Five undergraduate and two master’s degree students who completed Clark University’s spring biology course titled “The Genome Project” have received the ultimate feedback for their research and coursework: vetting of their research by professional scientists and acceptance of their publication into the American Society for Microbiology’s Genome Announcements.

Their article, titled “Genome Sequence of Zymomonas mobilis subsp. mobilis NRRL B-1960,” appears in the journal’s current issue and stems from a spring Problems of Practice (PoP) coursetaught by John Gibbons, an evolutionary genomicist and assistant professor of biology. PoP courses provide Clark undergraduates with internship-like experiences within an academic context.

“For undergraduates, opportunities to play a big role in a research project are rare, which is one of the primary reasons I developed The Genome Project (BIOL 209),” Gibbons says.

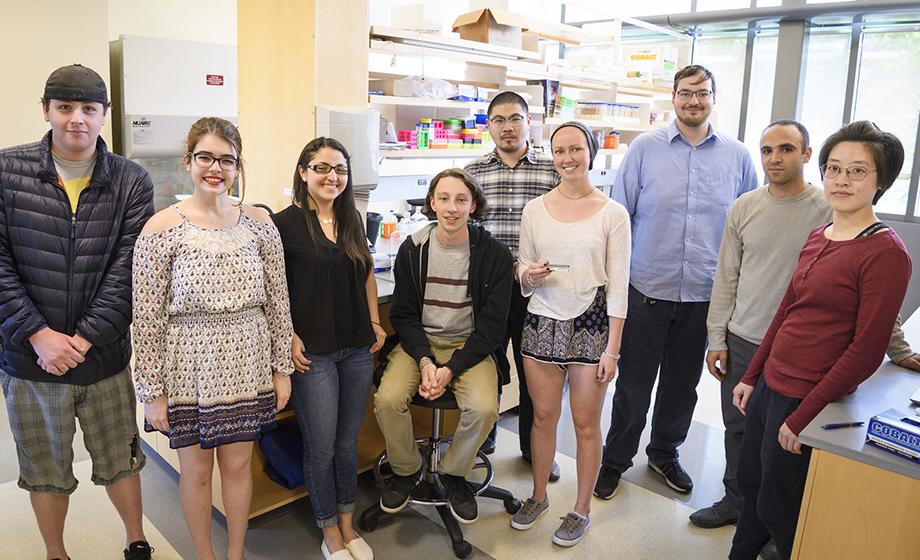

The first author on the paper is Katherine Chacon-Vargas, a doctoral student in Gibbons’ lab who worked with the undergraduates, including Alexandra Chirino ’18, Meghan Davis ’17, Sophia Debler ’17, Wynn Haimer ’18 and Justin Wilbur ’17, an incoming fifth-year master’s program in biology student ; and fifth-year M.S. in biology students Ethan Wainblat ’16 and Baxter Worthing ’16, M.S. ’17. Two doctoral students at Clark also are co-authors: Xiaoli Mo and Shu Zhao.

Each semester, Gibbons’ PoP course gives students the opportunity to achieve a first for them — and for science as a whole: piecing together the DNA blueprint of an organism with no existing reference genome.

This year’s students sequenced the DNA of Zymomonas mobilis, a bacterium isolated from spoiled cider in Scotland. They obtained the sample from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

“By far the most rewarding aspect of this course was witnessing discovery. It’s something that drives me as a scientist, and it was exciting to watch students experience this for themselves,” Gibbons says. “In one instance, three groups, using entirely different methods, independently discovered a set of genes that were unique to our isolate of Zymomonas mobilis. The whole class was talking about TonB receptors (proteins found in the outer membranes of the bacterium) for a couple weeks after that.”

Gibbons’ lab focuses on domestication of microbes like Z. mobilis.

“If you think about how dogs were domesticated from wolves, we study how microbes were domesticated,” Gibbons explains. “In the case of Zymomonas mobilis, we know it’s been used by humans for thousands of years, but we don’t know if it’s been domesticated, and that’s what we’re trying to learn.”

Z. mobilis can lead to spoilage in cider and beer, but it also can be deployed to create alcoholic beverages such as pulque, a popular drink made in Mexico from the fermented sap of the agave plant.

Even more, the microbe can be used to produce ethanol for biofuel. For that reason, the U.S. Department of Energy is interested in such research.

“This bacterium has a unique biochemical pathway that allows it to produce ethanol more efficiently than yeast, which the biofuel industry is currently using,” Gibbons says.

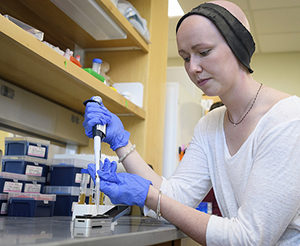

To sequence the genome for Z. mobilis, students gained experience in bioinformatics, collecting and analyzing large volumes of data. They wrote code in the Linux computer language and developed methodologies by piecing together analysis from several open-source algorithms, employing Clark’s High Performance Computing Cluster. They presented their results at Clark’s Academic Spree Day this spring.

“We compared all the sequenced strains of Zymomonas mobilis, trying to find the unique genes in our particular strain, and we found there were 52 unique genes in comparison to all the other six strains,” explains Chirino, a biology major who plans to concentrate in bioinformatics. “It was fun to learn on the job. I got to see how much I like using computers; I could test myself.”

Haimer — a biology major who plans to apply to Clark’s fifth-year management (M.B.A.) program, then head to medical school — says bioinformatics is a useful skill to add to his résumé.

“Bioinformatics is where this field is headed — that junction of biology and computer science,” he says. “This course was fun, and although I don’t know if bench work research is necessarily what I want to pursue for my career, I’m hoping that whatever I do will open as many doors as possible.”