One and Only,” about the joys and struggles of one-child families. “I’ve always loved media,” Cove says. “It’s the greatest storyteller in the world and has the potential to inspire and motivate.”

But it also can do damage, particularly online.

“Social media is where they live, and it’s intense,” Cove says of the younger generations. Some parents restrict their children’s social media use; others block it outright. “What few parents and educators are talking about is how to use social media for good.”

When Michelle Cove’s daughter, Risa, was 9, she took an unusually long time emerging from the locker room for a favorite swim lesson. Cove found her inside, eyes filled with tears, refusing to come out. After gentle questioning, her daughter explained why: “When I stand up tall, my thighs touch each other.”

“I am a feminist media maker, and I can’t protect my daughter from this?” Cove recalls thinking. “How many girls will get hit with this and why isn’t anyone doing anything about it?”

Shortly afterward, Cove overhead two more young girls critiquing their thighs, the depth of their vulnerability revealing itself to her. From that conversation, the idea for MEDIAGIRLS was born.

In summer 2014, Cove piloted MEDIAGIRLS with a group of eight girls in Brookline, Mass. Since then, 240 students have participated in the program at Boston-area schools, including 75 girls this spring. The program, for girls in grades six to eight, lasts eight to 10 weeks and is taught by college-age female interns, whom Cove trains in intensive two-day sessions. They follow a structured lesson plan in which participants are taught to critique media images, decide what they want to see, and learn how they can change the narrative.

She says middle school girls are paddling against a tide of negativity. In a typical MEDIAGIRLS exercise, a group of girls is asked to list eight positive qualities about themselves. Three or four items usually come easily, but after just a few minutes the girls are stuck. Some can’t think of anything else worth listing. Others who list a full eight are reluctant to admit it, for fear of being accused of bragging.

“Middle school is exactly when girls start losing their voice and stop speaking up,” Cove says.

Giving them the ability to effectively engage with media becomes a powerful tool to counteract that reluctance. “It’s not only about understanding and deconstructing the media, but also being part of the solution,” she says.

MEDIAGIRLS strips away the messages about what girls “should be” so they can celebrate their authentic selves, says Laura Johnson, associate dean for student affairs at Boston University’s School of Education and a member of MEDIAGIRLS’ board of directors. Most young girls post a carefully “curated” self on social media, she says, to the point where the true self suffers.

While Cove has created a program, MEDIAMINDS, for both boys and girls to explore media’s influence, MEDIAGIRLS is strictly for girls. This allows them to express their true selves in deeply personal, and absolutely critical, discussions that would never occur in a mixed-gender group.

MEDIAGIRLS classes begin with a simple question: Whom does the media consider a “perfect” girl?

“Many will say they are all perfect girls, all beautiful, because they know it’s what adults want to hear. Then our teachers will say, ‘True, but what does media tell us?’” Cove says.

That opens a deeper, candid conversation. Girls are being asked to compare themselves to unattainable ideals, many of them constructed through digital artifice, like Photoshop and other image-altering software. “There’s a multibillion-dollar industry to make girls feel bad,” she says. “It’s a wake-up call when girls learn they’ve been sold a story to get their money.”

MEDIAGIRLS exposes the flaws in this narrative. One of the favorite tools is critiquing magazine ads with the hashtag #xomg. Girls can draw an “x” on negative messages or circle ads they think are on target. They then post the marked-up ads on social media or even send them to the advertisers. If the girls are hesitant to post, Cove does it for them from the MEDIAGIRLS site.

“If you want girls to be part of the solution, you have to tap into the anger” generated by the immense pressure on them to be something they are not, or ever will be, she says. “There’s power in knowing you don’t have to buy into this story, and you can use your voice at 11, 12, or 13 to make a difference right now.”

Social media is a mixed blessing. It connects people like never before in history, yet also keeps them at a distance from one another — an unsettling dissonance.

The girls’ online presence is a matter of deep discussion in Cove’s classes. She relays the results of a CNN poll of eighth-grade girls that finds they typically use social media for defensive reasons: to monitor if they are being excluded from something, or to search out cruel things others have said about them. “There’s high pressure to be part of that world, and not for the joy it brings,” she says.

MEDIAGIRLS conversations touch on wide-ranging topics, including what the girls see as their value to the outside world and to themselves. Participants also get to choose a woman who inspires them — not for her looks, but for who she is and what she has accomplished. They ponder what the world might be like if these qualities were the media’s focus.

Cove would love to take MEDIAGIRLS nationwide, and those around her have little doubt she will expand her impact. “Not only does she have the passion, but she goes out in the world and does something with it,” says Johnson.

The self-described “shiny” moments — when girls use their voices to effect real change — keep Cove going. “We are planting seeds and changing girls in real time,” she says. “It’s why I’m doing this.”

This article was published in the summer 2017 Clark magazine