Hospitals, schools and sports facilities all watch for signs of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), a bacteria that resists many antibiotics. Although MRSA infection rates dropped 31 percent between 2005 and 2011, it still kills more than 11,000 Americans per year, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control.

Hospitals, schools and sports facilities all watch for signs of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), a bacteria that resists many antibiotics. Although MRSA infection rates dropped 31 percent between 2005 and 2011, it still kills more than 11,000 Americans per year, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control.

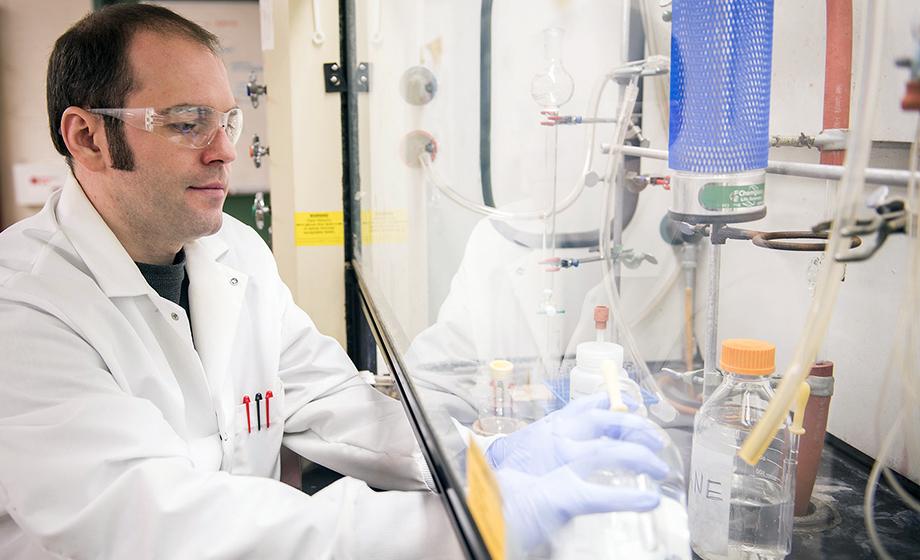

At Clark University, Michael Reardon (pictured), a doctoral candidate in chemistry, conducts research that could lead to better drugs to fight the spread of MRSA infections. He works in the laboratory of Charles Jakobsche, assistant professor in the Carlson School of Chemistry and Biochemistry.

“Drug-resistant bacteria are a serious problem, and we need to develop more methods to combat them. One of these methods is to make new drugs,” Reardon says. “Developing a synthetic route to a compound with good potency is the first step toward making a drug.”

To that end, Reardon’s project “has been to synthesize a compound produced in nature that has been found to effectively kill MRSA. While working toward this goal, we have developed new synthetic strategies and examined some unusual rates of chemical reaction.

“A synthetic route to make a natural product that kills MRSA,” he adds, “could potentially be used to discover compounds with better therapeutic properties and become an approved drug.”

A 2012 graduate in chemistry and biology from the Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts (MCLA), Reardon, now lives in Williamstown, Massachusetts. Below, he talks about his graduate experience at Clark.

Why did you choose Clark for graduate school?

Clark has the similar small school environment that I liked at MCLA. The research Professor Jakobsche was interested in was aligned with my interests. Clark is close enough to Springfield, where my fiancé was also in graduate school at the time.

What do you like best about being a graduate student at Clark?

I have had the privilege of mentoring some exceptional undergraduate students in my lab. Those that went on to graduate school have told me their experience in our lab has made them better scientists than the other first-year graduate students they work with.

Outside of your adviser, do you consider anyone else as a mentor?

Mark Turnbull is an exceptional professor who is passionate about learning and teaching others his wealth of knowledge. The way that I think critically about problems, the questions I ask my fellow researchers, and my approach to being a teaching assistant are all very much modeled after his example. If I become a professor, I will draw most of my teaching style from him.

Has anything you’ve discovered during your research particularly surprised or interested you?

You learn about trends in reactivity of certain molecules and there are lots of literature examples to show you how a particular type of reaction will work. There are always exceptions for a variety of reasons that may not always be apparent. Discerning why a “simple” reaction isn’t working can be an interesting task that can also broaden your understanding of how molecules interact and make you better at problem solving.

What do you hope to do after you graduate from Clark?

I am looking to teach and conduct research at undergraduate institutions close to where my fiancé and I live.

Can you talk about how your time at Clark has helped prepare you for your next endeavor?

Although it can be frustrating when things don’t work the way you think they will, two important skills can be obtained. One is learning how to take what you learned from the failures and propose a solution to the problem. The second is learning how to persevere through failure without loss of enthusiasm. I don’t think you can be a successful scientist without obtaining these two skills.