Sometimes it’s the human who gets hooked

Scientists often borrow from nature when developing some of their best ideas. Look no further than earthworms. Their squiggly, tunneling movements have already inspired researchers to dream up robots that could inch along the ground in military reconnaissance missions, or create devices that could thread their way through digestive tracts and other tight spaces in the human body.

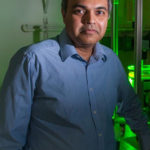

Thanks to a LEEP project this summer and a directive study course this fall, Bernny Ramirez ’18 is getting in on the ground floor of the next phase of this biologically inspired engineering and physics research. He’s working in the Complex Matter and Nonlinear Physics Laboratory of Arshad Kudrolli, professor and chair of physics, reviewing scientific journal articles and running experiments involving earthworms’ movement.

“We are trying to understand how organisms and robots move through media which are not quite liquid or solid,” Kudrolli says, like sand and water, clay, sludge and even fluids in the human body. He has published research in Physical Review journal about the swimming speed of microorganisms in such fluids.

Kudrolli’s earthworm research is new to his lab.

“Our goal is not only to understand how these organisms move underground, but also learn from the techniques they use under various water content, and develop our own examples of optimal robots,” he says. “For a while, we have wanted to study earthworms in our lab, but sometimes the right student has to come along with the right motivation for it all to fall into place. Bernny has made great progress on their biomechanics.”

About Bernny Ramirez ’18

For Ramirez, the research has been challenging because, unlike undergraduates who are working on Kudrolli’s longer-term research projects, he cannot rely on prior lab notes.

“This research is really new to the Kudrolli lab. I started out with a clean slate,” Ramirez says. “This can involve a lot more outside-the-box thinking compared to what you do in a classroom.”

To observe the worms’ movement up close, Ramirez places the red wigglers, or Eisenia fetida, in a glass tank full of hydrogels – the same gooey, translucent beads used in diapers and plant arrangements. Each time, he uses a different size bead, ranging from 1 centimeters to 2 millimeters, to see how the worms’ movement changes.

“We take image sequences and then use Matlab software to analyze the worms’ movement,” Ramirez explains.

sometimes the right student has to come along with the right motivation for it all to fall into place,” says Arshad Kudrolli, professor and chair of physics. “Bernny has made great progress on their biomechanics.”

He has discovered that he can directly apply what he has learned in the physics classroom while also practicing techniques and methods that he never could pick up in a lecture or textbook.

“I found myself organizing data and research better,” he says. “Although this is still a challenge, I have gotten a taste of thinking critically to make a problem as simple as possible and get a better foundation on it.”

Ramirez might seem an ideal candidate for this project, which merges biology with physics and engineering. He’s loved biology since taking courses in at The Calhoun School on New York’s Upper West Side. And he drew upon his interest in biology when interning during high school at the American Museum of Natural History, where he taught school groups and other visitors.

“My favorite area of biology would probably be anatomy because I find body functions to be extremely interesting. I want to pursue bioengineering after graduation, so I’m happy I got to combine both my interests — biology and physics — for my LEEP project,” Ramirez says.

Clark’s small physics classes and his close interactions with faculty have helped Ramirez succeed. “That’s something I really love about Clark — the attention that professors give to their students.”

And now that he’s dug into earthworm research, Ramirez is pursuing an even more direct path to his end goal.

“My research project definitely connects to my plans,” he says. “Studying movements of worms has implications for drug delivery, and that’s bioengineering.”

Some people look at a worm and see bait. Ramirez sees the future.